by editor | Sep 22, 2025 | Arts and Humanities, Environmental Literacy, Language Arts, Place-based Education

Staging Nature

Integrating Place-based Environmental Education, Literacy, and the Performing Arts

by Regine Randall, Rebecca Edmondson, and MaryAnne Young

“Teacher, teacher, teacher, teacher, teacher!”

Such a cry is likely to get any educator’s attention—and quickly. Yet, this repetitive call is not coming from a child but, rather, an ovenbird whose common breeding territory includes Acadia National Park in Maine. In a unique collaboration supported by a regional instructional grant, teachers Rebecca Edmondson and MaryAnne Young at Conners Emerson School in Bar Harbor, Maine—the primary gateway for Acadia—developed a musical to integrate multiple elements of the state’s Kindergarten–Grade 5 curriculum while also helping children to take notice of the very special place where they live.

Creating the musical Plant Kindness and Gather Love gave the students at Conners Emerson, as well as the communities on Mount Desert Island, an opportunity to celebrate the 2016 centennial of Acadia National Park and the bicentennial of Maine in 2020. Plant Kindness and Gather Love, however, was much more than that: it served as a much-needed model for creative teaching where learning objectives incorporate important foundational skills with efforts going well beyond screens or a brick and mortar building to raise children’s awareness of the world around them.

The seed of an idea takes root

Acadia National Park draws several million visitors from across the world every year. Yet, Edmondson and Young wondered how well students at Conners Emerson really knew what was in their own backyard? Having collaborated frequently and over time to blend language arts with music, Edmondson and Young observed that this integrated approach had a consistently positive impact on student learning and engagement. Young had a regular practice of sharing books with children in which the lyrics of a song were, in fact, the entire narrative of the story. With books in hand, the students then sought out Edmondson’s help in learning the songs. Singing the text breathed new life into traditional read-alouds. With this in mind, Edmondson realized that she and Young could adapt the same approach beyond a single book or skill (e.g. alphabet learning) to create an original story about Acadia. As noted earlier, the project coincided with celebrations of the centennial of Acadia and the bicentennial of Maine but also tapped into traditional academic subjects and literacy standards. Raising awareness of the park’s natural diversity through the musical was simply one more opportunity for Edmondson and Young to amplify what could be discovered within Acadia but also a chance to join with park associates in highlighting stewardship through family-friendly conservation practices.

Acadia National Park draws several million visitors from across the world every year. Yet, Edmondson and Young wondered how well students at Conners Emerson really knew what was in their own backyard? Having collaborated frequently and over time to blend language arts with music, Edmondson and Young observed that this integrated approach had a consistently positive impact on student learning and engagement. Young had a regular practice of sharing books with children in which the lyrics of a song were, in fact, the entire narrative of the story. With books in hand, the students then sought out Edmondson’s help in learning the songs. Singing the text breathed new life into traditional read-alouds. With this in mind, Edmondson realized that she and Young could adapt the same approach beyond a single book or skill (e.g. alphabet learning) to create an original story about Acadia. As noted earlier, the project coincided with celebrations of the centennial of Acadia and the bicentennial of Maine but also tapped into traditional academic subjects and literacy standards. Raising awareness of the park’s natural diversity through the musical was simply one more opportunity for Edmondson and Young to amplify what could be discovered within Acadia but also a chance to join with park associates in highlighting stewardship through family-friendly conservation practices.

Centuries ago, philosophers Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi and Friedrich Froebel argued that the best education occurred when children learned with the head, heart, and hands through play (McKenna, 2010; Tracey & Morrow 2012). Plant Kindness & Gather Love became a manifestation, quite literally, of Unfoldment Theory where teachers provided the necessary support for the children’s play (Prochner, 2021). Moreover, Edmondson and Young believed that such a musical would help children as young as kindergarten begin to see themselves as stewards of the earth because coming to love a place foments a desire to know and protect it (North American Association for Environmental Education [NAAEE], 2016). Despite the Herculean effort required to launch any school production, the excitement and pleasure embedded in this creative endeavor optimized learning for students and teachers alike while also forging a stronger and more memorable connection to the natural world. What makes the work unique is that their younger students did not need to wait until middle or high school to “envision knowledge” because this collaboration gave them the opportunity to be actors in sharing what they learned with a community that may or may not have known the same content (Langer, 2011).

From root to branch

Plant Kindness and Gather Love developed into a forty-minute musical with ten original songs written, arranged, and choreographed by Young and Edmondson with parts for fifteen characters. In the planning stage, Young and Edmondson brainstormed ideas for the musical with the Acadia National Park (ANP) Education Coordinator, Katie Petri, as well as other ANP associates. The Park Service went on to provide material support for the production in the form of Junior Ranger hats. The goal of the musical was to expand the venues through which children learned environmental content specific to Acadia and Mt. Desert Island. Instructional activities that supported the production of the musical ranged from students sketching and labeling wildflowers (where they also learned about the Fibonacci sequence) to discussing and illustrating the dramatic seasonal changes in Acadia to determining the components of stewardship and encouraging that we all act upon them. Such endeavors help introduce children, especially those in kindergarten and the primary grades, to all the park has to offer since more formal outdoor education programs (e.g., Young Birder, Schoodic Adventure) often begin a bit later, typically around age ten or fourth grade.

Plant Kindness and Gather Love developed into a forty-minute musical with ten original songs written, arranged, and choreographed by Young and Edmondson with parts for fifteen characters. In the planning stage, Young and Edmondson brainstormed ideas for the musical with the Acadia National Park (ANP) Education Coordinator, Katie Petri, as well as other ANP associates. The Park Service went on to provide material support for the production in the form of Junior Ranger hats. The goal of the musical was to expand the venues through which children learned environmental content specific to Acadia and Mt. Desert Island. Instructional activities that supported the production of the musical ranged from students sketching and labeling wildflowers (where they also learned about the Fibonacci sequence) to discussing and illustrating the dramatic seasonal changes in Acadia to determining the components of stewardship and encouraging that we all act upon them. Such endeavors help introduce children, especially those in kindergarten and the primary grades, to all the park has to offer since more formal outdoor education programs (e.g., Young Birder, Schoodic Adventure) often begin a bit later, typically around age ten or fourth grade.

Interest in the musical spread throughout the school and the larger community. Locally, the art teacher helped with scenery and displays, a local greenhouse donated flowering plants and foliage, and parents constructed costumes. To help other teachers throughout the state and New England consider similar projects, Petrie organized a teacher workshop at the Schoodic Institute at Acadia National Park based on Plant Kindness and Gather Love as a follow up to performances in Bar Harbor, Maine. Additional workshops on the musical were offered at the Maine Music Educators Association Conference and the Maine Environmental Education Association Conference. Most notably, a copy of Plant Kindness and Gather Love went to Washington DC to be placed on Senator Susan Collins’ reception room table along with other children’s books by Maine authors.

Making music

The songs within the musical Plant Kindness and Gather Love moved from broad concepts to specific ideas. In “Nature Lover,” the introduction began with a simple request: step outside. Jason Mraz had expressed this same sentiment years earlier in a clever rearrangement of his smash pop hit, “I’m Yours” where, during his performance of “Outdoors” on Sesame Street, he sings about the good feeling we get when we’re no longer “trapped between the walls and underneath the ceiling” (Sesame Street, 2009). Edmondson and Young took a similar approach by using song to inspire students to explore, but Acadia was the place to where children were taking a “close look or commanding view.” Only through experiencing the sights, feelings, sounds, and wanderings in a place like Acadia can they promote the desire, as Jason Mraz also reminded us, that “all of nature deserves to be loved, loved, loved, loved, loved” In the musical, a “nature lover” may be one who goes on to identify birds in Acadia by their unique calls or one who takes the initiative necessary to lead for an environmentally literate citizenry as made manifest by Maine’s motto of “Dirigo” (“I lead” or “I direct”).

The songs within the musical Plant Kindness and Gather Love moved from broad concepts to specific ideas. In “Nature Lover,” the introduction began with a simple request: step outside. Jason Mraz had expressed this same sentiment years earlier in a clever rearrangement of his smash pop hit, “I’m Yours” where, during his performance of “Outdoors” on Sesame Street, he sings about the good feeling we get when we’re no longer “trapped between the walls and underneath the ceiling” (Sesame Street, 2009). Edmondson and Young took a similar approach by using song to inspire students to explore, but Acadia was the place to where children were taking a “close look or commanding view.” Only through experiencing the sights, feelings, sounds, and wanderings in a place like Acadia can they promote the desire, as Jason Mraz also reminded us, that “all of nature deserves to be loved, loved, loved, loved, loved” In the musical, a “nature lover” may be one who goes on to identify birds in Acadia by their unique calls or one who takes the initiative necessary to lead for an environmentally literate citizenry as made manifest by Maine’s motto of “Dirigo” (“I lead” or “I direct”).

