by editor | Sep 20, 2025 | Data Collection, Environmental Literacy, Experiential Learning, Forest Education, Inquiry, Integrating EE in the Curriculum, Learning Theory, Marine/Aquatic Education, Questioning strategies

Building a Community: The Value of a Diack Teacher Workshop

Teachers are being asked to do more than ever before. We are inundated with meetings, grading, analyzing data and curriculum development. The idea of taking kids outside to do field-based research can be daunting and filled with bureaucratic hurdles. Given all this, why should we take our precious time to implement this new type of learning?

by Tina Allahverdian

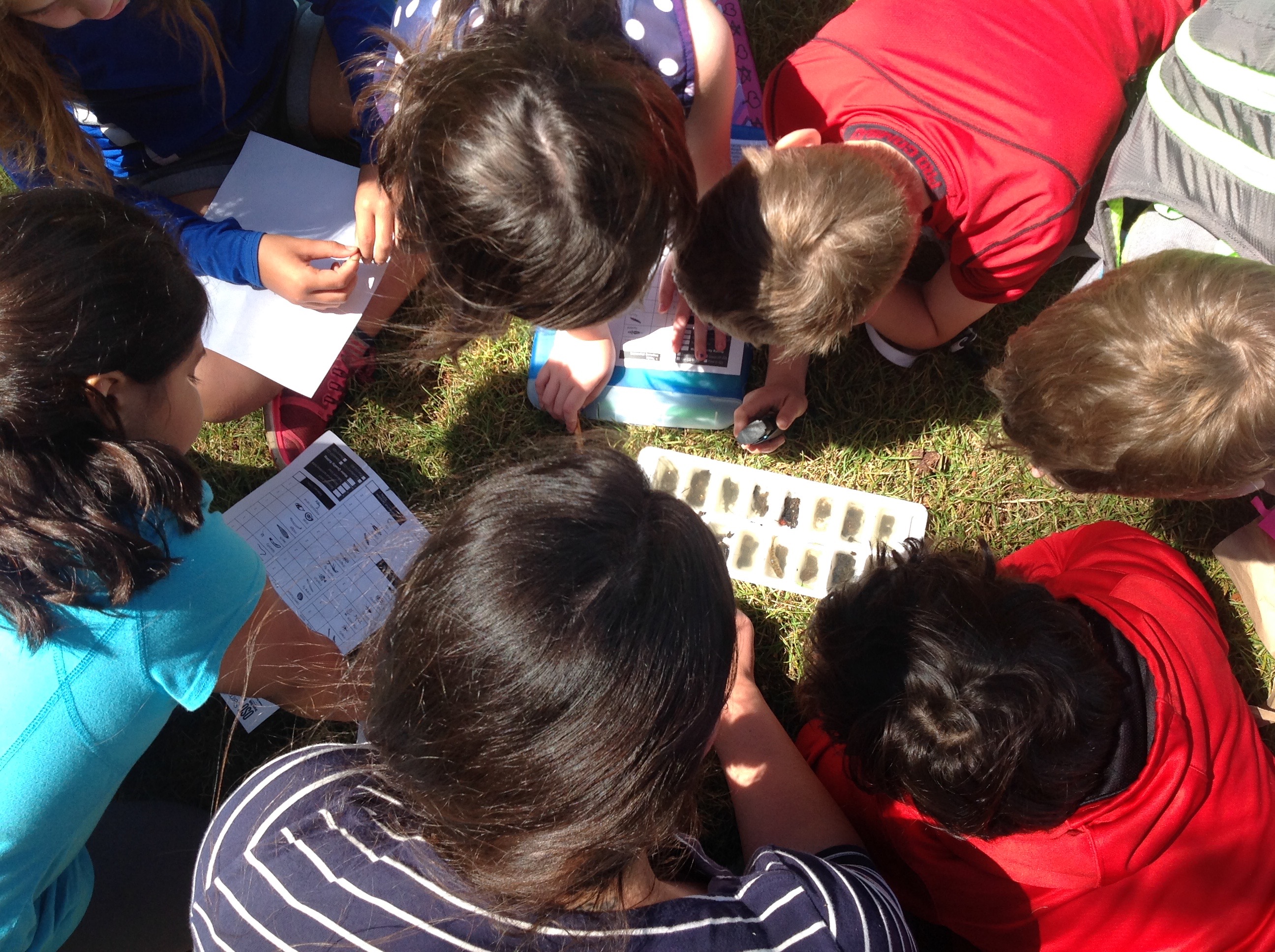

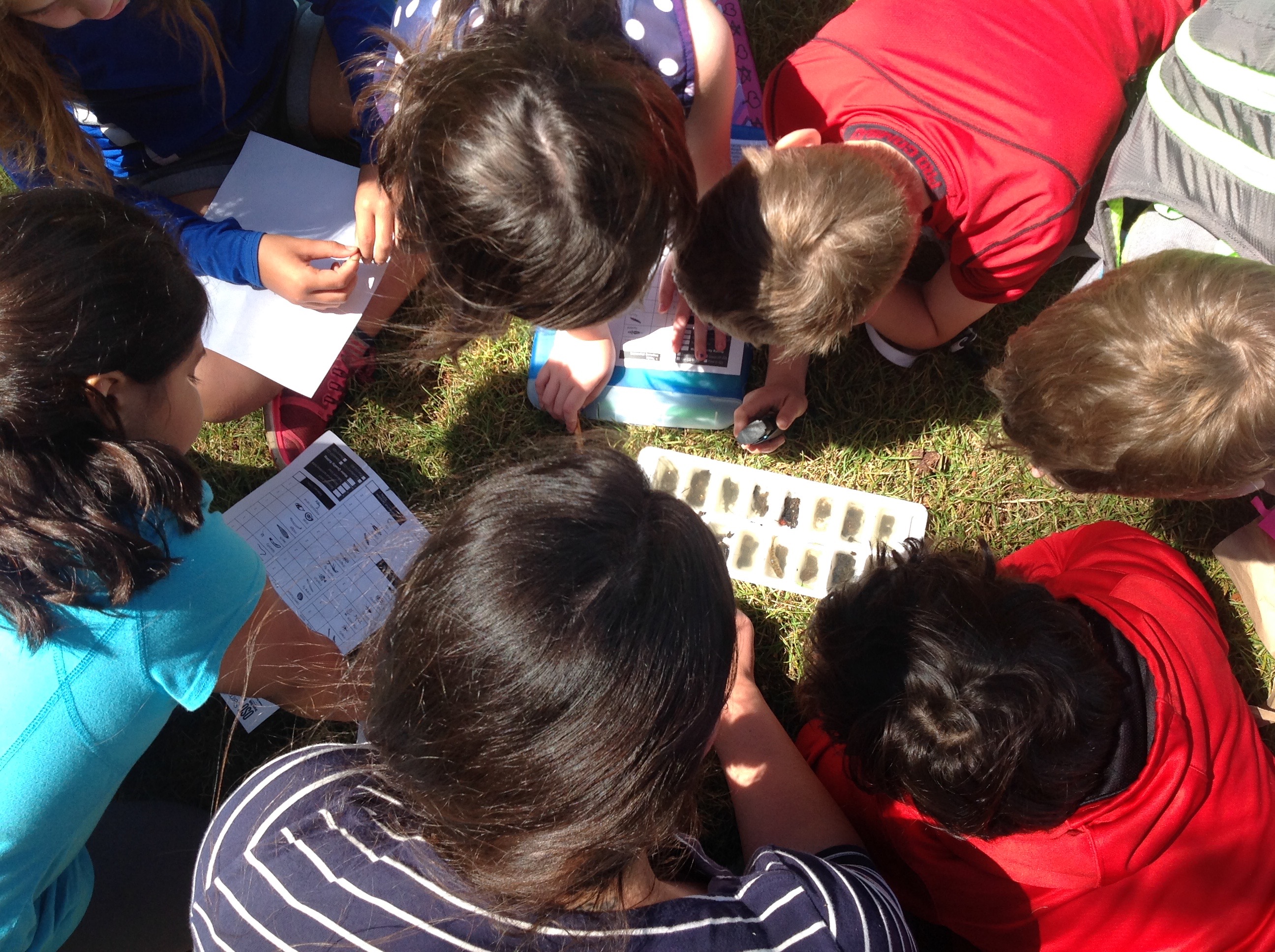

It is a warm summer day at Silver Falls State Park and a group of teachers are conducting a macroinvertebrate study on the abundance and richness of species around the swimming hole. The air is filled with sounds of laughter from children playing, parents conversing on the bank, and the gentle babble of the stream below the dam. The teachers, armed with Dnets, clipboards, and other sampling equipment, move purposefully through the water collecting aquatic species. Being a leader at this unique workshop, I am there to support the teacher’s inquiry project and also help brainstorm ways to bring this type of work back to their classrooms.

