by editor | Sep 15, 2025 | Conservation & Sustainability, Data Collection, Experiential Learning, Inquiry, Integrating EE in the Curriculum, Schoolyard Classroom, Student research, Teaching Science

Scotch Broom Saga:

Restoring a School Habitat as Project-Based Learning and Inquiry

by Edward Nichols and Christina Geierman

Since the advent of No Child Left Behind, many schools have turned their focus inward. Students rarely leave the classroom. Teachers often deliver purchased curricula that attempt to make meaningful connections for students. Lessons may contain examples from the real world, but these exist only on paper and are not explored within a real-world context. This article describes how an elementary school (K-5) on the southern Oregon coast addressed a real-world problem– the presence of the invasive Scotch broom (Cytisus scoparius) plant on the school campus. It began as a plan to improve an outdated writing work sample but became a school-wide project that allowed ample opportunities for students to authentically practice research skills while developing a sense of value for the world around them.

North Bay Elementary School is located in the temperate rainforest of rural Oregon, just a few miles from the Pacific Ocean. It serves about 430 students, over 95% of whom qualify for free and reduced lunch. The property was purchased many decades ago when the lumber mills were booming and so was the population. It was built as a second middle school, and the grounds had plenty of room to build a second high school. But the anticipated boom never came, and the property eventually became an elementary school surrounded by a small field and a 50-acre forest. At some time in the past, an enterprising teacher had cut trails through the forest for student access. When that teacher retired, the trails largely fell into disuse.

The Seed of an Idea

In Oregon third-grade students must perform a writing work sample each year. The topic in North Bend, which had been handed down from previous teachers, was invasive species. The class would work together to write a paper on an invasive species found in Florida, then apply their writing process knowledge to produce a sample on an Oregon invasive. They were given three curated sources created by using a lexile adjuster on the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife website. This project existed in a relative vacuum– invasive species were not mentioned before or after the work sample. Its only connection to the rest of the curriculum was the writing style. The students were interested in the topic and produced decent work, but Edward Nichols thought they could do better. He had long noticed multiple patches of Scotch broom growing just off the school playground. This invasive plant out-competes native ones and does not provide food or useful habitat for other native species. He wondered if they could do something with this to enhance the writing work sample and turn it from a stand-alone project to something more meaningful.

Fertile Ground

That summer, Edward attended a Diack Training held at Silver Falls State Park. In addition to providing excellent professional development on how to perform field-based inquiry with your students, it is also a place where you get to meet other educators with similar mindsets.

A chance conversation with Julia Johanos, who was then serving as Siuslaw National Forest’s Community Engagement and Education Coordinator, led to the idea of having an assembly on invasive plants for all students at North Bay Elementary. Edward was also a member of the Rural STEAM Leadership Network, and he met Jim Grano in their monthly Zoom sessions. Jim is a retired English teacher who is now focused on getting students outside. He has helped several schools in the Mapleton area start Stream Teams, which got students outside restoring stream habitat and collecting data on salmon. He routinely led student groups into the field to remove English ivy and Scotch broom. Edward invited him to help lead a similar event at North Bay.

The Big Event

The Big Event

After weeks of planning, North Bay held a service learning day on March 17, 2023. The kickoff happened the day before when Julia Johanos led an engaging school-wide assembly on why invasive species are bad for our environment. The next day, the entire school participated in removing Scotch broom from the forest. The students came out one grade band at a time in 45-minute shifts. Each grade had a different task. Kindergarten students pulled the seedling Scotch broom by hand. Slightly larger stalks required “buddy pulls”, where two students worked together. Fourth and Fifth grades used weed wrenches to remove bigger plants. Alice Yeats from the South Slough NERR briefed each group on safety. And dozens of parent volunteers kept everybody safe. The Coos Watershed Association donated native plants, and the second grade came out at the end of the day to plant coyote bushes and red flowering currant, native strawberries, Oregon grape, and a variety of evergreen trees in the spaces the broom used to occupy. After school, Christina Geierman, a science teacher at North Bend High School, brought high school volunteers from the Science National Honor Society to help pull the biggest broom of all and clean up after the event.