Thinking, seeing, listening, learning, dancing, singing

Plant Kindness and Gather Love integrated content to develop higher-order thinking skills in identification, comparison/contrast, mapping, synthesis, and representation. Typically, the focus on higher-order thinking characterizes learning objectives in grades six to twelve when basic academic skills are assumed to be more fully developed (Zwiers, 2004). Yet, as Johns and Lenski (2014) note, learning anything requires that we can recognize something for what it is and also know what it is not. Edmondson and Young capitalized on this principle in their musical. For instance, the tempo of the song “Beacon Bills” is allegro (brisk) and includes the calls of no less than ten birds found in the park. Children become acclimated to a “prima donna” cardinal calling “purty, purty, purty” whereas a chestnut-sided warbler is “pleased, pleased, pleased to meet cha.” What is significant here is that students come to know things not through sight or seatwork alone. They can also learn by seeing what gets left behind: tracks, nests, scents, even scat! Not actually seeing but still knowing is the essence of inferential reasoning.

Plant Kindness and Gather Love integrated content to develop higher-order thinking skills in identification, comparison/contrast, mapping, synthesis, and representation. Typically, the focus on higher-order thinking characterizes learning objectives in grades six to twelve when basic academic skills are assumed to be more fully developed (Zwiers, 2004). Yet, as Johns and Lenski (2014) note, learning anything requires that we can recognize something for what it is and also know what it is not. Edmondson and Young capitalized on this principle in their musical. For instance, the tempo of the song “Beacon Bills” is allegro (brisk) and includes the calls of no less than ten birds found in the park. Children become acclimated to a “prima donna” cardinal calling “purty, purty, purty” whereas a chestnut-sided warbler is “pleased, pleased, pleased to meet cha.” What is significant here is that students come to know things not through sight or seatwork alone. They can also learn by seeing what gets left behind: tracks, nests, scents, even scat! Not actually seeing but still knowing is the essence of inferential reasoning.

Another song in Plant Kindness and Gather Love has children singing of the wildflowers in Acadia. This scene incorporates movement because the children who play daisies, violets, bachelor buttons, British soldiers, foxgloves, and Johnny jump-ups are “dancing in the breeze” along the sea. Movement can solidify content in long-term memory, and we see this technique in teaching letters through air writing as well as during exercised where children tap out sounds or clap to count syllables (Madan & Singhal, 2012). That said, imagining that the wind off the Gulf of Maine made you sway in the same way as Queen Anne’s lace can fuse children’s personal expression with their connection to nature.

Children performing as flowers may be charming as well as kinesthetic, but it did not veil the very pointed message contained in the refrain. As the “flowers” came together in a true “kindergarten,” they sang out “Don’t pick me” over and over. Children’s growing sense of the natural world develops alongside their growing sense of themselves, as well as others, in the world. By leaving flowers to bloom and go to seed, we are making a promise to those who will come upon them in the next season that they play a vital role in the park ecosystem in addition to being a pleasure we share (Harlan & Rivkin, 2008). Of course, not all plants are equal, and such a song helps elementary science teachers also discuss the concepts of invasive species such as purple loosestrife in the park.

Children performing as flowers may be charming as well as kinesthetic, but it did not veil the very pointed message contained in the refrain. As the “flowers” came together in a true “kindergarten,” they sang out “Don’t pick me” over and over. Children’s growing sense of the natural world develops alongside their growing sense of themselves, as well as others, in the world. By leaving flowers to bloom and go to seed, we are making a promise to those who will come upon them in the next season that they play a vital role in the park ecosystem in addition to being a pleasure we share (Harlan & Rivkin, 2008). Of course, not all plants are equal, and such a song helps elementary science teachers also discuss the concepts of invasive species such as purple loosestrife in the park.

More on reading and writing Acadia

Too often and in many schools, reading and writing activities in the primary grades are taught as discrete skills that divorce them from other content (Gabriel, 2013). With science of reading initiatives, this practice may become even more entrenched with the focus on content area reading and writing not gaining momentum until upper elementary or middle school when curriculum more often reflects scheduling constraints, staffing, or building organization rather than a pedagogical decision (Fullan et al., 2018). Yet, the musical and what children learned about Acadia easily lead to a variety of literacy activities that keep nature and content learning at the fore. For example, children who are developing phonological awareness, an important precursor to skilled reading, can participate in activities where they see pictures of different birds (such as owl, seagull, chickadee), name the bird, and then stomp out the number of syllables they hear in the name. In a word identification lesson focusing on the onset (letter or letters making the initial consonant sound, blend, or digraph) and rime (the vowel that follows and remaining letters) of one syllable words, choosing a word from one of the songs (e.g., “pick” from the refrain “Don’t Pick Me!” in “Wildflowers of Acadia”) so that children can change the first letter(s) to form other words strongly supports decoding and spelling development (tick, quick, stick, chick, etc.). Since students are likely to have been introduced to this vocabulary, the words are easier to decode for two reasons: 1) they are within the same phonetic word family, and 2) they have become part of students’ receptive and expressive language used when learning about Acadia.

Too often and in many schools, reading and writing activities in the primary grades are taught as discrete skills that divorce them from other content (Gabriel, 2013). With science of reading initiatives, this practice may become even more entrenched with the focus on content area reading and writing not gaining momentum until upper elementary or middle school when curriculum more often reflects scheduling constraints, staffing, or building organization rather than a pedagogical decision (Fullan et al., 2018). Yet, the musical and what children learned about Acadia easily lead to a variety of literacy activities that keep nature and content learning at the fore. For example, children who are developing phonological awareness, an important precursor to skilled reading, can participate in activities where they see pictures of different birds (such as owl, seagull, chickadee), name the bird, and then stomp out the number of syllables they hear in the name. In a word identification lesson focusing on the onset (letter or letters making the initial consonant sound, blend, or digraph) and rime (the vowel that follows and remaining letters) of one syllable words, choosing a word from one of the songs (e.g., “pick” from the refrain “Don’t Pick Me!” in “Wildflowers of Acadia”) so that children can change the first letter(s) to form other words strongly supports decoding and spelling development (tick, quick, stick, chick, etc.). Since students are likely to have been introduced to this vocabulary, the words are easier to decode for two reasons: 1) they are within the same phonetic word family, and 2) they have become part of students’ receptive and expressive language used when learning about Acadia.

Such an activity moves from word and spelling patterns to an opportunity to record salient observations based on what happens in the park. For instance, “Tuck your pants into your socks to avoid tick bites.” Another might be “With a quick dive, a loon snatches a fish.” Or, “Adding a branch here and a little stick there, beavers keep their dam in good shape.” Finally, “Trails to Jordan, Valley Cove, and Precipice cliffs often close in the spring because peregrine falcons nest there and raise their chicks.” In another spin on word learning, the use of rhyming words such as tea, ski, and tree all contain different graphemes (ea, i, and ee) that are among the letter combinations that “spell” the long /e/ sound. Not only do such activities help children learn phonics concepts and other basic skills, but they are also introducing content specific vocabulary (loon, dam), homonyms (their, there), and usage based on context (nest as a verb). Bridging the observation skills that help children notice the macro and micro details within the natural world strengthens their ability to notice patterns and differences across multiple areas.

Speaking from my own perspective as a teacher educator, I welcome instruction that moves away from over-dependence on workbooks and commercial programs. Teachers who understand the scope and sequence of language development are poised to use any text any day to capitalize on how words work (sounds, spelling, syllables) and the ways we use words to create meaning and show what we know. Writing prompts that simply ask children to record what they see (the waves rolling in at Sand Beach), feel (wind at the top of Cadillac Mountain), or hear (the collision of water and air at Thunder Hole) are always authentic in the sense that responses can change day by day, hour by hour, or minute by minute. In terms of checking understanding of key facts or concepts, students can also complete sentence stems such as:

- Hiking in the woods means….(e.g. you might get bug bites).

- Being a park ranger means…(e.g. you have to be good with the public).

- Loving nature means…(e.g. you are happiest outside).

- Going to Acadia means…(e.g. you are on an island, or you could be on the Schoodic peninsula, or you are in a National Park).