It is a warm summer day at Silver Falls State Park and a group of teachers are conducting a macroinvertebrate study on the abundance and richness of species around the swimming hole. The air is filled with sounds of laughter from children playing, parents conversing on the bank, and the gentle babble of the stream below the dam. The teachers, armed with Dnets, clipboards, and other sampling equipment, move purposefully through the water collecting aquatic species. Being a leader at this unique workshop, I am there to support the teacher’s inquiry project and also help brainstorm ways to bring this type of work back to their classrooms.

The buckets on the bank soon host a variety of species like water beetles, caddisflies, and stonefly nymphs, offering a snapshot of the rich biodiversity in the stream. We teachers sit on the bank, peering into the tubs, magnifying lenses and field guides in hand. We fill out data collection forms and discuss our findings. On this particular summer day, several young children at the park gather to see what we are doing. Their curiosity is piqued by the idea of discovering the hidden inhabitants of the aquatic ecosystem they are swimming in. The teachers and I patiently explain the project to the children and their parents. While some of the crowd goes back to swimming, two little girls stay for over an hour to help identify species. Later, while we pack up a mother stops to thank us for including her daughter in the scientific process. She shares that discovering the magic of the stream with us is her daughter’s idea of a perfect day. This moment is a testament to the power of experiential learning and the unexpected magic that can happen when we take learning into the field.

After the field work is completed, we all gather back at the lodge to create posters and present our results to the rest of the workshop participants. Based on individual interests and grade levels, teachers work in small groups to analyze their data and share their conclusions and questions. There are various topics that groups are curious about — from lichen or moss, to bird behavior and effects of a recent fire on the tree species. Teachers take on the work of scientists so they can get a feel for the experience their students will have in the future.

Teachers often want to backwards plan, knowing the end product their students will experience and learn. But this type of scientific inquiry requires us to let go of control so that students can ask authentic, meaningful questions that are not yet answered. Teachers come to learn that teaching the process of science is often more valuable than teaching the content. They are engaging in the work of true scientists and learning how to be curious, lifelong learners along the way. Being a part of inspiring projects and trips such as these is an experience that teachers, students, and even parent volunteers will remember for years to come. As an upper elementary teacher myself, I often hear about the power of our work when families come back to visit and reminisce about their time in my classroom. I know that this work will impact future generations and their enthusiasm for science learning. Not only that, we are teaching students to do, read and understand the work of a scientist so they can make informed choices in their adult lives.

Teachers often want to backwards plan, knowing the end product their students will experience and learn. But this type of scientific inquiry requires us to let go of control so that students can ask authentic, meaningful questions that are not yet answered. Teachers come to learn that teaching the process of science is often more valuable than teaching the content. They are engaging in the work of true scientists and learning how to be curious, lifelong learners along the way. Being a part of inspiring projects and trips such as these is an experience that teachers, students, and even parent volunteers will remember for years to come. As an upper elementary teacher myself, I often hear about the power of our work when families come back to visit and reminisce about their time in my classroom. I know that this work will impact future generations and their enthusiasm for science learning. Not only that, we are teaching students to do, read and understand the work of a scientist so they can make informed choices in their adult lives.

Every time I help lead this workshop, I witness a transformation among the participants over the course of the three days. On the last day we give a feedback form which is always filled with so much enthusiasm for taking the learning back to the classroom and to colleagues; I often hear this is the best professional development they have experienced in a long time because it is so practical and hands-on. One of my favorite parts about the Diack field science workshops is witnessing the teacher’s excitement for learning about nature that I know will be passed on to students back in the classroom. Twice a year we meet at a beautiful location in Oregon where teachers from many different districts have the opportunity to carry out the mini-inquiry project and plan curriculum that promotes student-driven, field based science inquiry for K-12 students.

Perhaps one of the most significant outcomes of the Diack Ecology Workshop is the formation of a community of educators passionate about outdoor learning. Teachers exchange ideas, share success stories, and collaborate on developing resources for implementing field-based inquiry projects. They share ideas across grade levels to get a sense of where their students are going and have come from. This sense of community not only strengthens the impact of the program but also creates a support network for educators venturing into the world of environmental education. I always leave the workshop inspired by the creativity, collaboration, and joy from teachers. It is one of my favorite parts of the summer and I would encourage anyone who works with students to come join us and experience the magic.

Tina Allahverdian is passionate about connecting students with science in the natural world. When not teaching fifth graders, she can be found reading in a hammock, kayaking through Pacific Northwest waters, or hiking in the mountains. She currently teaches in West Linn, Oregon, and resides in SE Portland with her husband, twin boys, and their dog, Nalu.

Tina Allahverdian is passionate about connecting students with science in the natural world. When not teaching fifth graders, she can be found reading in a hammock, kayaking through Pacific Northwest waters, or hiking in the mountains. She currently teaches in West Linn, Oregon, and resides in SE Portland with her husband, twin boys, and their dog, Nalu.

by editor | Sep 12, 2025 | Environmental Literacy, Inquiry, Language Arts, Learning Theory, Teaching Science

The wild turkeys on my street don’t wear booties in the winter and the mouse in my house doesn’t wear bonnets from a closet! Should environmental education start with realism in the early years?

by Suzanne Major Ph.D.

Anthropology of Early Childhood Education

Books and movies have made animals, insects and plants so charming and sympathetic, and at times so frightfully magnificent and impressive. Can young children do without these entertaining animations and anthropomorphism, that is, making animals, insects and plants look and behave like humans? Do we dress them up, make them talk and have them drink tea from porcelain cups because we don’t know anything about them? Or do we think that young children can’t appreciate them for what they are? Young children across the world easily demonstrate that they are capable of perceiving, observing and remembering the descriptive elements belonging to an animal, a plant or insect. They can collect information and draw knowledge from it. My friend Omar in Cairo, three years old, knows not to treat the wild dogs as pets if only, because they are infested with fleas. My neighbour Maddy learned at two-years-old not to bother the bees in the hive hanging from the apple tree. Jenny, in Moncton New Brunswick, four years old, can identify the leaves of poison ivy in the forest and knows to wear long pants to protect her legs when she goes for walks with her family. Children learn very early on what is dangerous or not, comestible or not, pleasant or disagreeable. They are also capable of attaching symbolic value to things. Children everywhere offer flowers to their mothers and grandmothers to express their feelings or to create a nice event! As you know, they learn using observation, imitation, repetition or as Piaget wrote “perception, assimilation and accommodation”. They also identify with the knowledge of others or the information offered by nature. They encode it just because others use it, or they happened to observe it. They sometimes need information quickly, so they identify with the information others have, to fill the gap until they can adapt or replace it with more personal information. Through a very individualistic process of thought creation they retain or ignore elements of information and knowledge. They set the ones they favour in memory and replay others in thought, all sorts of ways assessing what works or not.

Finding animals, insects, plants or things cute, vulnerable or charming stems from the capability of empathy which is more difficult to use for what is ugly, threatening or disgusting. This notion of finding things cute is a cultural one that is cultivated and exploited by stories, books, animations and movies. Empathy is used to ensure survival among our own and can be transferred to animals, insects and plants. But it also allows sentiments to emerge that can be directed, intentions that can be instructed and behaviours that can be modelled. It is often used because of marketing interests but it can also serve pedagogically to create empathy. “Charlotte, the spider” is a good example!