Sustaining the Excitement

It is a tradition at North Bay to have a variety of fun activities for the last day of school. This year, in addition to the stalwarts of bubble soap, bicycles, and bounce houses, the event also contained a Scotch broom pull led by Jim Grano. Students could do whatever activity they chose, and many students chose to remove the broom from the edge of the playground. A representative from OSU Extension was also there, showing the kids how to make bird feeders, and folks from the South Slough NERR returned to lead nature hikes. The Confederated Tribes of Coos, Lower Umpqua, and Siuslaw Indians (CTCLUSI) also ran a booth and taught students about conservation and had them play a native game called nauhina’nowas (shinny), which involved using tall, carved sticks to pass and catch two balls connected by twine.

A second, school-wide Scotch broom pull occurred this past fall. Edward also started a Forestry Club at North Bay, which featured guest speakers from the Bureau of Land Management and had the students planting more native species. Plans are underway to have a school-wide pull each spring and a forestry club each fall to plant native species just before the rainy season hits.

Applying Their Knowledge

Applying Their Knowledge

Students participating in the Scotch broom pull apply their classroom knowledge in various ways. In mathematics, they record and tally the number of plants removed, practicing authentic math skills. They observe and document the plant’s lifecycle during the pull, connecting classroom biology lessons to real-world applications. North Bay uses the Character Strong curriculum to address social-emotional learning, and the broom pull allows students to apply traits like perseverance, cooperation, and service. Students can immediately and directly see the results of their efforts when they go outside for recess. This gives them a sense of pride in their accomplishments. There have been many reports of students educating their parents about why Scotch broom should be removed from the environment and even a few tales of students removing invasive plants from their own properties.

While participating in the Scotch broom pull, the students met a variety of scientists and conservationists. They were able to make a connection between this sort of work and future job opportunities. Jim Grano showed them that, if you feel passionately about something, you can make a difference as a volunteer. Alice Yeats, Julia Johanos, and Alexa Carleton from the Coos Watershed Association showed them that women can be scientists and do messy work in the field just as well as men can. Although it will take many years to tell, we hope that a few students will be inspired by this work to pursue careers in natural resources management.

Into the Future

This past fall, North Bay was named a NOAA Ocean Guardian School. This means that NOAA will provide the funds necessary to carry this project forward and expand it. The grant is renewable for up to five years. This spring, a group of students from North Bay will host a booth at Coos Watershed’s annual Mayfly Festival. There, students will present their project to members of the public and urge them to remove Scotch broom and other invasives from their own properties.

This spring, the North Bend High School Science National Honor Society (SNHS) will partner with North Bay students for a Science Buddies Club that will take place after school. Thanks to a Diack Grant awarded to Christina Geierman and Jennifer Hampel, the SNHS has a variety of Vernier probes and other devices that can be used to collect data in the forest. In the first meeting, the North Bay students will guide the high schoolers down the forest trails and describe their Scotch broom project. The SNHS members will show them how the probes work and what data we can gather. The guiding question will be, “Why do Scotch broom live in some areas of the forest, but not others?” The students will come up with hypotheses, focusing on one variable like temperature, light availability, etc. and then work together to gather and analyze the data. Students will present their data in a poster at the Mayfly Festival and possibly the State of the Coast Conference.

Members of the North Bend High School Science National Honor Society and family volunteers have reopened the trails through the forest. Plans are underway to expand these trails and partner with the CTCLUSI to create signage. The forest is being used by the school once again. Classrooms that earn enough positive behavior points can choose nature walks through the forest as potential rewards. Dysregulated students are taken down the path to calm them. Increasing student and community use of the forest is one of our future goals.

