by editor | Sep 1, 2025 | Conservation & Sustainability, Equity and Inclusion, Indigenous Peoples & Traditional Ecological Knowledge, K-12 Classroom Resources, Tribes & Traditional Ecological Knowledge

Indigenous Perspectives on EE

Summer 2022

These are exciting times in our region. We are fortunate to live at the confluence of two currents: the growing integration of Indigenous perspectives in both formal and informal education, and a surge of cultural revitalization in Indigenous communities. In the state of Washington, the 2015 passage of Senate Bill 5433 requires public K-12 schools to teach Indigenous history, culture and sovereignty in collaboration with the tribes nearest their schools. Educators have a rich variety of curricular materials to draw upon, beginning with the Since Time Immemorial curriculum. In the state of Oregon, the 2017 passage of Senate Bill 13 Tribal History/Shared History has led to similar developments in curriculum creation and collaboration between schools and tribes. Simultaneously, Indigenous communities around the region are experiencing a dramatic and wide-ranging cultural resurgence, including language revitalization and the revival of traditional pre-colonial practices. This fertile convergence offers a wealth of new opportunities to both Indigenous and non-Indigenous educators and their students. This special edition’s essays, including contributions by both Indigenous and non-Indigenous practitioners, introduce you to these currents and opportunities by focusing on Indigenous relationships with the more-than-human world, and particularly our ties to our plant relatives. We hope that these essays will inspire and guide you as you explore ways to enhance your teaching by accurately and respectfully integrating Indigenous experience and knowledge.

—Rob Efird and Laura Lynn

Co-editors

by editor | Jan 16, 2024 | Environmental Literacy, IslandWood, K-12 Activities, K-12 Classroom Resources, Learning Theory