The question here is do we need to create stories to nurture environmental education with children? Are we trying to sell them nature? Do we need to manipulate them towards environmental education or can we let them acquire a more significant first-hand experience? Should we not have a more functional approach about how everything has a place and time and is part of a balance of all and everything in the universe? Should we not let nature imprint itself on children, so they can sense by themselves their place on earth? Is that not fascinating enough? Let’s take the booties and the bonnets off the turkeys and the mice on these pages to see where this can go! Pink and white mice are mammals of the order of Rodentia and the genus MUS.[1] Wikipedia tells us that they are climbers, jumpers and swimmers and have lots of energy. They use their tail for tripoding so they can observe, listen and feel their environment. They can sense surface and air movements with their whiskers and use pheromones for communication. It is difficult for them to survive away from human settlements and in our houses, they actually become domesticated! They eat plant matter or anything else they can get their paws on. They will even eat their own feces for nutrients produced by intestinal bacteria. They are great at reproducing. They have a 19 to 21 days gestation, have 3 to 14 pups and 5 to 10 litters a year and females are sexually mature at 6 weeks. Do the math! We like them outside in the fields and not in our houses. Where I live, coyotes can hear and smell them and eagerly feast on them. Small falcons and owls can see them easily and pick them up in a flash. Last summer was very warm and wet. The vegetation exploded as well as the mice population. As I walked in my garden, they would jump up right and left to move away from me.

What can we infer from this information for environmental education? Young children spontaneously sit on their legs, hold up their bent hands and wiggle their noses to imitate mice. By observing mice and comparing their bodies with them, young children can engage in an array of locomotive and motor activities. Experimenting with sensing surfaces and air movements with their skin and their hair they can discover how this gives them information and knowledge. They can explore and sense space with the whole body like the security of a small shelter and the unsettling feeling of wide-open spaces. Discovering smells and odours for two and three-year- olds can be a lot of fun and for older children, linking those to chemical reactions can awake them to science. Seeking the mice out in the fields can be very interesting as they make little tunnels that go everywhere under the snow and through the dried grass. Reflecting with young children over three years old on the mice population in relation to the weather and the consequences this brings is interesting because the phenomenon attracts coyotes near houses which creates a real threat to house pets and small farm animals.

Let’s consider wild turkeys or Meleagris Gallopavo. Wikipedia informs us that the females are called hens and the males are known as toms. The males have huge tails they fan out to attract the females and impress the other males. They have up to 6,000 feathers and they can fly for 400 metres. To protect themselves from storms, they can roost up to 16 metres above ground in tall conifers. They gobble and emit a low-pitched drumming sound. If cornered, they can be aggressive towards humans. They are omnivores but prefer nuts, seeds and berries. They will eat amphibians, snakes and reptiles. Their babies are called poults. The hens lay 10 to 14 eggs and incubate for 28 days and the little ones are ready to go 12 to 24 hours after hatching. They can fall prey to coyotes, grey wolfs, lynxes and foxes.

The adults are around four feet tall and the big males can weigh some 37 pounds. I observe them regularly around my house. Hens flock together with the young ones, 12 or 14 together as they walk around the fields and woods. When they cross the road, one leads on and at least one or two stay behind to gather everyone. They are very attentive, looking right and left and right again. One might even stand guard in the middle of the street to make sure everyone has crossed. I am told they made a comeback in recent years as they had disappeared because of over hunting. At night in the summer, when there is a storm, we can hear them gobble after each clap of thunder.

What can we infer from this information for environmental education? It’s a magnificent bird when it struts around displaying its beautiful black tail, but I reckon a young child would be impressed even afraid if it came face to face with a tom or a hen on the street or in the back yard. It certainly offers the opportunity to acquire new vocabulary with the wattle or snood hanging from its beak, the caruncles pending from its neck, its hairless head crown and beard or beards on a single bird, the spurs on the back of its legs and the three long toes on its feet. Two and three- year-olds would delight in knowing by heart the body parts of the wild turkey and comparing it with the ones of a chicken. Young children would also be impressed to measure themselves against the life-size drawing of a male turkey. Three and four-year-olds could explore what low-pitch drumming sounds are and could discuss why the turkeys gobble after the clap of thunder and even do a little research. As an educator, I would not miss the chance to make a parallel between the turkeys looking right and left and right again before crossing the street and children attempting to do the same but unable to fly away from danger! Finally, with older children it would be interesting to place the mice, the turkeys and the coyotes in their environment and talk about the relation between them.

Nature provides real and fascinating animations all by herself and children can appreciate the reality of animals, insects and plants. All sorts of elements can create the desire for observation and exploration. Exploration calls on focus which brings attention to details which creates in turn the need for manipulation. Manipulation and/or representation will lead to curiosity for functions which is knowledge. Knowledge for young children establishes the feeling of competence. Competence cultivates initiatives and permits the experience of trials and successes. In turn, the need and the pleasure for demonstration can take place, then patience to practice, to persist and develop skills becomes a reality. Later, mastering will open the cognitive door to metaknowledge.

Observation, exploration, focus, manipulation, representation, curiosity, knowledge, competence, initiative, demonstration, patience, mastering, metaknowledge, is a pedagogical sequence that young children can start experiencing when they are just a few months old.

Suzanne Major is an anthropologist and early childhood educator. She received her Ph. D. in 2015, with mention of excellence, in Anthropology of Early Childhood Education from the University of Montreal, Quebec, Canada. She also has a master’s degree in Child Studies which was obtained in 2004 at Concordia University, in Montreal, Canada. She has worked 12 years as Director for the Early Childhood Studies Program of the University of Montreal’s Faculty of Permanent Education.

Suzanne Major is an anthropologist and early childhood educator. She received her Ph. D. in 2015, with mention of excellence, in Anthropology of Early Childhood Education from the University of Montreal, Quebec, Canada. She also has a master’s degree in Child Studies which was obtained in 2004 at Concordia University, in Montreal, Canada. She has worked 12 years as Director for the Early Childhood Studies Program of the University of Montreal’s Faculty of Permanent Education.

by editor | Sep 7, 2025 | Critical Thinking, Environmental Literacy, Experiential Learning, Integrating EE in the Curriculum, K-12 Activities, Language Arts, Learning Theory

by Jim McDonald

The demands on classroom teachers to address a variety of different subjects during the day means that some things just get left out of the curriculum. Many schools have adopted an instructional approach with supports for students that teach reading and math, with the addition of interventions to teach literacy and numeracy skills which take up more time in the instructional schedule. In some of the schools that I work with there is an additional 30 minutes a day for reading intervention plus 30 more minutes for math intervention. So, we are left with the question, how do I fit time for science or environmental education into my busy teaching schedule?

In a recent STEM Teaching tools brief on integration of science at the elementary level, it was put this way:

We do not live in disciplinary silos so why do we ask children to learn in that manner? All science learning is a cultural accomplishment and can provide the relevance or phenomena that connects to student interests and identities. This often intersects with multiple content areas. Young children are naturally curious and come to school ready to learn science. Leading with science leverages students’ natural curiosity and builds strong knowledge-bases in other content areas. Science has taken a backseat to ELA and mathematics for more than twenty years. Integration among the content areas assures that science is given priority in the elementary educational experience (STEM Teaching Tool No. 62).

Why does this matter? Educators at all levels should be aware of educational standards across subjects and be able to make meaningful connections across the content disciplines in their teaching. Building administrators look for elementary teachers to address content standards in math, science, social studies, literacy/English Language arts at a minimum plus possibly physical education, art, and music. What follows are some things that elementary teachers should consider when attempting integration of science and environmental education with other subjects.