Edward Merrill Nichols is a 3rd-grade Teacher at North Bay Elementary in North Bend, Oregon. Growing up on the southern coast of Oregon instilled in him a love of and respect for his natural surroundings. With over six years of experience, he fosters student growth through engagement and respect. Edward actively engages in STEM education, leading Professional Development sessions and extracurricular clubs. He holds a Bachelor of Science in Education and a Master of Science in K-8 STEM Education from Western Oregon University.

Edward Merrill Nichols is a 3rd-grade Teacher at North Bay Elementary in North Bend, Oregon. Growing up on the southern coast of Oregon instilled in him a love of and respect for his natural surroundings. With over six years of experience, he fosters student growth through engagement and respect. Edward actively engages in STEM education, leading Professional Development sessions and extracurricular clubs. He holds a Bachelor of Science in Education and a Master of Science in K-8 STEM Education from Western Oregon University.

Christina Geierman has taught physics, biology, and dual-credit biology at North Bend High School for eleven years. She is a published scientist, a proud union member, a decent trombone player, and a world traveler. She enjoys spending time outside with her husband, Edward Nichols, and dog, Aine.

Christina Geierman has taught physics, biology, and dual-credit biology at North Bend High School for eleven years. She is a published scientist, a proud union member, a decent trombone player, and a world traveler. She enjoys spending time outside with her husband, Edward Nichols, and dog, Aine.

by editor | Sep 8, 2025 | Gardening, Farming, Food, & Permaculture, Schoolyard Classroom

In Pursuit of Environmental Literacy:

Abernethy Elementary’s

Farm-to-School and School Garden Program

by Sarah Sullivan

At Abernethy Elementary, students enjoy freshly cooked breakfasts and lunches prepared on site by a trained chef. The meals are often prepared with local and seasonal ingredients harvested from the school’s Garden of Wonders. The garden itself is entirely planted, tended and harvested by the students, who use it throughout their school day as a “learning laboratory. “

The garden program and scratch kitchen are parts of a unique wellness policy at Abernethy. A full-time physical education teacher encourages the students to enjoy physical activity. Enthusiastic parents walk and bike their kids to school rather then driving. Parents and staff organize a yearly bike-a-thon to raise money for the school that allows Abernethy students to ride bikes and scooters on car-free streets. Chef Nicole and Garden Coordinator Sarah Sullivan run five weeks of summer camps at the school, where they teach everything from pickling to pasta making, permaculture and organic bio-intensive gardening.

Founded in 2000 by a dedicated group of parents and teachers, the School Kitchen Garden program began as just a community garden plot. Teachers agreed to add garden class as an additional extracurricular class for students. In the past 11 years, the program has grown to include a rigorous garden curriculum aimed at supporting state standards in math, science, English, health and social studies. (Look for a free compendium of these teacher-friendly garden lessons for grades K-5 online this spring!)

Sample Curriculum: Integrating Benchmark Standards into the Garden

As part of the children’s graduation from the Garden of Wonders Program, 4th graders get to design and plant the garden and reap what they sow over the summer and into the fall of their 5th grade (final) year at Abernethy Elementary. During the winter small groups of students spend several weeks planning out a small garden plot collaborative, determining what crops grow when, how far apart they like to be spaces, how to maximize yield, make the garden beautiful, and design the garden with diversity in mind. Then they get to carefully measure, plot, and map their garden bed using math, language, and  conceptual skills carefully aligned with the lessons that they are learning in their homeroom class. Soon string is laid out to carefully map out the garden beds into 1 x 1 foot plots and the children start planting greens and cool-loving plants in the garden classroom as early as January, examining the little seeds, carefully reading seed packets, then planting them in little pots in the window.

conceptual skills carefully aligned with the lessons that they are learning in their homeroom class. Soon string is laid out to carefully map out the garden beds into 1 x 1 foot plots and the children start planting greens and cool-loving plants in the garden classroom as early as January, examining the little seeds, carefully reading seed packets, then planting them in little pots in the window.