Open-ended sentence stems allow children to generate many different responses with varying level of detail. Such responses can also suggest what we need to study further or better understand. It is a low-risk activity that introduces children to multiple perspectives while also enabling the teacher to identify misconceptions or misinformation (Randall & Marangell, 2018). Further, the sentence stems serve as a launch for extended writing on a self-selected topic of interest to the student. Ultimately, though, Plant Kindness and Gather Love went beyond interdisciplinary cross-pollination: it helped teachers understand how nature and place can re-energize lessons to improve targeted skills, expand our ideas of text to include multimodal materials beyond print (artifacts, audio, digital collections, etc.), and facilitate content learning. Historically, we know what engages learners and creates success; the joy and pleasure that went into imagining, producing, and performing Plant Kindness and Gather Love are the same emotions that motivate any learner to gain important skills, understand content more deeply, achieve more, and seek out new experiences wherever they are (Dewey, 1938; Duke et al., 2021; Gardner, 1999; Rosenblatt, 1938).

Show and share how to care

The musical concluded with an ode to the beauty of the park, which is undeniable and fine as far that goes, but also, more pointedly, with a call to be active in its preservation. The different songs, choreography, and even the costuming in the musical all contributed to creating the sense of wonder that comes from living in proximity to the natural world (Wilson, 1994). The score and lyrics for “Nature Lover” in Plant Kindness and Gather Love sets the stage by encouraging discovery, and the North American Association for Environmental Education (2016) described children as naturally inquisitive because “everything” is worth exploring “with all of the senses” (p. 2). So, exploring is for everyone but, perhaps, it is children’s particular ability to notice “a fish, a beaver, or an otter…a little bird…a white-tailed deer” that can reignite our own interest in using natural places as tableaux for learning.

The musical concluded with an ode to the beauty of the park, which is undeniable and fine as far that goes, but also, more pointedly, with a call to be active in its preservation. The different songs, choreography, and even the costuming in the musical all contributed to creating the sense of wonder that comes from living in proximity to the natural world (Wilson, 1994). The score and lyrics for “Nature Lover” in Plant Kindness and Gather Love sets the stage by encouraging discovery, and the North American Association for Environmental Education (2016) described children as naturally inquisitive because “everything” is worth exploring “with all of the senses” (p. 2). So, exploring is for everyone but, perhaps, it is children’s particular ability to notice “a fish, a beaver, or an otter…a little bird…a white-tailed deer” that can reignite our own interest in using natural places as tableaux for learning.

You, too, may live in an area that has of extraordinary natural beauty and diversity, is near a wonderful park, or, equally important, want to make wherever it is you do live more special in the eyes of children. For instance, Last Stop Market Street by Matt de la Pena and Christian Robinson is a children’s picture book of city life where Nana helps her grandson smell the rain, watch it pool on flower petals, and be a better witness to what’s beautiful in people, places, and things. With this in mind, the success of Plant Kindness and Gather Love may be just the right incentive for you and your colleagues to tell the “lively stories” – in any form, not just musicals – of the places and the inhabitants in your community (van Dooren, 2014).

References

Dewey, John. (1938). Experience and education. Macmillan.

Duke, N. K., Ward, A. E., & Pearson, P. D. (2021). The science of reading comprehension instruction. The Reading Teacher, 74(6), 663-672.

Fullan, M., Quinn, J., & McEachen, J. (2018). Deep learning: Engage the world, change the world. Corwin.

Gabriel, R. (2013). Reading’s non-negotiables: Element of effective reading instruction. Rowman & Littlefied Education.

Gardner, H. (1999). Intelligence reframed: Multiple intelligences for the twenty-first century. Basic Books.

Harlan, J. D., & Rivkin, M. S. (2008). Science experiences for the early childhood years: An integrated affective approach (9th ed.). Pearson.

Johns, J., & Lenski, S. (2014). Improving reading: Strategies, resources, and Common Core connections. Kendall-Hunt.

Langer, J. A. (2011). Envisioning knowledge: Building literacy in the academic disciplines. Teachers College.

Madan, C. R., & Singhal, A.. (2012). Using actions to enhance memory: Effects of enactment, gestures, and exercise on human memory. Frontiers in Psychology, 3(507): 1-4. http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00507

McKenna, M. K. (2010). Pestalozzi revisited: Hope and caution for modern education. Journal of Philosophy and History of Education, 60, 121-25.

North American Association for Environmental Education. (2016). Guidelines for excellence: Early childhood environmental education programs. NAAEE. https://cdn.naaee.org/sites/default/files/final_ecee_guidelines_from_chromographics_lo_res.pdf

Prochner, L. (2021). Our proud heritage. Take it outside; A history of nature-based education. NAEYC. https://www.naeyc.org/resources/pubs/yc/fall2021/take-it-outside

Randall, R., & Marangell, J. (2018). Changing the narrative: Literacy as sustaining practice in every classroom. Association of Middle Level Education, 6(2), 10-12. https://www.amle.org/BrowsebyTopic/WhatsNew/WNDet/TabId/270/ArtMID/888/ArticleID/918/Changing-the-Narrative.aspx

Rosenblatt, L. (1938). Literature as exploration. Appleton-Century.

Sesame Street. (2009, December 18). Outdoors with Jason Mraz [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZrqF7yD10Bo&ab_channel=SesameStreet

Tracey, D. H., & Morrow, L. M. (2012). Lenses on reading: An introduction to theories and models (2nd ed.). Guilford.

van Dooren, T. (2014). Flight ways. Columbia University Press.

Wilson, R. (1994). Environmental education at the early childhood level. North American Association for Environmental Education.

Zwiers, J. (2004). Developing academic thinking skills in grades 6–12: A handbook of multiple intelligence activities. International Reading Association.

Authors

Régine Randall, PhD, is a professor in Curriculum and Learning at Southern Connecticut State University (SCSU) in New Haven, Connecticut where she teaches both graduate and undergraduate courses in education. Her teaching and research interests allow for regional collaboration with K-12 educators on literacy instruction and assessment, student engagement, and best practices in environmental and agricultural education. With roots in Maine, Régine is an avid hiker and biker throughout New England and the Adirondack Mountains of upstate New York.

Régine Randall, PhD, is a professor in Curriculum and Learning at Southern Connecticut State University (SCSU) in New Haven, Connecticut where she teaches both graduate and undergraduate courses in education. Her teaching and research interests allow for regional collaboration with K-12 educators on literacy instruction and assessment, student engagement, and best practices in environmental and agricultural education. With roots in Maine, Régine is an avid hiker and biker throughout New England and the Adirondack Mountains of upstate New York.

Rebecca Edmondson is a composer, conductor, clinician who has taught in both public and private schools in Maine and Pennsylvania for the past forty years. Her school music program was one of 12 in the country designated as a Model Music Education Program, and her writing has appeared in the American String Teacher. In addition to winning composition competitions, Rebecca was named the 2022 Maine’s Hancock County Teacher of the Year. She continues to nurture the love of learning through music and developing children’s books. All this has prepared her to become Liam and Finn’s Grammy.

Rebecca Edmondson is a composer, conductor, clinician who has taught in both public and private schools in Maine and Pennsylvania for the past forty years. Her school music program was one of 12 in the country designated as a Model Music Education Program, and her writing has appeared in the American String Teacher. In addition to winning composition competitions, Rebecca was named the 2022 Maine’s Hancock County Teacher of the Year. She continues to nurture the love of learning through music and developing children’s books. All this has prepared her to become Liam and Finn’s Grammy.

MaryAnne Young is a lifetime resident of coastal Maine. She comes from a large family tree of educators and authors. After more than 38 years as an educator MaryAnne retired from Conners Emerson School. She engages with young learners as a substitute teacher and continues to write poetry and story songs. MaryAnne is inspired by the woods, waters and wildlife that surround the place she calls home. Her most joyful lifetime achievement is being a proud Mimi to Cameron and Maya…the new generation of Nature Lovers!A

MaryAnne Young is a lifetime resident of coastal Maine. She comes from a large family tree of educators and authors. After more than 38 years as an educator MaryAnne retired from Conners Emerson School. She engages with young learners as a substitute teacher and continues to write poetry and story songs. MaryAnne is inspired by the woods, waters and wildlife that surround the place she calls home. Her most joyful lifetime achievement is being a proud Mimi to Cameron and Maya…the new generation of Nature Lovers!A

by editor | Sep 12, 2025 | Environmental Literacy, Inquiry, Language Arts, Learning Theory, Teaching Science

The wild turkeys on my street don’t wear booties in the winter and the mouse in my house doesn’t wear bonnets from a closet! Should environmental education start with realism in the early years?

by Suzanne Major Ph.D.