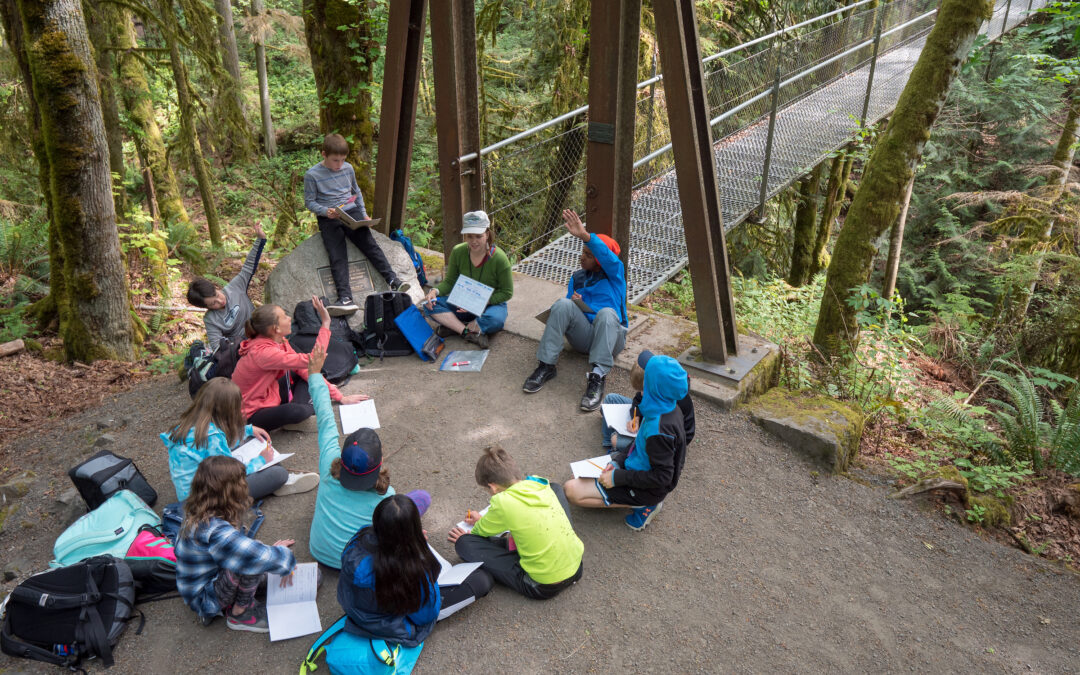

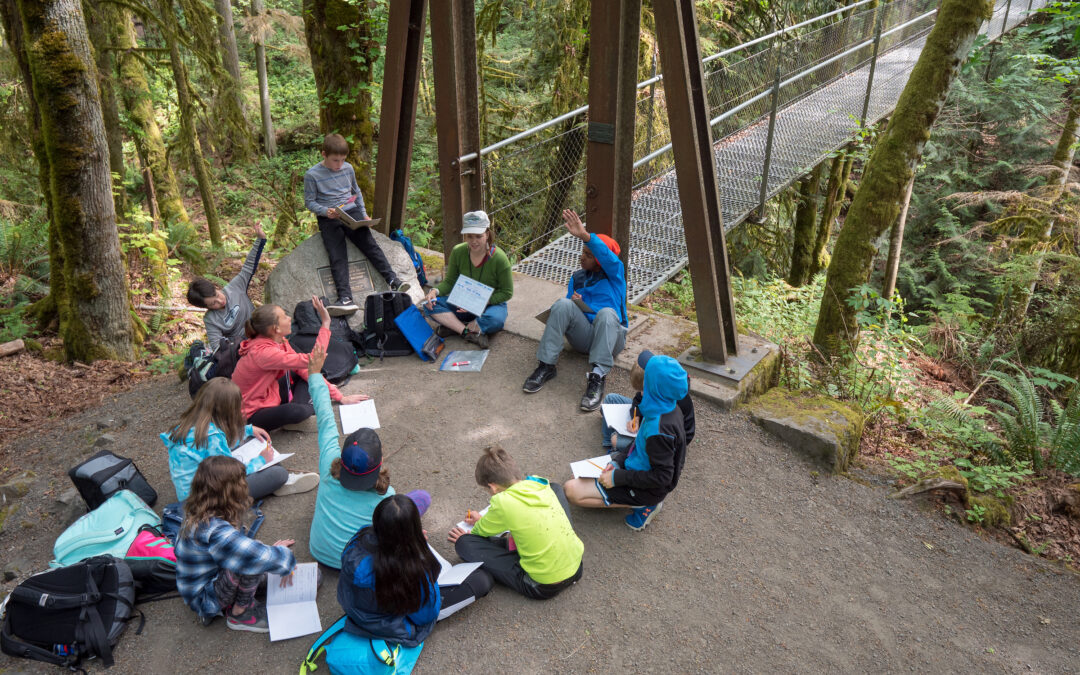

by Zachary Zimmerman

Bainbridge Island, WA

s an outdoor educator, I often get sucked into the false binary that lessons are either fun or informative, that content must be sweetened with games, stories, and activities like applesauce for children’s medicine. But stories are one of the oldest forms of teaching known to humankind, and games and interactive activities help students interpret and internalize what they learn on trails, in classrooms, and at home. In this article, I invite you to stop apologizing for your content teaching and start weaving it into lesson sequences that include stories, games, writing activities, and more. Sequences can make your teaching practices more effective, more equitable, and yes, more fun.

s an outdoor educator, I often get sucked into the false binary that lessons are either fun or informative, that content must be sweetened with games, stories, and activities like applesauce for children’s medicine. But stories are one of the oldest forms of teaching known to humankind, and games and interactive activities help students interpret and internalize what they learn on trails, in classrooms, and at home. In this article, I invite you to stop apologizing for your content teaching and start weaving it into lesson sequences that include stories, games, writing activities, and more. Sequences can make your teaching practices more effective, more equitable, and yes, more fun.

Recently, I learned that teachers visiting Islandwood with their students were passing on the same feedback week after week: many of the lessons our instructors were teaching on ecosystems fell short because students didn’t fully understand what the word “ecosystem” meant. They might be able to give examples (“rainforest”) or describe them somewhat (“habitat”), but they were missing the definition and significance: communities of different living things that interact with each other and their physical habitats. An ecosystem isn’t just a place; it’s a dynamic arrangement of matter and energy; sunlight, water, and nutrients; life, death, and life again. Of course it needs some scaffolding

Because ecosystems are one of my favorite things to teach 5th graders, I took note immediately. Learning about ecosystems helps students understand the world in which they live, sets the stage for deeper sense-making outdoors, and aligns neatly with NGSS standards and cross-cutting concepts. Ecosystems are also teachers themselves, offering lessons on diversity, interdependence, resilience, and identity. When students see forests and intertidal zones as neighborhoods full of unique and diverse beings supporting each other through their mere existence, they may have an easier time valuing their own identities and thinking more about how they fit into their communities. To restate ecologically, they may discover their own niche.

As heady and enticing as these ideas are to me, I know that teaching for equity means letting go of preconceived notions of how students will use my lessons, and creating space and support for them to connect ideas presented in class to their own lives. It also means ensuring that all students are working from the same baseline of knowledge as they explore those more abstract spaces. In the past, I had equated “baseline” with “lecturing” and “lecturing” with “boring”, leading me to approach core content apologetically and half-heartedly.

To address my reluctance and reimagine content teaching as a part of, not apart from, the immersive fun and exploration that drew me to outdoor education, I started experimenting with lesson sequencing: using stories, activities, and games to bookend and contextualize core concepts. What started as an apologetic approach to content has proven an effective and equitable strategy for outdoor teaching that makes complex ideas like ecosystems meaningful, memorable, and fun. Below I outline a favorite lesson sequence on ecosystems that envelopes content with storytelling and modeling activities. But first, a few tips for developing your own sequences.