Students also take soil samples and determine how their soil quality is by analyzing how much silt, sand, loam, and clay is in their assigned garden bed. In March they turn all of the winter cover crops into the soil, add compost, and carefully dig and rake the garden to get it all ready for seeding and transplanting.

Time and time again we see that some of the students that struggle in the classroom excel in the garden. As kinesthetic and visual learners, those students often become leaders in the outdoor classroom. The most gratifying part of our work is to see the “aha” moments in the garden: suddenly the spark for a love of learning is lit and here, in the garden, students may reap what they sow.

The garden curriculum at Abernethy gives students the opportunity to learn about native plants, the origin of the foods that we eat, the interconnected relationships of micro-organisms in soil, the importance of food security, the art of cooking and much more. Students leave Abernethy with a deep sense of the interconnectedness of human and planetary healthy, and a full understanding of where their food comes from.

Portland Public School’s Test Kitchen for Higher Quality Food:

Abernethy serves as the “test kitchen” for Portland Public Schools and has created many recipes and menu items that have moved into schools across the district. Interestingly, though average percentage of students buying hot lunch daily at Portland schools is about 30 percent, over time lunches from the Abernethy kitchen attract at least 60 percent of the school’s children.

School Chef Nicole Hoffman is working closely with Nutrition Services (NS) to create interesting recipes that still meet USDA standards with only $1.07 per meal to work with. Together Hoffmann and NS have focused on sourcing better staple ingredients to institutionalize wide-sweeping change: All wheat used is Portland Public Schools, for example, is grown sustainable and locally by Shepherds Grain flour. All chicken is raised locally and hormone-free by Draper Valley farm. Beans and grains are grown by farmers in the Willamette Valley. Yogurt is made in Eugene, Oregon. At this point Portland Public Schools are serving about 40% locally-sourced food.

Slowly but surely Abernethy’s students are even fans of the more “creative” dishes from the kitchen like chef Nicole’s chicken Panang curry, falafel with riata, hummus and pita, and garden-harvest veggie soup.

Community Involvement:

Abernethy has become an hub for community outreach and education: students and neighbors unite to study why growing organic food is so important, how to best utilize urban-green space and successfully grow edible natives, low-maintenance landscapes and vegetables in our unique climate and soil. We see bridging the gap between the school and neighboring community in collaborative projects and stewardship as absolutely essential for city-wide sustainability.

For example, forth graders decided to reach out into the community in hopes of finding nearby garden space to grow more food in a public area as a demonstration plot for local food security and organic gardening. The local hardware store responded, offering four raised garden beds on busy Hawthorne Boulevard for students to steward. Forth graders planned the plots entirely, planting a diversity of crops important in different cultures like Thai basil and Mexican chili peppers.

Students took pride in their garden plots, and gained a sense of stewardship in knowing they were bettering our neighborhood and sharing their skills and the bounty with others. Much of the produce grown by the children was donated to the local Loaves and Fishes, supplementing food served to housebound elders.

Research shows that school gardens:

- -Improve social skills and behavior.

DeMarco, L., P. D. Relf, and A. McDaniel. 1999. Integrating gardening into the elementary school curriculum. HortTechnology 9(2):276-281.

- -Improve environmental attitudes, especially in younger students.

Skelly, S. M., and J. M. Zajicek. 1998. The effect of an interdisciplinary garden program on the environmental attitudes of elementary school students. HortTechnology 8(4):579- 583.

- -Instill appreciation and respect for nature that lasts into adulthood.

Lohr, V.I. and C.H. Pearson-Mims. 2005. Children’s active and passive interactions with plants influence their attitudes and actions toward trees and gardening as adults. HortTechnology. 15(3): 472-476.

- -Improve life skills, including working with groups and self-understanding.