Things to Consider for Integration

The integration of science and environmental education concepts with other subjects must be meaningful to students and connect in obvious ways to other content areas. The world is interdisciplinary while the experience for students and teachers is often disciplinary. Learning takes place both inside and outside of school. Investigations that take place outside of school are driven by people’s curiosity and play and often cut across disciplinary subjects. However, learning in school is often fragmented into different subject matter silos.

Math and reading instruction dominate the daily teaching schedule for a teacher because that is what is evaluated on standardized tests. However, subjects other than ELA and math should be kept in mind when considering integration. Social studies and the arts provide some excellent opportunities for the integration of science with other content areas. In the NGSS, the use of crosscutting concepts support students in making sense of phenomena across science disciplines and can be used to prompt student thinking. They can serve as a vehicle for teachers to see connections to the rest of their curriculum, particularly English/Language Arts and math. Crosscutting concepts are essential tools for teaching and learning science because students can understand the natural world by using crosscutting concepts to make sense of phenomena across the science disciplines. As students move from one core idea to another core idea within a class or across grade-levels, they can continually utilize the crosscutting concepts as consistent cognitive constructs for engaging in sense-making when presented with novel, natural phenomena. Natural phenomena are observable events that occur in the universe and we can use our science knowledge to explain or predict phenomena (i.e., water condensing on a glass, strong winds preceding a rainstorm, a copper penny turning green, snakes shedding their skin) (Achieve, 2016).

Reading

Generally, when I hear about science and literacy, it involves helping students comprehend their science textbook or other science reading. It is a series of strategies from the field of literacy that educators can apply in a science context. For example, teachers could ask students to do a “close reading” of a text, pulling out specific vocabulary, key ideas, and answers to text-based questions. Or, a teacher might pre-teach vocabulary, and have students write the words in sentences and draw pictures illustrating those words. Perhaps students provide one another feedback on the effectiveness of a presentation. Did you speak clearly and emphasize a few main points? Did you have good eye contact? Generally, these strategies are useful, but they’re not science specific. They could be applied to any disciplinary context. These types of strategies are often mislabeled as “disciplinary literacy.” I would advocate they are not. Disciplinary literacy is not just a new name for reading in a content area.

Scientists have a unique way of working with text and communicating ideas. They read an article or watch a video with a particular lens and a particular way of thinking about the material. Engaging with disciplinary literacy in science means approaching or creating a text with that lens. Notably, the text is not just a book. The Wisconsin DPI defines text as any communication, spoken, written, or visual, involving language. Reading like a scientist is different from having strategies to comprehend a complex text, and the texts involved have unique characteristics. Further, if students themselves are writing like scientists, their own texts can become the scientific texts that they collaboratively interact with and revise over time. In sum, disciplinary literacy in science is the confluence of science content knowledge, experience, and skills, merged with the ability to read, write, listen, and speak, in order to effectively communicate about scientific phenomena.

As a disciplinary literacy task in a classroom, students might be asked to write an effective lab report or decipher the appropriateness of a methodology explained in a scientific article. They might listen to audio clips, describing with evidence how one bird’s “song” differs throughout a day. Or, they could present a brief description of an investigation they are conducting in order to receive feedback from peers.

Social Studies

You can find time to teach science and environmental education and integrate it with social studies by following a few key ideas. You can teach science and social studies instead of doing writer’s workshop, choose science and social studies books for guided reading groups, and make science and social studies texts available in your classroom library.

Teach Science/Social Studies in Lieu of Writer’s Workshop: You will only need to do this one, maybe two days each week. Like most teachers, I experienced the problem of not having time to “do it all” during my first year in the classroom. My literacy coach at the time said that writer’s workshop only needs to be done three times each week, and you can conduct science or social studies lessons during that block one or two times a week. This was eye-opening, and I have followed this guidance ever since. My current principal also encouraged teachers to do science and social studies “labs” once a week during writing time! Being able to teach science or social studies during writing essentially opens up one or two additional hours each week to teach content! It is also a perfect time to do those activities that definitely take longer than 30 minutes: science experiments, research, engagement in group projects, and so forth. Although it is not the “official” writers workshop writing process, there is still significant writing involved. Science writing includes recording observations and data, writing steps to a procedure/experiment, and writing conclusions and any new information learned. “Social studies writing” includes taking research notes, writing reports, or writing new information learned in a social studies notebook. Students will absolutely still be writing every day.

Choose Science and Social Studies Texts for Guided Reading Groups: This suggestion is a great opportunity to creatively incorporate science and social studies in your weekly schedule. When planning and implementing guided reading groups, strategically pick science and social studies texts that align to your current unit of study throughout the school year. During this time, students in your guided reading groups can have yet another opportunity to absorb content while practicing reading strategies.

Make Science and Social Studies Texts Available and Accessible in Your Classroom Library: During each unit, select texts and have “thematic unit” book bins accessible to your students in a way that is best suited for your classroom setup. Display them in a special place your students know to visit when looking for books to read. When kids “book-shop” and choose their just-right books for independent reading, encourage them to pick one or two books from the “thematic unit” bin. They can read these books during independent reading time and be exposed to science and social studies content.

Elementary Integration Ideas

Kindergarten: In a kindergarten classroom, a teacher puts a stuffed animal on a rolling chair in front of the room. The teacher asks, “How could we make ‘Stuffy’ move? Share an idea with a partner”. She then circulates to hear student talk. She randomly asks a few students to describe and demonstrate their method. As students share their method, she will be pointing out terms they use, particularly highlighting or prompting the terms “push” and “pull”. Next, she has students write in their science notebooks, “A force is a push or a pull”. This writing may be scaffolded by having some students just trace these words on a worksheet glued into the notebook. Above that writing, she asks students to draw a picture of their idea, or another pair’s idea, for how to move the animal. Some student pairs that have not shared yet are then given the opportunity to share and explain their drawing. Students are specifically asked to explain, “What is causing the force in your picture?”.

For homework, students are asked to somehow show their parents a push and a pull and tell them that a push or a pull is a force. For accountability, parents could help students write or draw about what they did, or students would just know they would have to share the next day.

In class the next day, the teacher asks students to share some of the pushes and pulls they showed their parents, asking them to use the word force. She then asks students to talk with their partner about, “Why did the animal in the chair sometimes move far and sometimes not move as far when we added a force?”. She then asks some students to demonstrate and describe an idea for making the animal/chair farther or less far; ideally, students will push or pull with varying degrees of force. Students are then asked to write in their notebooks, “A big force makes it move more!” With a teacher example, as needed, they also draw an image of what this might look like.

As a possible extension: how would a scientist decide for sure which went further? How would she measure it? The class could discuss and perform different means for measurement, standard and nonstandard.

Fourth Grade Unit on Natural Resources: This was a unit completed by one group of preservice teachers for one of my classes. The four future elementary teachers worked closely in their interdisciplinary courses to design an integrated unit for a fourth-grade classroom of students. The teachers were given one social studies and one science standard to build the unit around. The team of teachers then collaborated and designed four lessons that would eventually be taught in a series of four sessions with the students. This unit worked to seamlessly integrate social studies, English language arts, math, and science standards for a fourth-grade classroom. Each future teacher took one lesson and chose a foundation subject to build their lesson upon. The first lesson was heavily based on social studies and set the stage for the future lessons as it covered the key vocabulary words and content such as nonrenewable and renewable resources. Following that, students were taught a lesson largely based on mathematics to better understand what the human carbon footprint is. The third lesson took the form of an interactive science experiment so students could see the impact of pollution on a lake, while the fourth lesson concluded with an emphasis on language arts to engage students in the creation of inventions to prevent pollution in the future and conserve the earth’s resources. Contrary to the future educators’ initial thoughts, integrating the various subject areas into one lesson came much more easily than expected! Overall, they felt that their lessons were more engaging than a single subject lesson and observed their students making connections on their own from previously taught lessons and different content areas.