Work Backwards

Mapping the core concepts you need to scaffold into a larger lesson can reveal where your content time will best be spent. In the ecosystem example below, I use worksheets to get all my students on the same page about producers, consumers, and decomposers: what they are, what they need, and how they relate to each other. Knowing which concepts I need to teach about can also help me select starting lessons that introduce relevant terms or relationships.

Know Your Audience

Are your students quiet or chatty? Do they like individual reflections, pair-shares, or large group discussions? Maybe a combination? Do they ask a lot of questions, or wait for you to give answers? Do any of your students have IEPs or 504 plans? What other accommodations might one or many students need to feel safe, comfortable, and ready to learn and participate? Consider these questions when thinking about your group and reflect on how they might impact your plan. Maybe you need to switch out that starting story for a running game; maybe that running game works equally well walking or sitting.

Find Your Flow

Once you know what information, structure, and supports your students need to reach their learning targets, think about an order of operations that makes sense for the spaces you’ll be teaching, your style, and the energy you expect. Thinking about biorhythms can be a helpful clue here – if you’re starting this module right after lunch, will students be more or less active than if you began your morning with it? There’s no perfect formula here, but Ben Greenwood’s Lesson Arc (Introduction, Exploration, Consolidation) provides helpful inspiration. Personally, I like to start with something engaging that models the ideas we’ll use and end with a game or reflective activity – again, this is where art meets science, so get creative.

Now that you have some ideas for sequencing lessons, let’s look at an example.

Lesson Sequence: Ecosystems and Interdependence

Materials:

- Storybook

- Ecosystem worksheets (Islandwood journal is used in this example)

- Ecosystem cards (make your own or find publicly available regional sets like this one from Sierra Club British Columbia)

- Ball of string or twine

- Writing untensils

Lesson 1: Read The Salamander Room by Anne Mazer (read-along here

This is the story of a young boy who brings home a salamander to live in his room. As his mother continues to inquire about how the boy will care for the salamander (and eventually, to care for everything else he has added to his room in the process), students begin to see not only how different living things rely on each other, but the impacts of removing a more-than-human friend from its chosen home.

Additional discussion questions:

- How did the room change throughout the story?

- What else would you have changed?

- What relationships did you notice?

(Of course, any storybook of your choosing that describes habitats, food webs, nutrient/energy cycles, and interconnectivity will work – I just like this one!).

Lesson 2: Ecosystem Components and Definitions

Transitioning into the content component, begin by asking students if they have ever heard of the word “ecosystem” and what it means. While assessing answers, ask whether they saw an ecosystem in the story they heard. These discussions can help decenter the instructor as the holder of knowledge and assess potential leaders in your group.

Next, pass out worksheets/journals and give students 5-10 minutes to complete the assigned pages, encouraging them to quietly work alone or in small groups. Set clear expectations that they should do their best to fill out whatever they know, and that we’ll fill them out together as a group afterward.

Drawings from a student’s Islandwood journal. Mushrooms are depicted as decomposers, trees as producers, and squirrels as consumers. On the next page, sentence and word starters help students decode core definitions.

When students indicate that they are done, invite them back to a large group. Ask if anyone can give definitions of producers, consumers, and decomposers, or share examples that they drew or wrote in their journals. This helps individual students confirm or correct their answers without judgment and add test their knowledge by adding their own examples to the discussion. Talking through producer growth, animal consumption, and decomposition a few times helps reinforce how different inputs and outputs relate to the process and emphasizes its cyclical nature.

When students have completed their worksheets and all questions have been answered, move on to Lesson 3.

Lesson 3: Web of Life (adapted from Sierra Club British Columbia)

Because a full lesson plan is linked above, I focus here on ways that I consolidate knowledge from the above lessons, assess content learning, and prepare students to apply these new ideas to future exploration.

Pass out Web of Life cards to your students and save one for yourself. If you plan to introduce a new element later (e.g. birds migrating from habitat loss or new trees planted by conservationists), hold onto those cards.

As you pass out cards, ask students to take a moment and acquaint themselves with their element. Some questions you might ask:

- Are they a producer, decomposer, consumer, or something abiotic?

- What do they know about this element?

- What does this element need to thrive?

- What threatens it?

When students are ready, begin the lesson as described in the linked plan. Empower students to help correct or add to others’ ideas. For example, if a student assigned “worm” passes to “soil” and says, “I relat to soil because I eat it,” invite the group to discuss what they know about how worms relate to soil or how they get their energy (i.e. decomposition, which makes soil).

Once the web is fully developed, you can take this lesson in many directions, inviting students to consider what happens when one part of the web is removed or changed. When they can see that everything is connected, even indirectly, you’re ready to explore ecosystems!