Robinson, C.W., and J. M. Zajicek. 2005. Growing minds: the effects of a one-year school garden program on six constructs of life skills of elementary school children. HortTechnology 15(3):453-457.

- -Increase interest in eating fruits and vegetables and improve attitude toward fruits and vegetables.

Pothukuchi, K. 2004. Hortaliza: A Youth “Nutrition Garden” in Southwest Detroit. Children, Youth and Environments 14(2):124-155.

- -Have a positive impact on student achievement and behavior.

Blair, D. (2009). The child in the garden: an evaluative review of the benefits of school gardening. Journal of Environmental Education 40(2), 15-38.

The increase in students’ openness to trying new things, their passion for gardening and getting outdoors, the positive feedback we get from parents and teachers all speak to the great success of this program.

Accolades from Across the Nation:

Oregon Green School status

First Oregon Wellness Award

Kiwi Magazine Crusaders Award

Health Magazine 2008 Healthiest Schools Report

Subject of 2007 NPR story on school food (LINK TO http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=6515242)

KPTV feature “Food Revolution” Link to http://www.better.tv/videos/m/30671714/food-revolution.htm

Oregon Live

Check out Chef Nicole and Abernethy’s School Kitchen Garden Program on Facebook or on the website: www.gardenofwonders.org

More information: gardenofwonders@yahoo.com

Written by Sarah Sullivan, Abernethy School Kitchen Garden Program Coordinator

Edible Corvallis

by Sara McCune

As the Farm to School movement breezes across the country, the community of Corvallis, Oregon has wasted little time in becoming involved. This school year marks the fourth year that the Corvallis Environmental Center has been implementing Farm to School related programming in the Corvallis School District through its Edible Corvallis Initiative. What began as monthly taste tests of seasonally available produce at one school has grown into a full-blown farm to school program: Tasting Tables at all 11 elementary and middles schools in Corvallis, science curriculum-based farm field trips, classroom cooking lessons, and an ever increasing amount of local food purchased by the school district itself. The Corvallis Farm to School program is primarily funded by an Oregon Department of Agriculture Specialty Crop Block Grant with additional support from Slow Food Corvallis, the Consumer Wellness Center, Pacific Source Health Plans, and individual donors.

The Tasting Table program allows upwards of 4,000 elementary and middle school students to have a connection with the Farm to School program. Each month, the students have a chance to taste a local “Harvest of the Month” while learning about the farm where the produce was grown and the nutritional benefits of that fruit or vegetable. Increased exposure to local, seasonal produce will give a boost to local farms while expanding the palates of Corvallis youth.

In addition to Tasting Tables, the Edible Corvallis Initiative hosts first, second, and third grade classes at its Starker Arts Garden for Education for one-hour field trips. These field trips are designed to complement and enhance the science curriculum kits that are already used in Corvallis classrooms. Rain or shine, the kids and teachers love their time in the garden, nibbling on dewy bits of kale, planting garlic, or digging in the compost for bugs.

Because learning how to eat well involves food preparation, Corvallis’ Farm to School program offers in-classroom cooking lessons as well as after school cooking clubs at several of the elementary schools. Through the course of these lessons, the students become empowered to make healthy food choices by learning to cook delicious meals and snacks with locally grown produce. Children leave the classroom excited about green garden dip or butternut squash soup, dishes their parents may never have dared to serve.

A particularly exciting component of the Corvallis Farm to School program is its direct connection to the Corvallis School District’s department of Nutrition and Food Services. For several years, Food Services has worked with the Edible Corvallis Initiative to facilitate Tasting Tables and the promotion of locally grown produce. Beginning this year Sara McCune, the Edible Corvallis Initiative’s Farm to School Coordinator now spends half of her time working directly with Sharon Gibson, the director of Food and Nutrition Services. Together Sara and Sharon work to significantly increase the amount of local food purchased by the school district beyond the days that Tasting Tables are held and to turn the cafeteria into a healthy place where students can expect to learn about the food they are eating and the process it underwent before it arrived on their cafeteria trays.