References

Achieve. (2016). Using phenomena in NGSS-designed lessons and units. Retrieved from https://www.nextgenscience.org/sites/default/files/Using%20Phenomena%20in%20NGSS.pdf

Hill, L., Baker, A., Schrauben, M. & Petersen, A. (October 2019). What does subject matter integration look like in instruction? Including science is key! Institute for Science + Math Education. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Retrieved from: http://stemteachingtools.org/brief/62

Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction. (n.d.) Clarifying literacy in science. Retrieved from: https://dpi.wi.gov/science/disciplinary-literacy/types-of-literacy

Jim McDonald is a Professor of Science Education at Central Michigan University in Mt. Pleasant, Michigan. He teaches both preservice teachers and graduate students at CMU. He is a certified facilitator for Project WILD, Project WET, and Project Learning Tree. He is the Past President of the Council for Elementary Science International, the elementary affiliate of the National Science Teaching Association.

Jim McDonald is a Professor of Science Education at Central Michigan University in Mt. Pleasant, Michigan. He teaches both preservice teachers and graduate students at CMU. He is a certified facilitator for Project WILD, Project WET, and Project Learning Tree. He is the Past President of the Council for Elementary Science International, the elementary affiliate of the National Science Teaching Association.

by editor | Sep 7, 2025 | Conservation & Sustainability, Critical Thinking, Environmental Literacy, Experiential Learning, Learning Theory, Questioning strategies, Service learning, Sustainability

Empowering Elementary Students through Environmental Service-Learning

by Eileen Merritt, Tracy Harkins and Sara Rimm-Kaufman

“We use electricity when we don’t need to.”

“When we use electricity we use fossil fuels and fossil fuels pollute the air and fossil fuels are nonrenewable.”

“We use too many non-renewable resources to make energy.”

“One problem that we have with the way that we use energy is that we often taken it for granted, leaving lights on when it’s unnecessary, and plugging in chargers without using them.”

“We are literally putting pollution on the blanket of the earth!?”

The problems listed above were identified by fourth grade students in the midst of an environmental service-learning unit. These powerful words, and many similar ideas shared with us by other fourth grade children, show that children care a lot about our planet. They notice when we waste resources, pollute our air, water or land, or cause harm to other living things. Their concerns must be heard, to motivate others to confront the environmental crises that we are facing today. Greta Thunberg has recently demonstrated how powerful one young voice can be, mobilizing people around the world to take action on climate change.

How can educators help students develop skills to be change agents, offering creative and feasible solutions to problems they see around them? Service-learning is one powerful way to build students’ knowledge and skills as they learn about issues that matter to them. Recently, we worked with a group of urban public school teachers to support implementation of environmental service-learning projects in their classrooms. In environmental service-learning, students apply academic knowledge and skills as they work together to address environmental problems. High quality service-learning, according to the National Youth Leadership Council (NYLC), provides opportunities for students to have a strong voice in planning, implementing and evaluating projects with guidance from adults and engages students in meaningful and personally relevant service activities that address content standards (NYLC, 2008). We designed Connect Science, a curriculum and professional development program, with these goals in mind (Harkins, Merritt, Rimm-Kaufman, Hunt & Bowers, 2019). As we have analyzed student data from this research study, we have been inspired by the strength of conviction that students conveyed when they spoke about the environment and the creative solutions they generated for problems they noticed. In this article, we describe key elements of lessons that fostered student agency (see Table 1). First, two vignettes below exemplify service-learning projects from two classrooms.

In another classroom, students launched a campaign to reduce the use of disposable plastic containers at their school. They made posters to educate others about single-use plastics, explaining how they were made from petroleum (see Figure 1). Students and teachers in their school were encouraged to take a pledge to use reusable water bottles, containers and utensils in their lunches. Sign-up sheets were placed near posters around the school. Several hundred people took the pledge.

In another classroom, students launched a campaign to reduce the use of disposable plastic containers at their school. They made posters to educate others about single-use plastics, explaining how they were made from petroleum (see Figure 1). Students and teachers in their school were encouraged to take a pledge to use reusable water bottles, containers and utensils in their lunches. Sign-up sheets were placed near posters around the school. Several hundred people took the pledge.

What both groups have in common is that they participated in a science unit about energy and natural resources. In the first part of the unit, they discovered problems as they learned about different energy sources and how these energy sources produce electricity. They began to recognize that fossil fuels that are used for transportation, electricity production and plastic products, and that their use causes some problems. This awareness motivated them to take action. Later in the unit, each class honed in on a specific problem that they cared about and chose a solution. Below, we summarize steps taken throughout the unit that empowered students.

1 Choose an environmental topic and help students build knowledge

Students need time to develop a deep understanding of the content and issues before they choose a problem and solution. Many topics are a good fit for environmental service-learning. Just identify an environmental topic in your curriculum. Our unit centered around NGSS core idea ESS3A: How do humans depend on earth’s resources? (National Research Council, 2012). Students participated in a series of lessons designed to help them understand energy concepts and discover resource-related problems. These lessons can be found on our project website: connectscience.org/lessons. Fourth grade students are capable of understanding how the energy and products they use impact the planet (Merritt, Bowers & Rimm-Kaufman, 2019), so why not harness their energy for the greater good?

There are many other science concepts from NGSS that can be addressed through environmental service-learning. For example, LS4.D is about biodiversity and humans, and focuses on the central questions: What is biodiversity, how do humans affect it, and how does it affect humans? Environmental service-learning can be used to address College, Career and Civic Life (C3) standards from dimension 4, taking informed action such as D4.7 (grades 3-5): Explain different strategies and approaches students and others could take in working alone and together to address local, regional, and global problems, and predict some possible results of their actions (National Council for the Social Studies, 2013). Language arts and mathematics standards can also be taught and applied within a service-learning unit.

2 Generate a list of related problems that matter to students

Partway through the unit, each class started a list of problems to consider for further investigation. Collecting or listing problems that kids care about is an effective way to get a pulse on what matters to students. Fourth graders’ concerns fit into three broad categories:

• Pollution (air, water or land)

People need to stop littering. Before you even throw everything on the floor, think about it in your head… should I recycle, reuse? I can probably reuse this…

• Not causing harm to people, animals or the environment

Plastic bags suffocate animals.

• Wasting resources (e.g. electricity, natural resources or money)

If people waste energy, then their bill will get high and it will just be a waste of money.

Co-creating a visible list for students to see and think about legitimizes their concerns and may help them develop a sense of urgency to take action.

3 Collectively identify an important problem

The next step was for students to choose ONE problem for the upcoming service-learning project. Each teacher read the list of problems aloud, and students could cast three votes for the problems that they cared about the most. They could cast all 3 votes for one problem, or distribute their votes. Most teachers used this process to narrow in on one problem for their class to address. One teacher took it a step further by allowing small groups to work on different problems. Either way, allowing students to CHOOSE the problem they want to work on fueled their motivation for later work on solutions. Different classes honed in on problems such as wasting electricity, single-use plastics, foods being transported a long distance when they could be grown locally, and lack of recycling in their communities.

4 Explore possible solutions and teach decision-making skills

Students were introduced to three different ways that citizens can take action and create change. They can work directly on a problem, educate others in the community about the issue or work to influence decision-makers on policy to address the problem. They broadened their perspective on civic engagement as they brainstormed solution ideas in each of these categories. After deciding to work on the problem of lights left on when not in use, one class generated the following list of possibilities for further investigation (see Figure 2)

After considering ways to have an impact, students were ready to narrow in on a solution. Teachers introduced students to three criteria for a good solution. This critical step provides students with decision-making skills, and helps them take ownership of their solution. Our fourth graders considered the following guiding questions in a decision-making matrix:

After considering ways to have an impact, students were ready to narrow in on a solution. Teachers introduced students to three criteria for a good solution. This critical step provides students with decision-making skills, and helps them take ownership of their solution. Our fourth graders considered the following guiding questions in a decision-making matrix:

- Is the solution going to have a positive impact on our problem?

- Is the solution feasible?

- Do you care a lot about this? (Is it important to the group?)

At times, this process prompted further research to help them really consider feasibility. Of course, teachers needed to weigh in too, since ultimately they were responsible for supporting students as they enact solutions. When discussing impact, it’s important to help students understand that they don’t have to SOLVE the problem—the goal is to make progress or have an impact, however small.