Zachary Zimmerman (he/him) is an outdoor educator, teacher training facilitator, and insatiable problem-solver residing on the traditional Suquamish/Coast Salish land currently known as Bainbridge Island

Sources Cited

5-LS2-1 Ecosystems: Interactions, Energy, and Dynamics | Next Generation Science Standards. (n.d.). Retrieved May 25, 2023, from https://www.nextgenscience.org/pe/5-ls2-1-ecosystems-interactions-energy-and-dynamics

Greenwood, B. (n.d.). What is Lesson Sequencing and How Can it Save You Time? Retrieved May 25, 2023, from https://blog.teamsatchel.com/what-is-lesson-sequencing-and-how-can-it-save-you-time

Mazer, Anne., & Johnson, S. (1994). The Salamander Room (1st Dragonfly Books ed.). Knopf

Sierra Club BC. (n.d.). Web of Life. Sierra Club BC. Retrieved May 25, 2023, from https://sierraclub.bc.ca/wp-content/uploads/Web-of-Life-Game.pdf

by editor | Jul 20, 2021 | K-12 Classroom Resources

by editor | Aug 13, 2018 | K-12 Classroom Resources, Place-based Education

Enlivening Students

by Gregory A. Smith

Review of Sarah Anderson’s, Bringing School to Life: Place-Based Education across the Curriculum (Lanham, Massachusetts: Rowman & Littlefield, 2017)

or the past two decades, books and articles written by place- and community-based advocates have been largely focused on defining and justifying an alternative approach to teaching and learning grounded in local knowledge and issues with the aim of inducting children into a sense of community participation and responsibility. This literature was largely exhortatory rather than prescriptive. It did not often provide interested teachers with detailed guidelines about how to move from a broad vision to the challenge of creating and enacting curriculum and instruction not limited by either textbooks or even classrooms. These advocates asked teachers to be courageous and take risks, trusting in their capacity to experiment and learn from their failures and successes. And many teachers across the United States and elsewhere became early adopters of this approach, willing to embrace those challenges and risks. As place- and community-based education enters its third decade, however, something more is needed to make its implementation appealing and understandable to a broader group of educators. Sarah Anderson’s Bringing School to Life: Place-Based Education across the Curriculum (2017) provides exactly the kind of guidance required to accomplish this end.

or the past two decades, books and articles written by place- and community-based advocates have been largely focused on defining and justifying an alternative approach to teaching and learning grounded in local knowledge and issues with the aim of inducting children into a sense of community participation and responsibility. This literature was largely exhortatory rather than prescriptive. It did not often provide interested teachers with detailed guidelines about how to move from a broad vision to the challenge of creating and enacting curriculum and instruction not limited by either textbooks or even classrooms. These advocates asked teachers to be courageous and take risks, trusting in their capacity to experiment and learn from their failures and successes. And many teachers across the United States and elsewhere became early adopters of this approach, willing to embrace those challenges and risks. As place- and community-based education enters its third decade, however, something more is needed to make its implementation appealing and understandable to a broader group of educators. Sarah Anderson’s Bringing School to Life: Place-Based Education across the Curriculum (2017) provides exactly the kind of guidance required to accomplish this end.

Anderson is a former student of David Sobel, one of the early advocates of this approach. For the past dozen years she has embraced what she learned while studying with him first as a middle-school teacher and now as the fieldwork coordinator at the Cottonwood School of Civics and Science in Portland, Oregon. Anderson’s work is especially powerful because of her concern about citizenship education and democratic practice. Place-based educators often focus primarily on providing students with immersive experiences in nature without necessarily engaging them in the cultural understandings, conflicts, problem-solving, and negotiation that accompany life in civil society. This is not to diminish the importance of those immersive experiences—which can be central to the development of a strong environmental ethic—but in themselves not enough to give young people the confidence or savvy required to become engaged community actors. Anderson’s work exemplifies how this can happen and how schools and communities can truly “get better together.”1

Her volume provides multiple examples of lessons and units she or the teachers she works with have developed and taught. Chapters describe ways that students can use maps to learn about their place, contribute to its human and environmental health through community science, learn directly about local history, partner with nearby agencies and organizations, explore the way different subject areas can be integrated to deepen knowledge and understanding, and develop a sense of connection with and empathy for one another and people beyond the school. The three chapters about mapping, citizen science, and local history provide detailed descriptions of units interested but uncertain teachers could profit from as they begin to incorporate local possibilities into their own work with students; they will be the focus of the remainder of this review.