Sara McCune is Farm to School Coordinator for the Edible Corvallis Initiative, Corvallis Environmental Center

CREST Farm to School

by Bob Carlson

CREST is an environmental education center operated by the West Linn-Wilsonville School District. One of the key CREST programs is the CREST Farm. The farm is located on surplus district property. Currently, a half-acre of land is producing vegetables for school cafeterias and other uses. Last summer, middle school and high school interns learned how to grow, maintain, and sell vegetables from a farm stand on site. Next summer, the students will operate a 20 family CSA in addition to running the farm stand.

The farm is also used as a field trip destination for K-12 students year round. Each season approximately 600 students visit the farm. Learning activities are tailored to the needs of individual teachers or teams of teachers. Many of the trips emphasize wellness and the benefits of eating fresh healthy fruits and vegetables. Other field trips focus on sustainable agricultural practices that help conserve resources and promote a healthy ecosystem. Lessons include biodynamic farming practices such as maintenance of soil health, natural pest management, crop rotation and wise use of water. Students participate in hands on activities including: planting, thinning, pruning, composting, amending soil, and harvesting.

All of the farm lessons promote ecological literacy by helping kids understand their connection to food and how the production of food can affect ecosystems. They gain an understanding of the delicate balance of ecosystems and the interconnected web of living things.

One of the goals of the farm is to give students a chance to make a difference in their community and the world by participating in service learning. Some students participate in projects that provide food to local food banks and support sustainable agriculture projects in other communities and other countries.

A number of CREST staff help run the farm and create meaningful educational experiences for students. A professional farmer lives on-site and provides technical expertise, a part-time grant-funded educator runs field trips and the internship program, and an AmeriCorps member recruits community volunteers and establishes systems for distributing the food to school cafeterias. She is also offering tasting programs to schools to promote increased consumption of vegetables and fruits.

Bob Carlson is the CREST Director.

by editor | Sep 1, 2025 | At-risk Youth, Critical Thinking, Experiential Learning, K-12 Activities, Schoolyard Classroom

by Abigail Harding and Corwyn Ellison

“We do not learn from experience, we learn from reflecting on experience.”

-—John Dewey

When we walk silently in the forest we allow ourselves to deepen our connection and strengthen our appreciation for the natural world. Suddenly, we hear animals unfamiliar to us, and observe natural phenomena we never stopped to notice. Exposure to the natural world and reflection is beneficial to physical and mental well-being. The psychological power of a reflective solo walk is astounding—so much so that conscious reflective thought has been shown to change the very structure of our brains.1 Experience-based learning is more powerful when coupled with reflection. Reflection is defined as an intentional effort to observe, synthesize, abstract and articulate the key learnings gathered from an experience.2 When implemented intentionally, solo walks provide a context in which both experiential education and mindfulness converge for the benefit of student learning.

A solo walk is a relatively simple concept: an individual walks alone on a trail or perhaps through the neighborhood to connect, reflect or reason through an event, emotions, or anything else that comes up during that time. It is not novel, but can be revolutionary for the individual participating in it. Using solo walks to introduce observation and reflections skills to students is not only effective in learning, but also important in connecting with themselves, the community, and the environment. In this article we will provide a framework for conducting solo walks with students in natural settings.

What is a solo walk?

A solo walk is an independent, thought-provoking walk through a relatively isolated area. A key goal of a solo walk is to practice observational skills and promote critical thinking, and introspective thought in students. This is accomplished through both the solo walk itself, and reflective journaling and debriefing after. During the walk students are guided both in their direction on the trail and mindful awareness by cards spaced ten to twenty feet apart on the ground. The cards may include a topical quote, a prompt for journaling or action, a direction, or perhaps a question to ponder. These cards can be customized and adjusted to suit the needs of the students and to meet learning goals. Common categories for cards include introduction/closing, thought-provoking questions/quotes, observation/sensory prompts, directional signs, and anything in between. For example, a card may say, “Stop here until you hear two bird songs” or “Where was this boulder 100 years ago? 1,000 years ago?”