While many groups chose the same problem, each class designed their own unique solution. Most focused on educating others about the topic that mattered to them, using a variety of methods: videos, posters, announcements, presentations to other students or administrators, and an energy fair for other members of the school community. The process of educating others about an issue can help consolidate learning (Hattie & Donoghue, 2016). Some groups took direct action in ways such as improving the school recycling program or getting others to pledge to use less electronics or less plastic (as described above). These direct actions are very concrete to upper elementary school children since impacts are often more visible.

5 Support students as they enact solutions

Social and emotional skills were addressed throughout the unit. During project implementation, teachers supported students as they applied those skills. Students developed self-management skills by listing tasks, preparing timelines and choosing roles to get the job done. At the end of the unit, students reflected on the impact that they made, and what they could do to have a larger impact. One group of students noticed that every single student in their class switched from plastic to reusable water bottles. Another student felt that their class had convinced people not to waste electricity. Some groups recognized that their solution wasn’t perfect, and wished they could have done more. For elementary students, it’s important to emphasize that any positive change makes a difference. Critical thinking skills develop when students can compare solutions and figure out which ones work the best and why. The instructional strategies described in this article have been used by educators across grade levels and subjects for other service-learning projects, and can be adapted for different purposes (KIDS Consortium, 2011).

Student-designed solutions yield deeper learning

One challenge that teachers faced when implementing environmental service-learning was that it took time to work on projects after the core disciplinary lessons, and curriculum maps often try to fast forward learning. Deeper learning occurred when teachers carved out time for service-learning projects, allowing students to apply what they know to a problem that mattered to them. There are always tradeoffs between breadth and depth, but ultimately students will remember lessons learned through experiences where they worked on a challenging problem and tried their own solution. School leaders can work with teachers to support them in finding time for deeper learning experiences. The students that we worked with cared a lot about protecting organisms and ecosystems, conserving resources and reducing pollution. They had many wonderful ideas for solutions that involved direct action, education or policy advocacy. For example, one student suggested the following solution for overuse of resources, “Go out and teach kids about animals losing homes and people polluting the world.” The voices of children around the country can be amplified through civic engagement initiatives such as environmental service-learning. Citizens of all ages are needed to actively engage in work toward solutions for climate change. Why not help them begin in elementary years?

References

Harkins, T., Merritt, E., Rimm-Kaufman, S.E., Hunt, A. & Bowers, N. (2019). Connect Science. Unpublished Manual. Charlottesville, Virginia: University of Virginia, Arizona State University & Harkins Consulting, LLC.

Hattie, J. A. & Donoghue, G. M. (2016). Learning strategies: A synthesis and conceptual model. Science of Learning, 1, 1-13.

KIDS Consortium. (2011). KIDS as planners: A guide to strengthening students, schools and communities through service-learning. Waldoboro, ME: KIDS Consortium.

Merritt, E., Bowers, N. & Rimm-Kaufman, S. (2019). Making connections: Elementary students’ ideas about electricity and energy resources. Renewable Energy, 138, 1078-1086.

National Council for the Social Studies (NCSS). (2013). The college, career, and civic life (C3) framework for social studies state standards: Guidance for enhancing the rigor of K-12 civics, economics, geography, and history. Silver Spring, Md.: NCSS. Accessible online at www.socialstudies.org/C3.

National Research Council. (2012). A framework for K-12 science education: Practices, crosscutting concepts and core ideas. Committee on a Conceptual Framework for New K-12 Science Education Standards. Board on Science Education, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

National Youth Leadership Council. (2008). K-12 service-learning standards for quality practice. St. Paul, MN: NYLC.

Acknowledgements:

The research described in this article was funded by a grant from the Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education (R305A150272). The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not represent the views of the funding agency. We are grateful to the educators, students and colleagues who shared their ideas throughout the project.

Eileen Merritt is a research scientist in the Department of Forest Resources and Environmental Conservation at Virginia Tech and former Assistant Professor in Teacher Preparation at Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College, Arizona State University. She developed her passion for environmental education along the banks of the Rivanna River with her students at Stone-Robinson Elementary. She can be reached at egmerritt@vt.edu.

Eileen Merritt is a research scientist in the Department of Forest Resources and Environmental Conservation at Virginia Tech and former Assistant Professor in Teacher Preparation at Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College, Arizona State University. She developed her passion for environmental education along the banks of the Rivanna River with her students at Stone-Robinson Elementary. She can be reached at egmerritt@vt.edu.

Tracy Harkins, of Harkins Consulting LLC, works nationally guiding educational change. Tracy provides service-learning professional development and resources to educators to engage and motivate student learners. https://www.harkinsconsultingllc.com/

Sara E. Rimm-Kaufman is a Professor of Education in Educational Psychology – Applied Developmental Science at the Curry School of Education at the University of Virginia. She conducts research on social and emotional learning in elementary and middle school classrooms to provide roadmaps for administrators and teachers making decisions for children.

by editor | Sep 7, 2025 | Critical Thinking, Environmental Literacy, Experiential Learning, Learning Theory, Sustainability

Environment, Literacy, and the Common Core

by Nancy Skerritt and Margaret Tudor, Ph.D.

ABSTRACT: This article describes how Common Core ELA standards provide an important opportunity to build background knowledge on environmental topics in preparation for a deeper study of those topics through science performance tasks guided by the Next Generation Science Standards Disciplinary Core Ideas (DCI’s).

GRADE LEVEL: K-8

The Common Core ELA standards demand a level of rigor that will challenge many students. Unlike previous curriculum reforms that were content specific, the Common Core expectations involve the integration of skills across content areas including social studies, science and language arts. Students must apply reading, writing, research, and speaking and listening to content provided through articles, speeches and videos. The new performance tasks that are a key component of Smarter Balanced assessment system require research skills, note-taking abilities, and the difficult challenge of synthesizing ideas into well-written essays or speeches that explain or advocate.

In order to engage students in these rigorous expectations, teachers must find rich content for the students to explore. Environmental issues provide relevant topics and complex problems that invite analysis and research. Students can practice and apply the ELA expectations using topics related to our environment. Resources supporting environmental issues are readily available on line in the form of articles, videos, and speeches. In addition, students can gather relevant data through outdoor learning experiences, a unique benefit to this content area. Teachers can structure rich and relevant investigations that mirror performance tasks on the new assessments, using the environment as a context for learning.

Designing a Performance Task

Let’s visit a grade three elementary classroom where the children have been studying the life cycle of the salmon including how to preserve and protect water quality and quantity so that salmon can continue to survive. After visiting a local fish hatchery, the students illustrate the life stages of salmon, monitor their own water consumption, and create a rule that they can enact at school to preserve and protect water. In addition, they visit a local creek to view the salmon first hand, appreciating their beauty and endurance. How might the Common Core ELA standards support the learning in this unit? What might students research, what issue might they weigh in on, and what product might they create—an essay or a speech?

The new performance assessments are designed to measure proficiency in reading, writing, research and speaking and listening. The students are given a scenario that is grounded in a real world context. Then they acquire knowledge of the topic or issue by reading pre- selected articles and watching chosen videos. The students are expected to take notes on the information provided, keeping in mind the task that they are given in the scenario.

Here’s how this might play out in our elementary classroom. The students are provided with this scenario:

You have been asked to explain why salmon need clean water to survive. You will read an article and watch a video that provides you with information about the needs of salmon for their survival. You will take notes on the articles and the video, writing an informational essay explaining why salmon need clean water to survive.

Students read the article provided, preferably on the computer since all of the new assessments will be delivered using technology. Students will work in an entirely online environment so must learn how to navigate websites, read material on a computer screen, and compose their essays using a keyboard. For our hypothetical Salmon task, reading and viewing material might include the following:

Article #1: Short piece explaining the salmon’s need for clean water. Video #1: Showing pollution in our waters and its effects on salmon.