Anthropology of Early Childhood Education

Books and movies have made animals, insects and plants so charming and sympathetic, and at times so frightfully magnificent and impressive. Can young children do without these entertaining animations and anthropomorphism, that is, making animals, insects and plants look and behave like humans? Do we dress them up, make them talk and have them drink tea from porcelain cups because we don’t know anything about them? Or do we think that young children can’t appreciate them for what they are? Young children across the world easily demonstrate that they are capable of perceiving, observing and remembering the descriptive elements belonging to an animal, a plant or insect. They can collect information and draw knowledge from it. My friend Omar in Cairo, three years old, knows not to treat the wild dogs as pets if only, because they are infested with fleas. My neighbour Maddy learned at two-years-old not to bother the bees in the hive hanging from the apple tree. Jenny, in Moncton New Brunswick, four years old, can identify the leaves of poison ivy in the forest and knows to wear long pants to protect her legs when she goes for walks with her family. Children learn very early on what is dangerous or not, comestible or not, pleasant or disagreeable. They are also capable of attaching symbolic value to things. Children everywhere offer flowers to their mothers and grandmothers to express their feelings or to create a nice event! As you know, they learn using observation, imitation, repetition or as Piaget wrote “perception, assimilation and accommodation”. They also identify with the knowledge of others or the information offered by nature. They encode it just because others use it, or they happened to observe it. They sometimes need information quickly, so they identify with the information others have, to fill the gap until they can adapt or replace it with more personal information. Through a very individualistic process of thought creation they retain or ignore elements of information and knowledge. They set the ones they favour in memory and replay others in thought, all sorts of ways assessing what works or not.

Finding animals, insects, plants or things cute, vulnerable or charming stems from the capability of empathy which is more difficult to use for what is ugly, threatening or disgusting. This notion of finding things cute is a cultural one that is cultivated and exploited by stories, books, animations and movies. Empathy is used to ensure survival among our own and can be transferred to animals, insects and plants. But it also allows sentiments to emerge that can be directed, intentions that can be instructed and behaviours that can be modelled. It is often used because of marketing interests but it can also serve pedagogically to create empathy. “Charlotte, the spider” is a good example!

The question here is do we need to create stories to nurture environmental education with children? Are we trying to sell them nature? Do we need to manipulate them towards environmental education or can we let them acquire a more significant first-hand experience? Should we not have a more functional approach about how everything has a place and time and is part of a balance of all and everything in the universe? Should we not let nature imprint itself on children, so they can sense by themselves their place on earth? Is that not fascinating enough? Let’s take the booties and the bonnets off the turkeys and the mice on these pages to see where this can go! Pink and white mice are mammals of the order of Rodentia and the genus MUS.[1] Wikipedia tells us that they are climbers, jumpers and swimmers and have lots of energy. They use their tail for tripoding so they can observe, listen and feel their environment. They can sense surface and air movements with their whiskers and use pheromones for communication. It is difficult for them to survive away from human settlements and in our houses, they actually become domesticated! They eat plant matter or anything else they can get their paws on. They will even eat their own feces for nutrients produced by intestinal bacteria. They are great at reproducing. They have a 19 to 21 days gestation, have 3 to 14 pups and 5 to 10 litters a year and females are sexually mature at 6 weeks. Do the math! We like them outside in the fields and not in our houses. Where I live, coyotes can hear and smell them and eagerly feast on them. Small falcons and owls can see them easily and pick them up in a flash. Last summer was very warm and wet. The vegetation exploded as well as the mice population. As I walked in my garden, they would jump up right and left to move away from me.

What can we infer from this information for environmental education? Young children spontaneously sit on their legs, hold up their bent hands and wiggle their noses to imitate mice. By observing mice and comparing their bodies with them, young children can engage in an array of locomotive and motor activities. Experimenting with sensing surfaces and air movements with their skin and their hair they can discover how this gives them information and knowledge. They can explore and sense space with the whole body like the security of a small shelter and the unsettling feeling of wide-open spaces. Discovering smells and odours for two and three-year- olds can be a lot of fun and for older children, linking those to chemical reactions can awake them to science. Seeking the mice out in the fields can be very interesting as they make little tunnels that go everywhere under the snow and through the dried grass. Reflecting with young children over three years old on the mice population in relation to the weather and the consequences this brings is interesting because the phenomenon attracts coyotes near houses which creates a real threat to house pets and small farm animals.

Let’s consider wild turkeys or Meleagris Gallopavo. Wikipedia informs us that the females are called hens and the males are known as toms. The males have huge tails they fan out to attract the females and impress the other males. They have up to 6,000 feathers and they can fly for 400 metres. To protect themselves from storms, they can roost up to 16 metres above ground in tall conifers. They gobble and emit a low-pitched drumming sound. If cornered, they can be aggressive towards humans. They are omnivores but prefer nuts, seeds and berries. They will eat amphibians, snakes and reptiles. Their babies are called poults. The hens lay 10 to 14 eggs and incubate for 28 days and the little ones are ready to go 12 to 24 hours after hatching. They can fall prey to coyotes, grey wolfs, lynxes and foxes.

The adults are around four feet tall and the big males can weigh some 37 pounds. I observe them regularly around my house. Hens flock together with the young ones, 12 or 14 together as they walk around the fields and woods. When they cross the road, one leads on and at least one or two stay behind to gather everyone. They are very attentive, looking right and left and right again. One might even stand guard in the middle of the street to make sure everyone has crossed. I am told they made a comeback in recent years as they had disappeared because of over hunting. At night in the summer, when there is a storm, we can hear them gobble after each clap of thunder.

What can we infer from this information for environmental education? It’s a magnificent bird when it struts around displaying its beautiful black tail, but I reckon a young child would be impressed even afraid if it came face to face with a tom or a hen on the street or in the back yard. It certainly offers the opportunity to acquire new vocabulary with the wattle or snood hanging from its beak, the caruncles pending from its neck, its hairless head crown and beard or beards on a single bird, the spurs on the back of its legs and the three long toes on its feet. Two and three- year-olds would delight in knowing by heart the body parts of the wild turkey and comparing it with the ones of a chicken. Young children would also be impressed to measure themselves against the life-size drawing of a male turkey. Three and four-year-olds could explore what low-pitch drumming sounds are and could discuss why the turkeys gobble after the clap of thunder and even do a little research. As an educator, I would not miss the chance to make a parallel between the turkeys looking right and left and right again before crossing the street and children attempting to do the same but unable to fly away from danger! Finally, with older children it would be interesting to place the mice, the turkeys and the coyotes in their environment and talk about the relation between them.

Nature provides real and fascinating animations all by herself and children can appreciate the reality of animals, insects and plants. All sorts of elements can create the desire for observation and exploration. Exploration calls on focus which brings attention to details which creates in turn the need for manipulation. Manipulation and/or representation will lead to curiosity for functions which is knowledge. Knowledge for young children establishes the feeling of competence. Competence cultivates initiatives and permits the experience of trials and successes. In turn, the need and the pleasure for demonstration can take place, then patience to practice, to persist and develop skills becomes a reality. Later, mastering will open the cognitive door to metaknowledge.

Observation, exploration, focus, manipulation, representation, curiosity, knowledge, competence, initiative, demonstration, patience, mastering, metaknowledge, is a pedagogical sequence that young children can start experiencing when they are just a few months old.

Suzanne Major is an anthropologist and early childhood educator. She received her Ph. D. in 2015, with mention of excellence, in Anthropology of Early Childhood Education from the University of Montreal, Quebec, Canada. She also has a master’s degree in Child Studies which was obtained in 2004 at Concordia University, in Montreal, Canada. She has worked 12 years as Director for the Early Childhood Studies Program of the University of Montreal’s Faculty of Permanent Education.

Suzanne Major is an anthropologist and early childhood educator. She received her Ph. D. in 2015, with mention of excellence, in Anthropology of Early Childhood Education from the University of Montreal, Quebec, Canada. She also has a master’s degree in Child Studies which was obtained in 2004 at Concordia University, in Montreal, Canada. She has worked 12 years as Director for the Early Childhood Studies Program of the University of Montreal’s Faculty of Permanent Education.

by editor | Sep 7, 2025 | Critical Thinking, Environmental Literacy, Experiential Learning, Integrating EE in the Curriculum, K-12 Activities, Language Arts, Learning Theory

by Jim McDonald

The demands on classroom teachers to address a variety of different subjects during the day means that some things just get left out of the curriculum. Many schools have adopted an instructional approach with supports for students that teach reading and math, with the addition of interventions to teach literacy and numeracy skills which take up more time in the instructional schedule. In some of the schools that I work with there is an additional 30 minutes a day for reading intervention plus 30 more minutes for math intervention. So, we are left with the question, how do I fit time for science or environmental education into my busy teaching schedule?