How do you do a solo walk?

A non-complex trail or route should be chosen ahead of time. To avoid confusion, a card indicating direction of travel should be placed at all junctions the students encounter during their walk. A typical trail length is approximately ¼ mile. Two instructors or adults are necessary for the solo walk. The process and implementation should be discussed ahead of time. Students begin by gathering at the head of the route. Instructor A will introduce the solo walk as a reflective activity and play a game with the students as they wait to begin their solo walk. Be clear to students about expectations, the benefits of doing a solo walk, and why it is important for them to walk slowly and silently throughout. Emphasize that if they see someone in front of them, they should slow down, perhaps spend more time at the current card, and give the person ahead time to walk out of sight.

After roll-out, Instructor B leaves to set out the cards on the trail. Approximately five to ten minutes later, instructor A begins sending one student at a time down the trail for the solo walk. Each student is sent down the trail in two-minute intervals. The order in which they are sent can be determined ahead of time by the instructors or the decision can be student-directed.

At the end of the solo walk, Instructor A will be waiting in an area in which students may silently sit and journal reflectively about their experience. This location should be large enough for the entire group and should be comfortable for students. After all students have returned and journaled, Instructor B will walk the trail, pick up the cards, and rejoin the group. At this point a debrief will occur. Since students will be arriving to the end location at different times, it is important to have an activity ready for them to complete while they wait. This could be journaling, drawing or using watercolors to illustrate something they noticed during the walk, sitting quietly and observing, or any other quiet independent activity.

The debrief

Debrief is one of the most important components of a solo walk, particularly when it is focused on reflecting, synthesizing, and sharing their experience. Responding to one to two pre-written questions in a journal while students wait for the rest of the group is a constructive activity that prepares them for sharing later. To accommodate different learning styles, offer students a choice of responding in a way that feels valuable to them i.e. writing, sketching, or a combination. Once all students have completed the walk and journaling, give them an opportunity to share in pairs and/or as a group. The act of sharing their experiences can be very powerful, but also recognize that not all students will want to share to a large group and, in those cases, sharing with one other person is sufficient.

Some examples of debrief questions can include:

What surprised you about this experience?

What was your favorite card? What cards would you include?

What advice would you give other students for their solo walk experience?

What are two things you learned and can use in daily life?

Use a mix of questioning strategies to draw out student reflection, and be clear about discussion norms to ensure emotional safety during a group debrief. Using the solo walk cards again for debrief is an effective way to provoke group discussion. Solo walk cards can be placed in a pile on the ground, students can then pick their favorite card and share with the group why this card was chosen. Similarly, cards with a variety of emotions written on them may be used to promote a deeper discussion about feelings.

Table 1. The solo walk implementation guide

Goal To practice reflection, critical thinking, introspective thought, and scientific observation skills.

Objective Students will be able to:

· Journal in a reflective manner

· Complete a solo walk in an isolated area

· Participate in group discussion in a meaningful way

Audience Age group: any age

Number of individuals: 10-15

Duration How long is the lesson? 60 minutes

How long will it take to follow up the field experience? 10-20 minutes for debrief

Location An appropriate trail route and length based on the group’s abilities and needs. Check location ahead of time to identify potential risks. Alternative options include: school hallways, or any green space that provides opportunity for solitude.

Management and safety Students are supervised at beginning and end of trail. Trail is appropriate in level of difficulty and complexity. Junctions are marked with clear directional signs. Emotional safety is addressed by partner walking or pairing a child with an adult.

Equipment · Prompt cards (25-50)

· Activity for before and after solo walk

· Writing utensils

· Student journals

The debrief activities are an excellent opportunity for both teachers and students to assess student experience, knowledge and insight resulting from a solo walk. This information can be used to guide future learning activities and goal setting.