Scoring Performance Tasks: Research Skills and Writing Rubrics

All performance tasks include research questions that require the students to draw information from the multiple sources in preparation for writing an essay or speech. These questions are measuring specific research skills.

The research skills include the following:

- The ability to locate information

- The ability to select the best information including distinguishing relevant from irrelevant information and facts from opinions.

- The ability to provide sufficient evidence to support opinions expressed

Rubrics are provided for each of the three skills and are used for scoring student responses.

Here are some example research questions that link to our salmon task:

According to the video, what are two important steps we can take to preserve and protect our salmon? Use details from the video to support your answer. (Locating Information)

Which source, the video or the article, best helps you understand the needs of salmon? Use details from both sources to support your answer. (Selecting the best information)

Based on the reading and the video, what do you think is the one most important thing we could do to protect our salmon? Use details from both sources to support your answer. (Using sufficient evidence)

Students write their responses to the research questions using the notes that they have taken while reading the article or viewing the video. They submit their answers for scoring and on a second day, proceed to part two of the assessment.

Part two involves writing an essay or outlining and delivering a speech. The Common Core ELA requires that students be skilled in their ability to write in three different modes: informative/explanatory, opinion/argumentative, and narrative.

Students must also be able to outline and deliver a speech on a given topic. In our elementary grades salmon task example, students might be given the following prompt:

You have been asked to write an informational essay where you share what salmon need to survive. Use information from both the article and the video to support your ideas.

To demonstrate the CC ELA writing standards, students must use information from the various sources, clearly summarizing their information with text-based evidence.

Background knowledge is not a factor when scoring these essays. Students must cite text-based evidence to support their ideas, not prior knowledge from other sources. Essays are scored using a five trait rubric. Close reading of text is paramount in the ELA CC standards.

Scenario-Based Problems

Performance tasks require students to engage with a scenario-based problem, research information presented in various media, extract key ideas from the information, answer research questions, and compose an essay or speech that presents their original opinions and ideas supported by text based evidence. Task developers follow a specific template when creating performance assessments. The template includes identifying a plausible scenario, locating appropriate source material, designing research questions and structuring an essay or speech that synthesizes information from the research.

Selecting the content for these tasks is critical for the content must be relevant and problem based. Students practice and apply career and college ready skills including critical thinking and analysis. Topics connected to the environment provide real-world scenarios that can capture the interests of our students.

Here are some examples of Environment focused Performance Tasks that the Pacific Education Institute has developed for K-12 teachers to assign to their students:

Healthy Waters: How do water treatment plants work and why are they important?

SOS: Saving Our Sound: What can we do to improve the health of the Puget Sound?

Stormwater Engineering: How do engineers solve problems linked to storm water runoff?

Earth Day: What is the history behind the environmental movement and how has this movement influenced legislation today?

Ocean Acidification: What can we do to ensure the survival of our shellfish?

Field Experiences and Performance Tasks

Field experiences, an important component of environmental education, can be part of a performance assessments, either embedded in the assessment itself or as a follow up activity. Students can enhance their knowledge acquired through text-based research with knowledge gained in a systematic way through direct experience. Scenarios may be developed that incorporate outdoor learning experiences where students reinforce their understanding of the topic provided through direct observation and data gathering. In our salmon example, students could be prompted to take pictures on their field experiences to the fish hatchery and to the local stream, providing visual images of the salmon to support their text-based evidence. These photos can serve as primary source material when students compose their essays or outline their speeches.

Much has been written and created regarding sustainability issues. Teachers can select a topic appropriate to their grade level curriculum and locality, compose a scenario that is directly relevant to the student, and identify source material for student engagement. They can also incorporate outdoor learning experiences that enhance understanding, promote enthusiasm for the environment, and add to their knowledge base. By designing performance tasks using the environment as the context for learning, students work with relevant information, learn about the challenges we face, and form opinions at a young age that will guide their future thinking and civic involvement.

Democracies, for their survival, demand an informed electorate. Environmental issues may be the most critical issues our children will face. We can accomplish two important goals by linking performance assessments to sustainability education. One goal is to teach and practice the ELA skills that the students will need to be career and college ready. The second and equally important goal is the ability to form reasoned judgments about environmental issues. By connecting the Common Core ELA standards to the environment, students benefit on two fronts: Acquiring both environmental literacy and literacy in English Language Arts.

Our children face crucial decisions regarding a sustainable future. Their knowledge base, critical thinking skills, and ability to effectively communicate are keys to informed decision-making. We must educate our children to effectively read, write, research, speak and listen. They need to think critically and creatively in order to solve the complex problems we face.

Let’s make content choices for our curriculum that are meaningful today and into the future. Nothing is more relevant, engaging, and crucial than issues related to preserving and protecting our environment.

Nancy Skerritt is an educational consultant after 22 years as a classroom teacher in the Tahoma School District in Washington.

Nancy Skerritt is an educational consultant after 22 years as a classroom teacher in the Tahoma School District in Washington.

Margaret Tudor is the founder and director of Pacific Education Institute.

by editor | Sep 2, 2025 | At-risk Youth, Environmental Literacy, Equity and Inclusion, Learning Theory, Service learning

Developing the “Whole Person”

By Emily J. Anderson

Photos by Emily McDonald-Williams

Practitioners in the field of environmental education have a variety of personal reasons for pursuing this work. Many cite their desire to connect youth with nature, introduce youth to careers in the sciences, and generally, create an environmentally literate society. While we are deeply focused on these goals, there may be even more compelling outcomes under the surface. Environmental educators are creating successful, healthy, contributing members of society. In other words, we are supporting “whole-person development” through our rich educational programs.

While environmental educators may recognize these broader impacts on the youth they serve, we rarely design our programs to support positive youth development outcomes with intentionality. Nor do we measure these outcomes through evaluation and assessment. Rather, we are often highly focused on learning outcomes and meeting science standards. Designing environmental education programs within a research-based positive youth development framework and then measuring outcomes, not only adds tremendous meaning to our efforts, but also adds credibility and value to our field. If we begin thinking of ourselves as positive youth development educators, in addition to content specialists, our program outcomes expand, leading to greater organizational growth.

Positive Youth Development, or PYD, emphasizes building on youth’s strengths, rather than on the prevention of problems. Meaning, programs seek not only to prevent adolescents from engaging in health-compromising behaviors, but also to build their abilities and competencies (Roth & Brooks-Gunn, 2003). This approach suggests empowering youth in their own development through relationships with peers, mentors, family, school, and community. The research supports the importance and power of a holistic approach to youth development, comprehensively infusing youth programs with core PYD elements. These include opportunities for belonging, opportunities to make a difference, supportive relationships, positive social norms, opportunities for skill building, and integration with family, school, and community efforts (Sibthrop, 2010).

Case Study: Designing and Evaluating

4-H Junior Master Naturalist”

4-H is the nation’s largest youth organization with a long history of positive outcomes. One of the many characteristics that makes 4-H unique and adds to its strong reputation is that its programs are deeply rooted in positive youth development (PYD) theory. One of 4-H’s mission mandates is science and there are countless environmental education programs that fall under that umbrella. One such program is Oregon’s Junior Master Naturalist. As with other 4-H programs, Junior Master Naturalist was intentionally designed within a positive youth development framework: the Oregon 4-H Program Model. To measure the success of this design, participants completed evaluations for both environmental literacy outcomes and PYD outcomes. Junior Master Naturalist serves as a worthy example of situating environmental education programming within a PYD context.

Junior Master Naturalist is an experiential, place-based, science program. It targets underserved youth through after-school and weekend sessions as well as a four-day residential camp experience. Participants engage in six units of study: ecoregions, geology and soils, watersheds and water resources, forests and plant communities, wildlife, and marine science. Approximately 75% of experiences are field based, while 25% are hands-on classroom activities. All sessions are family-friendly and content is often youth-driven.