In a recent STEM Teaching tools brief on integration of science at the elementary level, it was put this way:

We do not live in disciplinary silos so why do we ask children to learn in that manner? All science learning is a cultural accomplishment and can provide the relevance or phenomena that connects to student interests and identities. This often intersects with multiple content areas. Young children are naturally curious and come to school ready to learn science. Leading with science leverages students’ natural curiosity and builds strong knowledge-bases in other content areas. Science has taken a backseat to ELA and mathematics for more than twenty years. Integration among the content areas assures that science is given priority in the elementary educational experience (STEM Teaching Tool No. 62).

Why does this matter? Educators at all levels should be aware of educational standards across subjects and be able to make meaningful connections across the content disciplines in their teaching. Building administrators look for elementary teachers to address content standards in math, science, social studies, literacy/English Language arts at a minimum plus possibly physical education, art, and music. What follows are some things that elementary teachers should consider when attempting integration of science and environmental education with other subjects.

Things to Consider for Integration

The integration of science and environmental education concepts with other subjects must be meaningful to students and connect in obvious ways to other content areas. The world is interdisciplinary while the experience for students and teachers is often disciplinary. Learning takes place both inside and outside of school. Investigations that take place outside of school are driven by people’s curiosity and play and often cut across disciplinary subjects. However, learning in school is often fragmented into different subject matter silos.

Math and reading instruction dominate the daily teaching schedule for a teacher because that is what is evaluated on standardized tests. However, subjects other than ELA and math should be kept in mind when considering integration. Social studies and the arts provide some excellent opportunities for the integration of science with other content areas. In the NGSS, the use of crosscutting concepts support students in making sense of phenomena across science disciplines and can be used to prompt student thinking. They can serve as a vehicle for teachers to see connections to the rest of their curriculum, particularly English/Language Arts and math. Crosscutting concepts are essential tools for teaching and learning science because students can understand the natural world by using crosscutting concepts to make sense of phenomena across the science disciplines. As students move from one core idea to another core idea within a class or across grade-levels, they can continually utilize the crosscutting concepts as consistent cognitive constructs for engaging in sense-making when presented with novel, natural phenomena. Natural phenomena are observable events that occur in the universe and we can use our science knowledge to explain or predict phenomena (i.e., water condensing on a glass, strong winds preceding a rainstorm, a copper penny turning green, snakes shedding their skin) (Achieve, 2016).

Reading

Generally, when I hear about science and literacy, it involves helping students comprehend their science textbook or other science reading. It is a series of strategies from the field of literacy that educators can apply in a science context. For example, teachers could ask students to do a “close reading” of a text, pulling out specific vocabulary, key ideas, and answers to text-based questions. Or, a teacher might pre-teach vocabulary, and have students write the words in sentences and draw pictures illustrating those words. Perhaps students provide one another feedback on the effectiveness of a presentation. Did you speak clearly and emphasize a few main points? Did you have good eye contact? Generally, these strategies are useful, but they’re not science specific. They could be applied to any disciplinary context. These types of strategies are often mislabeled as “disciplinary literacy.” I would advocate they are not. Disciplinary literacy is not just a new name for reading in a content area.

Scientists have a unique way of working with text and communicating ideas. They read an article or watch a video with a particular lens and a particular way of thinking about the material. Engaging with disciplinary literacy in science means approaching or creating a text with that lens. Notably, the text is not just a book. The Wisconsin DPI defines text as any communication, spoken, written, or visual, involving language. Reading like a scientist is different from having strategies to comprehend a complex text, and the texts involved have unique characteristics. Further, if students themselves are writing like scientists, their own texts can become the scientific texts that they collaboratively interact with and revise over time. In sum, disciplinary literacy in science is the confluence of science content knowledge, experience, and skills, merged with the ability to read, write, listen, and speak, in order to effectively communicate about scientific phenomena.

As a disciplinary literacy task in a classroom, students might be asked to write an effective lab report or decipher the appropriateness of a methodology explained in a scientific article. They might listen to audio clips, describing with evidence how one bird’s “song” differs throughout a day. Or, they could present a brief description of an investigation they are conducting in order to receive feedback from peers.

Social Studies

You can find time to teach science and environmental education and integrate it with social studies by following a few key ideas. You can teach science and social studies instead of doing writer’s workshop, choose science and social studies books for guided reading groups, and make science and social studies texts available in your classroom library.

Teach Science/Social Studies in Lieu of Writer’s Workshop: You will only need to do this one, maybe two days each week. Like most teachers, I experienced the problem of not having time to “do it all” during my first year in the classroom. My literacy coach at the time said that writer’s workshop only needs to be done three times each week, and you can conduct science or social studies lessons during that block one or two times a week. This was eye-opening, and I have followed this guidance ever since. My current principal also encouraged teachers to do science and social studies “labs” once a week during writing time! Being able to teach science or social studies during writing essentially opens up one or two additional hours each week to teach content! It is also a perfect time to do those activities that definitely take longer than 30 minutes: science experiments, research, engagement in group projects, and so forth. Although it is not the “official” writers workshop writing process, there is still significant writing involved. Science writing includes recording observations and data, writing steps to a procedure/experiment, and writing conclusions and any new information learned. “Social studies writing” includes taking research notes, writing reports, or writing new information learned in a social studies notebook. Students will absolutely still be writing every day.

Choose Science and Social Studies Texts for Guided Reading Groups: This suggestion is a great opportunity to creatively incorporate science and social studies in your weekly schedule. When planning and implementing guided reading groups, strategically pick science and social studies texts that align to your current unit of study throughout the school year. During this time, students in your guided reading groups can have yet another opportunity to absorb content while practicing reading strategies.

Make Science and Social Studies Texts Available and Accessible in Your Classroom Library: During each unit, select texts and have “thematic unit” book bins accessible to your students in a way that is best suited for your classroom setup. Display them in a special place your students know to visit when looking for books to read. When kids “book-shop” and choose their just-right books for independent reading, encourage them to pick one or two books from the “thematic unit” bin. They can read these books during independent reading time and be exposed to science and social studies content.

Elementary Integration Ideas

Kindergarten: In a kindergarten classroom, a teacher puts a stuffed animal on a rolling chair in front of the room. The teacher asks, “How could we make ‘Stuffy’ move? Share an idea with a partner”. She then circulates to hear student talk. She randomly asks a few students to describe and demonstrate their method. As students share their method, she will be pointing out terms they use, particularly highlighting or prompting the terms “push” and “pull”. Next, she has students write in their science notebooks, “A force is a push or a pull”. This writing may be scaffolded by having some students just trace these words on a worksheet glued into the notebook. Above that writing, she asks students to draw a picture of their idea, or another pair’s idea, for how to move the animal. Some student pairs that have not shared yet are then given the opportunity to share and explain their drawing. Students are specifically asked to explain, “What is causing the force in your picture?”.

For homework, students are asked to somehow show their parents a push and a pull and tell them that a push or a pull is a force. For accountability, parents could help students write or draw about what they did, or students would just know they would have to share the next day.

In class the next day, the teacher asks students to share some of the pushes and pulls they showed their parents, asking them to use the word force. She then asks students to talk with their partner about, “Why did the animal in the chair sometimes move far and sometimes not move as far when we added a force?”. She then asks some students to demonstrate and describe an idea for making the animal/chair farther or less far; ideally, students will push or pull with varying degrees of force. Students are then asked to write in their notebooks, “A big force makes it move more!” With a teacher example, as needed, they also draw an image of what this might look like.

As a possible extension: how would a scientist decide for sure which went further? How would she measure it? The class could discuss and perform different means for measurement, standard and nonstandard.

Fourth Grade Unit on Natural Resources: This was a unit completed by one group of preservice teachers for one of my classes. The four future elementary teachers worked closely in their interdisciplinary courses to design an integrated unit for a fourth-grade classroom of students. The teachers were given one social studies and one science standard to build the unit around. The team of teachers then collaborated and designed four lessons that would eventually be taught in a series of four sessions with the students. This unit worked to seamlessly integrate social studies, English language arts, math, and science standards for a fourth-grade classroom. Each future teacher took one lesson and chose a foundation subject to build their lesson upon. The first lesson was heavily based on social studies and set the stage for the future lessons as it covered the key vocabulary words and content such as nonrenewable and renewable resources. Following that, students were taught a lesson largely based on mathematics to better understand what the human carbon footprint is. The third lesson took the form of an interactive science experiment so students could see the impact of pollution on a lake, while the fourth lesson concluded with an emphasis on language arts to engage students in the creation of inventions to prevent pollution in the future and conserve the earth’s resources. Contrary to the future educators’ initial thoughts, integrating the various subject areas into one lesson came much more easily than expected! Overall, they felt that their lessons were more engaging than a single subject lesson and observed their students making connections on their own from previously taught lessons and different content areas.