Maps offer not only a good way to introduce children to their own place but to think about “What is where, why there, why care?”2 They naturally lead students to observe, collect data, and make inferences. At the Cottonwood School maps are integrated into the learning experiences of children at all grade levels. Early in the school year as a welcoming activity, everyone is invited to create and share personal maps of things special to them in their bedroom, home, neighborhood, or someplace away from home. Kindergarteners through second graders then create maps of their classroom and playground, sometimes using blocks and unix cubes to illustrate a space. Third graders map the school focusing on specific features such as sound. Fourth through sixth graders create maps to scale of neighborhood features such as parks and then compare and contrast in writing the data presented in their maps. Sixth graders map nearby features of their own choosing. They walk through the South Waterfront neighborhood and record the location of things like K9 restrooms (fire hydrants), bike racks, and food carts. They then create a formal illustrated map with compass roses and borders (and sometimes sea serpents in the Willamette River) to represent what they have found. Seventh and eighth graders go further afield and focus on the city and state. Given a map of the city’s boundaries and different districts, they identify major bodies of water, traffic routes, and one personally significant place in each district. This leads into a more extensive exercise in which they choose one data set to map. Possibilities include population, temperature levels during a heat wave, city parks, or the location of Starbucks coffee shops. They are encouraged to think about who has access to which resources by comparing demographic maps that focus on race and ethnicity. Maps offer a way to synthesize disparate but related information as well as integrate a variety of subject matter.

The school’s incorporation of community science offers similar opportunities to link lessons to students’ lives and create learning experiences that allow for observation, analysis, and curricular integration. Community science involves identifying local phenomena or issues worthy of study and action and linking these topics to the Next Generation Science Standards. One year, seventh- and eighth-graders identified the problem of animal waste in the neighborhood as an issue they wanted to explore and investigate. As they ventured beyond the school for a variety of learning activities, they found nearby sidewalks both hazardous and smelly. They decided to do something about it. Their teacher divided the class into teams who performed different tasks: one counted all of the pet waste in a six-block radius, another researched the environmental toxins found in dog poop, a third team investigated Portland laws regarding the regulation of pet waste, and a fourth researched similar laws in other cities. Once students had all of this information in hand, they analyzed what they had found and brainstormed possible solutions. They then wrote letters to public officials recommending that the city provide more public education about this problem and enact bigger fines for people who violated laws already on the books. Their letters resulted in a meeting with officials in city hall, and their ideas were incorporated into a “petiquette” campaign that the city had already begun planning. Extended units like these offers students a chance to systematically explore a topic, do so in ways that allow them to see its relevance to their own lives, and then make a contribution to the broader community. Such experiences match the call by framers of the NGSS to apply scientific concepts and practices to real life circumstances.

One of Anderson’s talents lies in her capacity to find ways to make the study of history local, as well. The third grade curriculum, for example, includes a focus on Native Americans. As part of that study, students visited the Oregon Historical Society, Portland State University’s Department of Archeology, and a traditional Chinook longhouse at Ridgefield, a National Wildlife Refuge in Washington State less than an hour from the city. Returning to the school, they transformed their classroom into a longhouse with a “fire pit” in the middle of the room. They also participated in PSU’s Archeology Roadshow where after having learned about the characteristics of meaningful exhibits at the Oregon Museum of Science Industry, they created a longhouse model and became the only K-12 students to share their work at an event otherwise populated with much older presenters. The opportunity to be involved with people beyond the school at PSU or City Hall demonstrates to children that they are as much citizens as anyone else in their community, lending them both a level of confidence and a sense of responsibility too absent in the education of this country’s future adults.

Learning experiences like these are deeply engaging for students. Furthermore, they demonstrate to community members the capacity of children to make genuine contributions to their common life. Anderson’s book offers a useful and inspiring roadmap for other educators interested in realizing this vision of place-based education themselves.

NOTES:

1 Tagline for the Rural School and Community Trust, an organization that grew out of the Annenberg Rural Challenge, the first national effort in the 1990s aimed at disseminating the possibilities of place-based education.

2 In Brian Baskerville’s 2013 article, “Becoming Geographers: An Interview about Geography with Geographer Dr. Charles Gritzner (http://geography.about.com/od/historyofgeographty/fl/Becoming-Geographers.htm).

____________________________________________________________________________

Gregory Smith is a professor emeritus of the Graduate School of Education and Counseling at Lewis & Clark College in Portland, Oregon. He has written numerous articles and books about environmental and place- and community-based education. He is a fellow of the National Education Policy Center at UC-Boulder, a member of the education advisory committee of the Teton Science Schools, and a board member of the Cottonwood School of Civics and Science.