The goals of Junior Master Naturalist are to connect youth with their local landscape, develop a sense of stewardship, introduce participants to natural science careers, and improve environmental literacy. Additionally, following the Oregon 4-H Program Model, developmental outcomes sought are academic motivation and success, reduction in risk behaviors, healthful choices, social competence, personal standards, and connection and contribution to others.

Content goals for Junior master Naturalist are achieved through curriculum design and field experiences. However, developmental outcomes required consideration of several programmatic factors. These include 1) high program quality, 2) appropriate intensity and duration, and 3) healthy developmental relationships. It was important to program staff to ensure that not only would the curriculum and activities be of high quality, but the opportunity for youth to connect with one another and have positive adult role models were present as well. Furthermore, participants have the opportunity to pursue deeper study of topics they most connect with and are offered a wide range of field experiences, including camping, citizen science, service learning, and outdoor recreation. There is a continual focus on health and well-being, independent exploration, and making connections to their local communities.

In 2017, participants from three Junior Master Naturalist cohorts completed evaluations measuring several desired outcomes. The evaluation tool first asked participants to rate their feelings about their interest in science, their perceived competency in science, their interest in a science career field, and their desire to learn more about science. As anticipated, results demonstrated growth in all areas. Next, the evaluation measured positive youth development outcomes based on the framework used in program design.

Indicators of program quality included participants’ sense of belonging in the program.

94.9% reported feeling welcome

96.1% said they felt safe

90.9% said they felt like they mattered

Measuring the presence of developmental relationships included adults in the program expressing care, challenging growth, and sharing power.

98.6% felt respected by adults in the program

94.9% said adults paid attention to them

92.9% believe adults expected them to do something positive

While this is only a snapshot of PYD evaluation results from the Junior Master Naturalist program, it illustrates the tremendous potential of measuring and sharing the developmental outcomes achieved in environmental education programs.

Integrating Positive Youth Development in Your Program

Integrating Positive Youth Development in Your Program

One of the fortuitous qualities about environmental education programs is that short- and long-term developmental outcomes inherently occur whether we are intentional about positive youth development, or not. However, if you want to get more out of your program, challenge yourself to incorporate PYD principles during the planning phase of your program. Alternatively, for existing programs, consider self-evaluating with a proven PYD framework to identify gaps and opportunities for improvement.

The Oregon 4-H Program Model is a framework specifically designed for 4-H programs. However, there are other prominent models with broader application for use in a variety of youth programs. These include The Five Cs, Community Action Framework for Youth Development, and Character Counts!. According to experts in the field, however, the Developmental Assets Framework is likely to remain among the most useful approaches to positive youth development for the near future. The scientific depth and practical utility of this model provide extensive resources for assessment, planning, implementation, and evaluation for programs serving youth and communities in a variety of settings (Arnold & Silliman, 2017).

The Developmental Assets Framework, developed in 1990 by the Search Institute, identifies a set of skills, experiences, relationships, and behaviors that enable young people to develop into successful and contributing adults. According to research, the more Developmental Assets young people acquire, the better their chances of succeeding in school and becoming happy, healthy, and contributing members of their communities and society. The list of 40 Developmental Assets for Adolescents, broken down by age groups, can be found on the Search Institute’s website (Search Institute, 2017)

Becoming familiar with the Developmental Assets and thinking about how you can support this development in your program’s participants is the first step to infusing a healthy layer of positive youth development in your program. Digging in to the research and consulting experts in the field will help to identify the best way to integrate PYD principles and design evaluation instruments that measure effectiveness. Perhaps starting by including several PYD questions in your existing participant evaluation will provide valuable baseline data to inform growth potential.

In summary, environmental educators are doing noble work with endless benefits for youth, ecological systems, and our society as a whole. It is important that we recognize the value in our work that often goes unseen and celebrate our, often, hidden successes. Youth in our programs are building confidence and independence, developing healthy lifestyles and pro-social behaviors, and becoming contributing members of their communities. While these victories are already something to be proud of, why not take it up a notch by putting some intentionality behind our efforts to reach even greater outcomes? While designing high quality environmental education, we should challenge ourselves to support development of the “whole person” by incorporating positive youth development principles. Not only will these efforts have lifelong impacts on our program participants, but they will support our organizations as well. Sharing evidence of positive developmental outcomes will help promote our programs, recruit more participants, and appeal to potential funders for increased financial support. ❏

References

Arnold, M.E. & Silliman, B. (2017). From theory to practice: a critical review of positive youth development program frameworks. Journal of Youth Development, 12(2), 1-20.

Roth, J. L., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2003). What exactly is a youth development program? Answers from research and practice. Applied Developmental Science, 7, 94-111.

Search Institute, (2017). Developmental assets. Retrieved from http://www.search-institute.org/research/developmental-assets

Sibthrop, J. (2010). A letter from the editor: Positioning outdoor and adventure programs within positive youth development. Journal of Experiential Education, 33(2), vi-ix.

Emily Anderson is a 4-H Youth Development Educator in Lane County, Oregon. She has written previously for CLEARING.

It is a warm summer day at Silver Falls State Park and a group of teachers are conducting a macroinvertebrate study on the abundance and richness of species around the swimming hole. The air is filled with sounds of laughter from children playing, parents conversing on the bank, and the gentle babble of the stream below the dam. The teachers, armed with Dnets, clipboards, and other sampling equipment, move purposefully through the water collecting aquatic species. Being a leader at this unique workshop, I am there to support the teacher’s inquiry project and also help brainstorm ways to bring this type of work back to their classrooms.

It is a warm summer day at Silver Falls State Park and a group of teachers are conducting a macroinvertebrate study on the abundance and richness of species around the swimming hole. The air is filled with sounds of laughter from children playing, parents conversing on the bank, and the gentle babble of the stream below the dam. The teachers, armed with Dnets, clipboards, and other sampling equipment, move purposefully through the water collecting aquatic species. Being a leader at this unique workshop, I am there to support the teacher’s inquiry project and also help brainstorm ways to bring this type of work back to their classrooms. Teachers often want to backwards plan, knowing the end product their students will experience and learn. But this type of scientific inquiry requires us to let go of control so that students can ask authentic, meaningful questions that are not yet answered. Teachers come to learn that teaching the process of science is often more valuable than teaching the content. They are engaging in the work of true scientists and learning how to be curious, lifelong learners along the way. Being a part of inspiring projects and trips such as these is an experience that teachers, students, and even parent volunteers will remember for years to come. As an upper elementary teacher myself, I often hear about the power of our work when families come back to visit and reminisce about their time in my classroom. I know that this work will impact future generations and their enthusiasm for science learning. Not only that, we are teaching students to do, read and understand the work of a scientist so they can make informed choices in their adult lives.

Teachers often want to backwards plan, knowing the end product their students will experience and learn. But this type of scientific inquiry requires us to let go of control so that students can ask authentic, meaningful questions that are not yet answered. Teachers come to learn that teaching the process of science is often more valuable than teaching the content. They are engaging in the work of true scientists and learning how to be curious, lifelong learners along the way. Being a part of inspiring projects and trips such as these is an experience that teachers, students, and even parent volunteers will remember for years to come. As an upper elementary teacher myself, I often hear about the power of our work when families come back to visit and reminisce about their time in my classroom. I know that this work will impact future generations and their enthusiasm for science learning. Not only that, we are teaching students to do, read and understand the work of a scientist so they can make informed choices in their adult lives. Tina Allahverdian is passionate about connecting students with science in the natural world. When not teaching fifth graders, she can be found reading in a hammock, kayaking through Pacific Northwest waters, or hiking in the mountains. She currently teaches in West Linn, Oregon, and resides in SE Portland with her husband, twin boys, and their dog, Nalu.

Tina Allahverdian is passionate about connecting students with science in the natural world. When not teaching fifth graders, she can be found reading in a hammock, kayaking through Pacific Northwest waters, or hiking in the mountains. She currently teaches in West Linn, Oregon, and resides in SE Portland with her husband, twin boys, and their dog, Nalu.

Integrating Positive Youth Development in Your Program

Integrating Positive Youth Development in Your Program