References

Achieve. (2016). Using phenomena in NGSS-designed lessons and units. Retrieved from https://www.nextgenscience.org/sites/default/files/Using%20Phenomena%20in%20NGSS.pdf

Hill, L., Baker, A., Schrauben, M. & Petersen, A. (October 2019). What does subject matter integration look like in instruction? Including science is key! Institute for Science + Math Education. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Retrieved from: http://stemteachingtools.org/brief/62

Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction. (n.d.) Clarifying literacy in science. Retrieved from: https://dpi.wi.gov/science/disciplinary-literacy/types-of-literacy

Jim McDonald is a Professor of Science Education at Central Michigan University in Mt. Pleasant, Michigan. He teaches both preservice teachers and graduate students at CMU. He is a certified facilitator for Project WILD, Project WET, and Project Learning Tree. He is the Past President of the Council for Elementary Science International, the elementary affiliate of the National Science Teaching Association.

Jim McDonald is a Professor of Science Education at Central Michigan University in Mt. Pleasant, Michigan. He teaches both preservice teachers and graduate students at CMU. He is a certified facilitator for Project WILD, Project WET, and Project Learning Tree. He is the Past President of the Council for Elementary Science International, the elementary affiliate of the National Science Teaching Association.

by editor | Sep 1, 2025 | At-risk Youth, Climate Change & Energy, Equity and Inclusion, Indigenous Peoples & Traditional Ecological Knowledge, Language Arts

First-person narratives bring climate change closer to home.

By Lauren G. McClanahan

“So, is her house actually sinking?”

“Yes, Heather, it is.”

“But, that’s so sad! I want to do something about that!”

No doubt my preservice secondary education student, Heather, is familiar with the topic of climate change. Everywhere we look, we see media coverage. But there still seems to be something missing. There still appears to be a disconnect, for my preservice teachers, anyway, between what they read about online and what they see in their day-to-day lives. And this has huge implications for their futures as public school teachers. One way to address this disconnect has been to put a face to the topic of climate change. By connecting all of my “Heathers” to students who live in places where climate change is having actual, observable effects, a topic that was once only theoretical to many of my students becomes real.

Kwigillingok, Alaska, vs. Bellingham, Wash.

My teacher-ed students at Western Washington University in Bellingham, Wash., come from multiple walks of life, are at different points in their educational and working careers, and have different goals for their futures as middle and high school teachers. However, one commonality that my students tend to share is their geography. Most hail from western Washington state—up and down the “I-5” corridor. Take the freeway north, and in 15 minutes, you’re in Canada. A few hours south, and you’ve crossed into Oregon. On a daily basis, my students don’t give much thought to climate change. No doubt, many claim to be “green” through-and-through. They recycle, use compact fluorescent bulbs, and buy local whenever possible. And these efforts are important; but as for the big changes—the catastrophic ones happening in our circumpolar regions—my students just don’t see it. In contrast, the students of Kwigillingok, Alaska, see these changes every day and can document firsthand how their village is changing because of them.

Kwigillingok is a small Yup’ik fishing village in western Alaska that sits along the Bering Sea. With a population of about 400, the residents depend on a subsistence culture to survive, much as they have done for thousands of years. Fishing, hunting, and creating and selling crafts are as integral today as they have been for centuries. However, our warming earth is now threatening that culture.

I began working with the students of “Kwig” several years ago, when one of my former students was hired to teach in the Lower Kuskokwim School District. What started as a simple pen-pal relationship between her high school students and my college students slowly transformed into the project described here. And while the students have changed over the years, the questions that they were asking of one another became more focused, until we decided that the topic of climate change was the main issue that everyone wanted to discuss.

The biggest challenge faced by the residents of Kwig is the melting of the permafrost, that layer of frozen ground that lies just below the earth’s surface and that is supposed to stay frozen year-round. Recently, that permafrost has begun to melt, and as a result, major changes are taking place. Many homes and other structures in the village are beginning to sink, leaning to one side as the permafrost they were built upon begins to shift. In addition to sinking homes, new, invasive species of plants are beginning to take root and grow, which in turn is slowly changing the migratory patterns of big game such as the local musk ox populations. Fishing, too, has been affected by the warming trend, and fish camps have had to relocate depending on the changing location of the fish. These are big changes that can be seen and felt and experienced daily in the lives of Kwig’s high school students. It was these changes that they wanted to tell us about, to tell the future teachers “down there” to share with all of their future students. They wanted to let everyone know that climate change is real and has a face and a name—hence the “First Person Singular” project. This was a project to create a warning for the rest of us, those of us who do not have to prop our houses up with sandbags or who do not have to go hungry due to a lack of fish in our rivers. Or at least not yet.

The “First Person Singular” Project

As mentioned, the relationship between Kwig and WWU began when a former student of mine was hired into the district. I had always been interested in Native cultures and found this to be an opportunity to weave that interest into the literacy classes that I teach. The more the students shared with us about their culture and their harsh, yet beautiful landscape, the more I felt as if I had to visit. In an initial visit, I met with the teachers and students at several village schools. I saw firsthand what the students of this region had to share with my students, not only from a cultural perspective, but also a scientific one as we delved deeper into the issue of climate change and its effect on their culture.

Recently, one of my current students approached me about completing his student teaching internship at the Kwig school. “I just want a very rural, very challenging school setting,” he told me. Well, did I have the place for him! Luckily, my intrepid student would not mind hauling his own water, which is what he would have to do, since many of the buildings in Kwig have no running water. He did, however, have the luxury of a newly installed incinerator toilet in his cabin—preferable to a Honey Bucket. Before he left, my student (a future English teacher) and I had talked about doing a project with his students that would combine disciplines and allow the students’ own voices to be heard. The concept of place-based education, of focusing curriculum on local issues, had been an important part of our university classes, and my student wanted to try it out. He liked the combination of using the local setting as the classroom, and letting his students “direct” their learning—two of the main components of place-based education. So, with his students’ input, a project was decided upon, and I made plans to come up and help facilitate the project after he eased into his new role as student teacher. I figured that another visit would give me an opportunity not only to formally observe my student teacher, but also work in person with this project and these students that I had been thinking about for some time.

Before I traveled to Kwig for the second time, I asked the high school students (with whom I communicated by email) to photograph any evidence of climate change that they could see in their village. Then, once I arrived, my student teacher and I sat down with each student to talk about the photos they had taken. This technique of using “auto-driven photo elicitation” (as it is called in the field of visual studies) proved to be beneficial. Auto-driven photo elicitation is simply when people involved in a research study take their own photographs, and use those photos as the basis for later interviews (Clark, 1999). The photos gave us a starting point—something on which to focus our conversation. Otherwise, I was afraid that the conversation might become too abstract, or even too uncomfortable (seeing as how the students had never met me face-to-face, but only through email). However, by focusing on the photos, we were able to get to the heart of what was important to the students. After all, we were talking about their photos, of evidence of climate change in their village.

After we spent time talking about the photos (individually and as a group), I asked students to pick a favorite photo and write about why it was the best choice to illustrate the effects of climate change. Because we had talked about the photos first, the writing part was easy. They could describe, in detail, why their photos mattered, and why their audience, my preservice teachers, needed to know about them. Then, after they had written their paragraphs, I asked students to read their paragraphs (or parts of their paragraphs) into a digital voice recorder so that we could incorporate their own voices (literally) into our final product. One of the students even volunteered to play the piano so that our project would have a soundtrack.

One of the students photographed a leaning building. He described it this way:

“The world is changing. It’s getting warmer and warmer. Ice is melting everywhere, even underground. The melting of the permafrost causes hills, houses, and other buildings to sink. Permafrost is a section in the ground where everything is frozen. It melts and refreezes around the year, but lately, there has been more melt than freeze. If we don’t do something, we could lose this beautiful land that we lived in for thousands of years, forever.”

He then wrote the same paragraph in his native Yup’ik language, and read them both aloud. This was powerful. Another student photographed seagulls that were hanging around later in the season than usual. She explained that “it’s unusual for them to still be here [in October], which suggests that [the ground] is not as cold as it looks.