Gregory Smith is a professor emeritus of the Graduate School of Education and Counseling at Lewis & Clark College in Portland, Oregon. He has written numerous articles and books about environmental and place- and community-based education. He is a fellow of the National Education Policy Center at UC-Boulder, a member of the education advisory committee of the Teton Science Schools, and a board member of the Cottonwood School of Civics and Science.

by editor | Feb 22, 2017 | K-12 Classroom Resources

News release submission for CLEARING Magazine – February 2017

The Garden of Wisdom

A peace-building program among environmental educators and conservationists in the Middle East inspires children to love and nurture the natural world. Please help us to publish our first book, The Garden of Wisdom: Middle Eastern Stories for Environmental Stewardship.

s professionals who care passionately about the world around us, environmental educators are living through some challenging times. Now there is good news about something real that you can do to help bring about positive change in a troubled region while fostering a deep connection between children and nature. In recognition of its promise to transform the lives of many people, this project has been awarded the National Storytelling Network’s prestigious Brimstone Award for Applied Storytelling. Your contribution will help us to promote environmental awareness and peaceful coexistence in the Middle East—one person, one organization and one story at a time.

s professionals who care passionately about the world around us, environmental educators are living through some challenging times. Now there is good news about something real that you can do to help bring about positive change in a troubled region while fostering a deep connection between children and nature. In recognition of its promise to transform the lives of many people, this project has been awarded the National Storytelling Network’s prestigious Brimstone Award for Applied Storytelling. Your contribution will help us to promote environmental awareness and peaceful coexistence in the Middle East—one person, one organization and one story at a time.

https://shinefund.org/funds/96

For the past ten years, environmental educator Michael J. Caduto—co-author of the award-winning Keepers of the Earth® series of books and author of Earth Tales from Around the World and Catch the Wind Harness the Sun—has been directing an environmental education and storytelling project in the Middle East. The Stories for Environmental Stewardship Program involves more than 50 individuals and 20 organizations from Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon and Palestine. This courageous community of professionals shares a passion for conservation and for encouraging children to understand and cherish the natural world.

The Stories for Environmental Stewardship Program is now ready to publish its first book: The Garden of Wisdom: Middle Eastern Stories for Environmental Stewardship. Artists and photographers from the Middle East are illustrating this anthology of children’s stories. This book will also become a steppingstone to an environmental education curriculum that reveals how nature is the root of a shared connection to the land that binds all peoples as one.

With your support this new book can bear fruit. Once the book is published, proceeds will be used to offer books and small grants that support the work of environmental education and conservation organizations from throughout the region. Please visit the Garden of Wisdom campaign at the following web page to watch the video and find out how you can help to make it possible to publish these inspiring stories:

https://shinefund.org/funds/96

Thank you!

Contact:

Michael Caduto

Email: michaelcaduto@p-e-a-c-e.net

Phone: 802-484-3484

by editor | Nov 20, 2014 | K-12 Classroom Resources, Outdoor education and Outdoor School

Early literacy skills can be developed and enhanced through journaling and data collection. Even the youngest learners can feel successful.

Effective Education: Turning the Classroom Inside Out

By Indira Dutt

s a child at school I remember sitting in a stuffy portable looking out the window to the field and houses beyond. I felt constrained: my seat was attached to the desk, the classroom was just barely big enough to fit all of us, the windows were small, and the air was stale. I also remember the playground outside. I played hide and seek in the small stand of trees beside the field; I helped friends pile up the leaves in the fall and we all jumped in; I imagined an extraordinary museum of found objects–we made displays of the natural oddities that intrigued us and told stories about each treasure.

s a child at school I remember sitting in a stuffy portable looking out the window to the field and houses beyond. I felt constrained: my seat was attached to the desk, the classroom was just barely big enough to fit all of us, the windows were small, and the air was stale. I also remember the playground outside. I played hide and seek in the small stand of trees beside the field; I helped friends pile up the leaves in the fall and we all jumped in; I imagined an extraordinary museum of found objects–we made displays of the natural oddities that intrigued us and told stories about each treasure.

The two sides of the portable wall felt inexorably different and though I did well in school I was often wrangy in the classroom, wanting a little more of the freedom I felt when I was outside. Funny then that I should chose a career that keeps bringing me back into classrooms.

As a teacher I notice that, when the outside and inside feel completely separate, there is a problem. My teaching needs to be both connected and applicable to the everyday lives of my students and they need to feel free enough to be creative and capacious in their thinking so they can meaningfully participate in their education.

The literal and metaphorical notions of the outdoors are vital for me and so I work to soften the edge between inside and out.

One way I can do this is by creating and embellishing meaningful indoor–outdoor relationships. Connections between indoor spaces and outdoor areas are important “so that the outdoors becomes a natural extension of indoor learning” (Nair, Fielding & Lackney, 2009, p.111). This area of school design is sometimes overlooked or minimized by architects and educators, and this negatively influences students’ relationships to the natural world (Taylor, Aldrich & Vlastos, 1988).

Indoor–outdoor interfaces facilitate indoor–outdoor relationships. These interfaces are points, areas or surfaces that serve as a juncture between the inside and outside of a building. They include features that provide connection to the outdoors such as windows, skylights, natural building materials, aquariums, plants, interior living walls and porches. Even multimedia devices connected to the outside world via the Internet can bridge the gap between interior and exterior.