He then wrote the same paragraph in his native Yup’ik language, and read them both aloud. This was powerful. Another student photographed seagulls that were hanging around later in the season than usual. She explained that “it’s unusual for them to still be here [in October], which suggests that [the ground] is not as cold as it looks.

Once the paragraphs had been written and recorded, students responded to several prompts that they created themselves, such as, “What is worth preserving in Kwig?” One student responded, “We don’t have a lot of money. We need to stay near the ocean so we can fish. We don’t want to have to move farther and farther back every few years. We can’t leave, but we can’t stay, either.” When asked what message they wanted to send to the preservice teachers in Washington, one student said, “Please understand that what you do down there has a great impact on us up here. Understand that we’re all in this together. Climate change doesn’t just affect polar bears—it affects people, too.”

The project’s final phase was to put our photos, words, and voices into a very short iMovie. The students helped plan the sequencing, and then we put it together. And while the “film” was only four and a half minutes long, it sent a strong message to the preservice teachers it was meant to educate. After viewing the movie, one of my preservice teachers wrote, “Now that I know this—now that I have seen these kids’ faces and heard their stories—I can’t ‘un-know’ it. Now I have to decide what I can do about it, both in my classroom, and in my everyday life.”

Larger Implications

Place-based education, while not a new concept, is particularly well-suited for the inclusion of student voices. With its aim of grounding learning in local phenomena and students’ lived experience (Smith, 2002), it can be easily adapted to fit any number of school curricula. For example, nearly every city or town has local issues that can be studied in greater depth, be they environmental issues (toxic wastewater), social justice issues (migrant workers’ access to health care), or issues dealing with the economy (how city taxes are used to fund local schools). In the case of our project, climate change was an obvious topic for exploration, given our fortunate connection with students in the far North. Plus, the topic fits nicely into the definition of “sustainability education.” Within WWU’s Woodring College of Education, our underlying assumption is that education for sustainability (as opposed to education about sustainability) will result in citizens who are more likely to engage in personal behavior or contribute to public policy decisions in the best interest of the environmental commons and future generations (Nolet, 2009).

Personal Implications

When students take control of their learning, and take control of how that learning can be demonstrated, amazing things can happen. For the Kwig high school students, they learned that they had not only some very important things to say, but also an audience that was receptive to and respectful of their words and ideas. For my preservice teachers, they learned that they are not the experts on everything, and sometimes they have to step aside to let the experts step forward (in this case, the students themselves). This idea of relinquishing power in the classroom can intimidate a new teacher, but it is an important lesson, especially regarding student engagement.

After viewing the high school students’ film, my preservice teachers had a lot to say about place-based education, and how this project connects students to their local communities, and society as a whole. One student commented, “Obviously, the kids in the movie care about what is happening to their homes and land. We need that heart in schools, or what they are learning means nothing.”

Many students also commented on the topic of climate change. “Now I know why I take the time to recycle! It’s not much, but it’s a small step I can take to help preserve the world’s cultures.” Another student said, “Now that I know this—about the challenges facing Kwig due to climate change—I feel obligated to do something about it.” Climate change now has a name and a face. It’s personal.

Similar projects that focus on topics of local concern could be created within other curricula. Any place-based study could benefit from hearing the voices of those most affected. Travel to each place is certainly not mandatory. Using even simple technology such as email or Skype could connect classrooms across town or across the world. Because, in the end, it is all about the relationships that can be forged as a result of storytelling. The more we know about others through their stories, in their own voices, the more inspired we might be to recognize those voices in our own.

References

Clark, C. (1999). The autodriven interview: A photographic viewfinder into children’s experience. Visual Sociology, 14, 39-50.

Nolet, V. W. (2009). Preparing sustainably literate teachers.Teachers College Record, 111(5).

Smith, G. A. (2002). Place-based education: Learning to be where we are. Phi Delta Kappan (April), 584-594.

Lauren G. McClanahan (Lauren.mcclanahan@wwu.edu) is a professor at Western Washington University in Bellingham, Wash.

by editor | Aug 26, 2025 | Arts and Humanities, At-risk Youth, Environmental Literacy, Language Arts

By Emilie Lygren

I am a poet and outdoor science educator.” This is what I say when asked what I do for work. For me, poetry and outdoor science are complementary ways of looking at the world. They’re both rooted in common attitudes of attention, curiosity, and humility. They both require being present with the world in a deep way. And both fields of study can support learners, educators, and communities to develop environmental literacy and a sense of place.

My own relationship with poetry and outdoor learning started early. While growing up in the Monterey area in California, I loved spending time outside. I liked to study nearby trees, plants, animals, and bodies of water, and I often composed poems in my mind based on what I saw. Paying close attention to my surroundings helped me feel grounded and connected to place. Learning through my own observations made me curious to know more. In part, these interests emerged from having access to outdoor spaces and parents who encouraged me to express myself creatively. I was also fortunate to learn through an ecosystem of experiences in nature and generous individuals and groups I’d known.

I had a fantastic sixth-grade science teacher who invited students to engage in curious, careful investigation of the mysteries of the world. At the beginning of a class period, he’d hand out binoculars and field guides, then say, “Go out and find out what birds we have on campus. Come back in an hour and tell me what you saw.” Throughout the school year, our class mapped which plants grew around the schoolyard, collected and sketched insects, searched for fence lizards, and discussed how the school’s water use impacted nearby animal and human communities. By the end of the year, I’d gained a set of tools and mindsets for nature study that continues to sustain me to this day; environmental education made a difference in how I perceived myself as a learner and as a community member.

But not everyone has the access to the outdoor spaces and environmental learning opportunities that I did. In fact, access to green space and educational opportunities is often stratified by race and class. Many organizations in California and beyond are working to address these disparities and expand access and inclusion in the outdoors, including affinity-based organizations like Latino Outdoors and Outdoor Afro, education and advocacy organizations like Justice Outside, networking and community-building organizations like Ten Strands, and many more. Policy efforts such as “A Blueprint for Environmental Literacy” lay out a vision and strategies for “educating every California student in, about, and for the environment.” And there are hundreds of providers across the state that offer outdoor learning experiences. The work of all of these organizations is important and necessary to support environmental literacy.