In 2009 I conducted a qualitative study that explored how intermediate students’ experience of the natural world was mediated by the design of their school building. My study site was the Bowen Island Community School (BICS) located on Bowen Island, a 20-minute commute by ferry from West Vancouver. The school was built on public land, parceled out of west coast rainforest. There are numerous large cedars and Douglas firs surrounding the property. I worked with grade six and seven students at BICS and collected data from two focus groups, semi-structured interviews, photographs and field notes.

One of the major findings of this study was that a school occupant’s experience of being inside their school building extends beyond the physical boundaries of the structure. When I asked students about their experience inside the school, they repeatedly spoke about the school grounds.

From a child’s perspective the whole school site as well as the school’s immediate A school occupant’s experience ofbeing inside their school building extends beyond the physical boundaries of the structure surroundings is a substantive part of their school experience. As well as being drawn to the outside, students expressed the significance of their sense of freedom, joy and beauty. Despite a focus on the fixed structure of the school building and school grounds, the student interviews were saturated with instances in which students reflected that indoor–outdoor connections deepened their freedom of movement, solitude, expression and imagination as well as the freedom to take mini-breaks from work. At BICS these instances of freedom were always associated with their connection to the exterior of the building. Students also recounted joy and places of beauty as critical in their learning.

I believe that my experience as a child varies little from students today. It is no surprise to any of us who have spent time in the classroom with children (of any age) that students’ attention is often drawn away from the topic or task at hand. I think that as teachers we get caught up in expending energy on refocusing, directingand corralling our students into the confines of the classroom, when instead we could find ways to capitalize on students’ desire to move outside. At times this movement is literal, but students’ imaginations can and do take them out in a figurative sense as well.

At BICS, teachers work with the imaginative drive and thirst for freedom that children have. The teachers at BICS incorporate the indoor–outdoor interfaces into the teaching process; they use the view from their classroom windows to highlight relevant elements of curriculum and they bring the children out into the hallway to stand or sit under the skylight and talk about the clouds outside. There is an active engagement with the outdoors from within the structure of the school.

While BICS is situated in what some might consider an idyllic teaching environment, certain aspects of the BICS students’ experience can be generalized to any location, rural or urban. If we can acknowledge the importance of freedom in the life of our students we can start to embrace and incorporate the interfaces to which we have access instead of thinking of classroom windows as distractions and covering them up using blinds or construction paper.

As a part of my research, I asked 55 grade six and seven students to draw an ideal school building, one that they thought would foster their connection with the natural world. I asked them to label important features they included. The most dominant features of these drawings were plants and animals. During my study I found that students expressed great joy witnessing the complete life cycle of plants. At BICS students could see the garden from their large classroom window. One student exclaimed, “It’s fun to watch everything [in the garden] because you go in the beginning of the year and there are little sprouts and then you go later and there are big shoots and stuff.” At a more urban school in Toronto each class grows a different kind of seed (grade one grows peppers while grade two grows tomatoes) and later in the spring they transplant their seedlings into the garden. In both these examples students develop relationships with food they eat in addition to having an indoor–outdoor connection.

As a part of my research, I asked 55 grade six and seven students to draw an ideal school building, one that they thought would foster their connection with the natural world. I asked them to label important features they included. The most dominant features of these drawings were plants and animals. During my study I found that students expressed great joy witnessing the complete life cycle of plants. At BICS students could see the garden from their large classroom window. One student exclaimed, “It’s fun to watch everything [in the garden] because you go in the beginning of the year and there are little sprouts and then you go later and there are big shoots and stuff.” At a more urban school in Toronto each class grows a different kind of seed (grade one grows peppers while grade two grows tomatoes) and later in the spring they transplant their seedlings into the garden. In both these examples students develop relationships with food they eat in addition to having an indoor–outdoor connection.

When resources permit, adding indoor–outdoor interfaces by creating a “living things zone” (Nair, Fielding & Lackney, 2009) can delight students and inspire observation and investigation. I noticed students would consistently gather around a seaquarium in the foyer at BICS and watch the sea creatures inside. One student exclaimed with joy, “You don’t see a seaquarium everyday. It’s my favourite. Sea cucumbers, yeah, they spit out their guts for protection.” Students used their excitement about sea creatures and ability to watch them for long periods of time to write daily observations and creative stories in their journals.

Living things zones can include elements such as plants, sprouts, a window farm, living walls, an aquarium and small animals. In some Waldorf classes, one daily routine (first and last thing of day) consists of each child retrieving their potted plant from a table top, bringing it to their desk for the day and then putting their plant back on the tabletop at the end of the day, watering it when need be. Each child sees their plant change over time, while having something small for which they are responsible, and they always have a living thing close at hand. Even this very small and relatively easy version of a living thing zone has a profound effect on students.

If we take a broader view of nature, and humans’ place within it, we might even conceive that the very busy urban street below a school window has natural lessons waiting to be learned. Rich conversations result when we explore what is happening beyond the walls of the classroom regardless of where our school is situated.