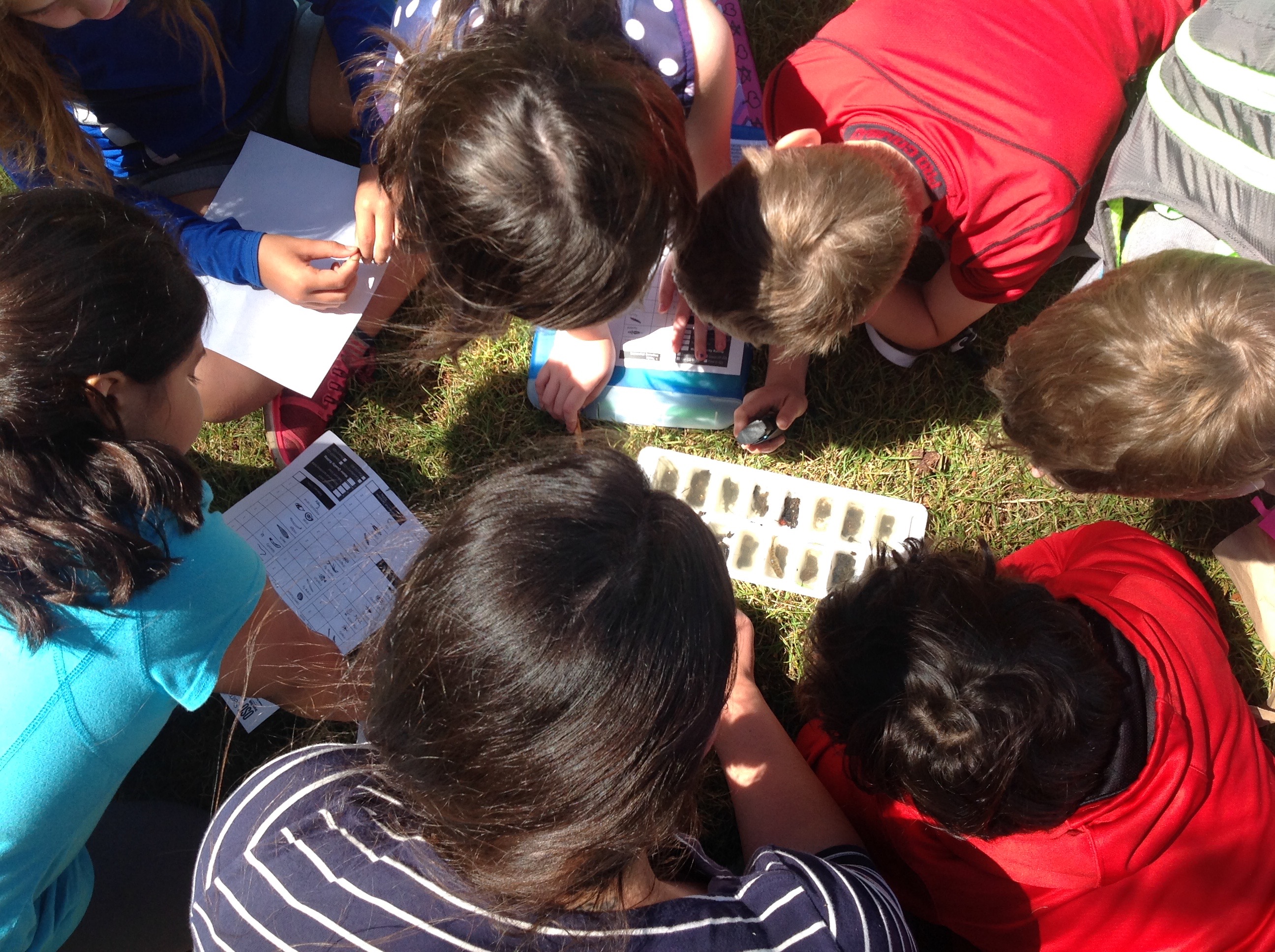

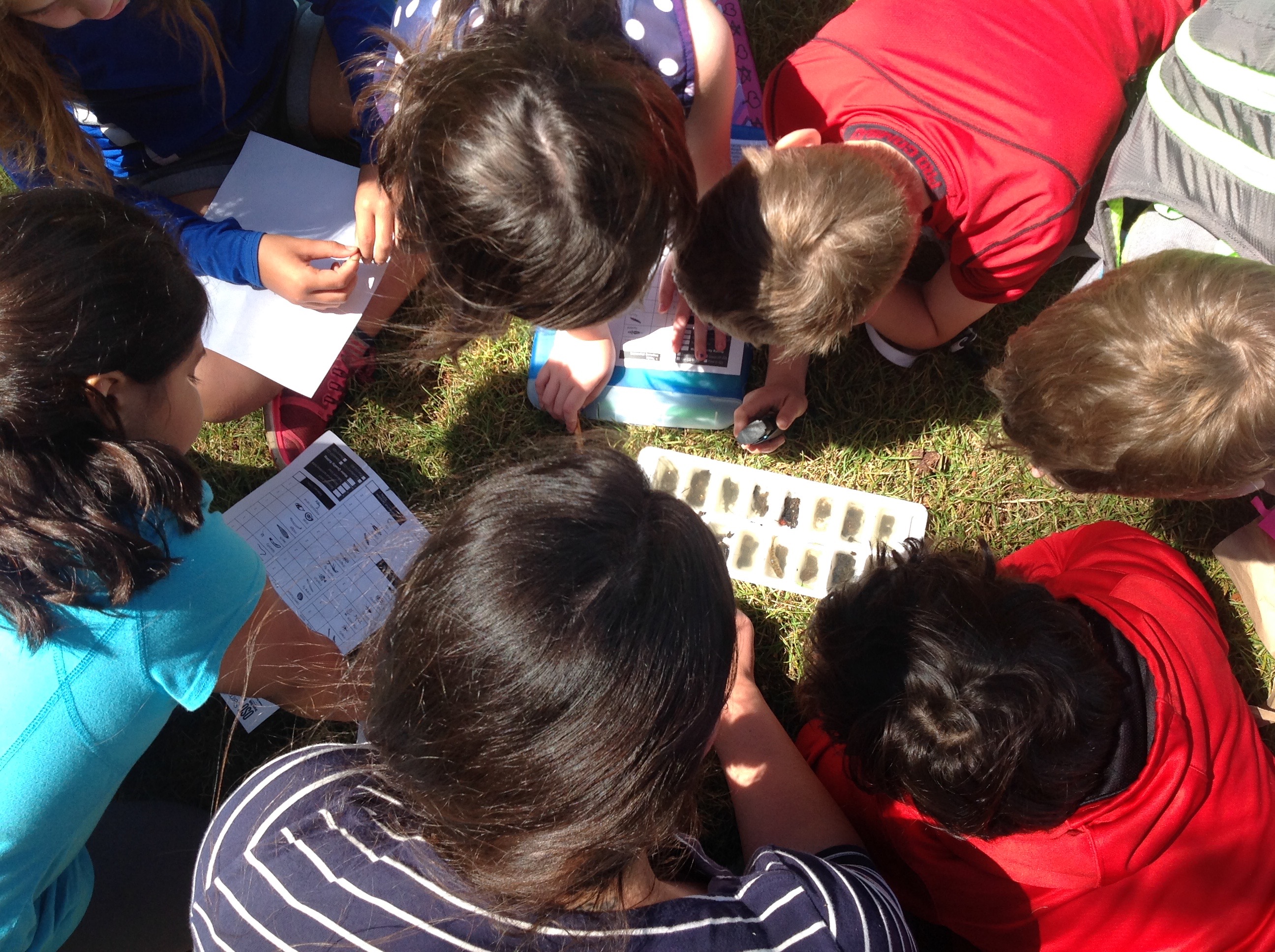

I have spent most of my time in the outdoor education world working with the BEETLES Project, based at the Lawrence Hall of Science at UC Berkeley. Since its beginning in 2011, BEETLES has focused specifically on shifting the culture of outdoor teaching toward learner-centered pedagogy, encouraging instructors to be curious about students’ ideas, to represent science as a way of thinking rather than a list of facts, to help learners develop transferable thinking tools, and to focus on common and accessible parts of nature. BEETLES professional learning sessions, like “Making Observations,” offer learner- and nature-centered practices, paired with research and theory behind why they are effective. BEETLES student activities, like “Discovery Swap,” offer practical, learner-centered resources for instructors to use. Supporting resources, such as “Engaging and Managing Students in Outdoor Science” and “BEETLES Guide for Outdoor Science Program and Organization Leaders,” offer general support for instructors and organizations.

Prior to working for the BEETLES Project, I was an instructor at residential outdoor education schools, where I spent every day outside with students. My goal was to offer learners a range of different ways for being outdoors, from direct observation and close study of organisms to discussions of environmental issues to nature journaling to exuberant play. I also called on my love of poetry and facilitated writing exercises with students. I found that learner-centered, observation-based teaching practices and nature journaling in particular fed easily into poetry. My poetry eye quickly noticed that lists of observations, questions, and connections that students said out loud often sounded a lot like poetry––which is teeming with observations, questions, and connections. It wasn’t hard to encourage budding young writers to transform their scrawled notes, memories, and firsthand observations into poems, which they were often eager to share.

Ada Limón, the national poet laureate, says, “Poetry offers us a way to be closer to who you are.” In my experience, poetry also offers us a way to be closer to where we are through the process of careful observation, as in Brooke Maren Yokell’s poem:

My Backyard in the Spring

Brooke Maren Yokell, third grade

I sit in the backyard for

hours looking up and noticing the

clouds swiftly drift by

When I’m there I hear the bees

buzzing, the birds chirping

and wind gently blowing the trees.

I let the low wind hit my face

with warm spring air.

I let the warm air flood through

my body.

I sink into the

hot grass trying

to figure out

the shapes of

the clouds. The

wind gently pushes the

trees toward us.

Writing and sharing poetry in the context of environmental learning supports learner-centered teaching, making room for students to share their perspectives and experiences, as in Lena Nguyen’s poem:

My Old Old Old neighborhood

Lena Nguyen, third grade

My old old old neighborhood

where I used to live

was a home to me.

It had everything I needed.

Playground behind my house.

And every time I was sad

it would calm me with

sweet hushing rain.

When I was not scared

it would scare me with thunder.

If I was bored it would let

the sun out and welcome me to play.

Every year it would celebrate

with different decorated trucks

depending on the year.

My old old old neighborhood

used to cheer me up all the time.

Writing poetry is also a way to reflect on responsibility, making sound choices, and reflecting how actions may impact communities, places, and people––as in Ada Limón’s “A New National Anthem.” Writing poetry offers a way to slow down, notice, and adorn the ordinary with attention, as the luminous poet Naomi Shihab Nye describes in “Valentine for Ernest Mann.” And, writing poetry can be a way to name and cherish meaningful memories of places, people, and communities, as in my own poem about elders teaching children how to plant seeds.