With our students’ best interests in mind we can utilize existing indoor–outdoor interfaces to enhance curriculum. While I feel a particular affinity for green spaces and places where dirt and water and clean air are easily accessed, in reality many schools occupy sites with precious little green or naturalized space. We can find ways to incorporate the nature outside, be it the trees or the bustle of humanity on city streets, in our classrooms to create an expanded sense of freedom and joy in our students.

References

Nair, P., Fielding, R. & Lackney, J. (2009). The language of school design: Design patterns for 21st century schools. Rev. ed. Minneapolis, MI: DesignShare.

Taylor, A., Aldrich, R.A. & Vlastos, G. (1988). Architecture can teach … and the lessons are rather fundamental. In Context, 18(Winter), 31–38.

Wilson, E.O. (1993). Biophilia and the conservation ethic. In S.R. Kellert and E.O. Wilson (Eds.), The biophilia hypothesis (31–41). Washington, DC: Island Press.

Indira Dutt is a graduate of the Center for Cross-Faculty (Architecture and Education) Inquiry in Education at University of British Columbia. She is currently participating in a Participatory Design Process at Cassandra Public School and working at Outward Bound, Evergreen Brickworks. This article was originally published in Pathways: The Ontario Journal of Outdoor Education 2010 23(2).

s an outdoor educator, I often get sucked into the false binary that lessons are either fun or informative, that content must be sweetened with games, stories, and activities like applesauce for children’s medicine. But stories are one of the oldest forms of teaching known to humankind, and games and interactive activities help students interpret and internalize what they learn on trails, in classrooms, and at home. In this article, I invite you to stop apologizing for your content teaching and start weaving it into lesson sequences that include stories, games, writing activities, and more. Sequences can make your teaching practices more effective, more equitable, and yes, more fun.

s an outdoor educator, I often get sucked into the false binary that lessons are either fun or informative, that content must be sweetened with games, stories, and activities like applesauce for children’s medicine. But stories are one of the oldest forms of teaching known to humankind, and games and interactive activities help students interpret and internalize what they learn on trails, in classrooms, and at home. In this article, I invite you to stop apologizing for your content teaching and start weaving it into lesson sequences that include stories, games, writing activities, and more. Sequences can make your teaching practices more effective, more equitable, and yes, more fun.

or the past two decades, books and articles written by place- and community-based advocates have been largely focused on defining and justifying an alternative approach to teaching and learning grounded in local knowledge and issues with the aim of inducting children into a sense of community participation and responsibility. This literature was largely exhortatory rather than prescriptive. It did not often provide interested teachers with detailed guidelines about how to move from a broad vision to the challenge of creating and enacting curriculum and instruction not limited by either textbooks or even classrooms. These advocates asked teachers to be courageous and take risks, trusting in their capacity to experiment and learn from their failures and successes. And many teachers across the United States and elsewhere became early adopters of this approach, willing to embrace those challenges and risks. As place- and community-based education enters its third decade, however, something more is needed to make its implementation appealing and understandable to a broader group of educators. Sarah Anderson’s Bringing School to Life: Place-Based Education across the Curriculum (2017) provides exactly the kind of guidance required to accomplish this end.

or the past two decades, books and articles written by place- and community-based advocates have been largely focused on defining and justifying an alternative approach to teaching and learning grounded in local knowledge and issues with the aim of inducting children into a sense of community participation and responsibility. This literature was largely exhortatory rather than prescriptive. It did not often provide interested teachers with detailed guidelines about how to move from a broad vision to the challenge of creating and enacting curriculum and instruction not limited by either textbooks or even classrooms. These advocates asked teachers to be courageous and take risks, trusting in their capacity to experiment and learn from their failures and successes. And many teachers across the United States and elsewhere became early adopters of this approach, willing to embrace those challenges and risks. As place- and community-based education enters its third decade, however, something more is needed to make its implementation appealing and understandable to a broader group of educators. Sarah Anderson’s Bringing School to Life: Place-Based Education across the Curriculum (2017) provides exactly the kind of guidance required to accomplish this end. Gregory Smith is a professor emeritus of the Graduate School of Education and Counseling at Lewis & Clark College in Portland, Oregon. He has written numerous articles and books about environmental and place- and community-based education. He is a fellow of the National Education Policy Center at UC-Boulder, a member of the education advisory committee of the Teton Science Schools, and a board member of the Cottonwood School of Civics and Science.

Gregory Smith is a professor emeritus of the Graduate School of Education and Counseling at Lewis & Clark College in Portland, Oregon. He has written numerous articles and books about environmental and place- and community-based education. He is a fellow of the National Education Policy Center at UC-Boulder, a member of the education advisory committee of the Teton Science Schools, and a board member of the Cottonwood School of Civics and Science.