Teaching applications

Solo walks as a tool

For teachers, a solo walk is a versatile tool that can be planned to meet a variety of learning objectives. How you frame the activity, when you conduct it, what cards you choose, the order in which they appear on the trail, and the debrief strategy are all opportunities to guide students towards a specific goal or outcome. For example, a solo walk can be used:

In the beginning of a week to introduce students to and help them connect with a new setting

To ground a group of individuals with mindful awareness and space for reflection

At the end of a week so students can reflect on all that they have accomplished and how they might transfer these skills to their daily lives

Before and/or after a team building activity

Solo Science

In science education settings, students are often bombarded with new techniques and terminology. Solo walks provide the solitude necessary for students to ponder, dissect, and make sense of complex concepts in a tangible way. Because solo walks are inherently independent, students can use scientific tools without any external influence, and think critically of the world around them without fear of failure. Instructors may choose an investigative topic to center the solo walk around or design a mini independent investigation to be conducted during the solo walk. For example, an investigative topic may be plant and animal adaptations. The pictures below are examples of how we have woven scientific practice into the solo walk experience.

Connecting to classroom and beyond

Solo walks offer an incredible opportunity for students to develop awareness and practice active reflection that is an essential and valuable tool in lifelong learning. It can be a transformative experience and its adaptability make it a valuable tool for teachers. Give your students ownership over their experience by having them create their own solo walk cards. Cards can be written in any language, made of recycled material, cut into shapes, etc. Get creative and make it work for you and your students!

Advice from the field

Here are some tips gathered from a survey of 39 outdoor educational professionals with experience facilitating solo walks:

• Keep objectives broad, learners will get different things from the experience. The learning goal can be as simple as having time alone in the woods and it will still be powerful.

• Utilize a variety of cards and consider how the cards you use will support a larger theme or create a desired experience or outcome. Use short, relatable quotes from a diverse group of people with different backgrounds and cultures.

• Check the trail ahead of time and bring a few extra cards and markers to take advantage of teachable moments. Let the trail speak to you. If it is windy, use rocks to weigh the cards down and if you are teaching in a place like the Pacific Northwest, make sure your cards will survive the rain.

For some students, walking alone in the woods can create anxiety or bring out behavioral challenges. Work with students on ways to help them feel safe and explain that it can be a challenge by choice. You can help by sharing your own experience with solo walks, pairing students together or with an adult, being intentional with the line order, giving directions silently, etc.

Have fun and get creative!

References

Kolb, David A. (2014). Experiential learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. Case Western Reserve University. Prentice Hall PTR, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey

Giada Di Stefano, Francesca Gino, Gary Pisano & Bradley Staats. March 2014. Learning by Thinking: How Reflection Improves Performance. Harvard Business School Working Knowledge. Retrieved from https://hbswk.hbs.edu/item/learning-by-thinking-how-reflection-improves-performance.

Wilson, Donna & Conyers, Marcus. (2013). Five Big Ideas for Effective Teaching: connecting mind, brain, and education research to classroom practice. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Zelazo, P. (2015). Executive function: Reflection, iterative reprocessing, complexity, and the developing brain. Developmental Review. Volume 38, 55-68.

Abigail M. Harding and Corwyn A. Ellison are environmental educators and graduate students at IslandWood and the University of Washington.

Abigail M. Harding and Corwyn A. Ellison are environmental educators and graduate students at IslandWood and the University of Washington.

by editor | Aug 26, 2025 | Outdoor education and Outdoor School, Place-based Education, Schoolyard Classroom

by Jane Tesner Kleiner

We know that for kids of all ages, play equals learning. And play comes in many forms, such as team sports, partner games and individual kids creating their own play. Play can also be active, passive or quiet. Learning also comes in many forms, such as visual, auditory, kinesthetic, and reading/writing. Kids love to explore, discover, question and dive into the world around them.

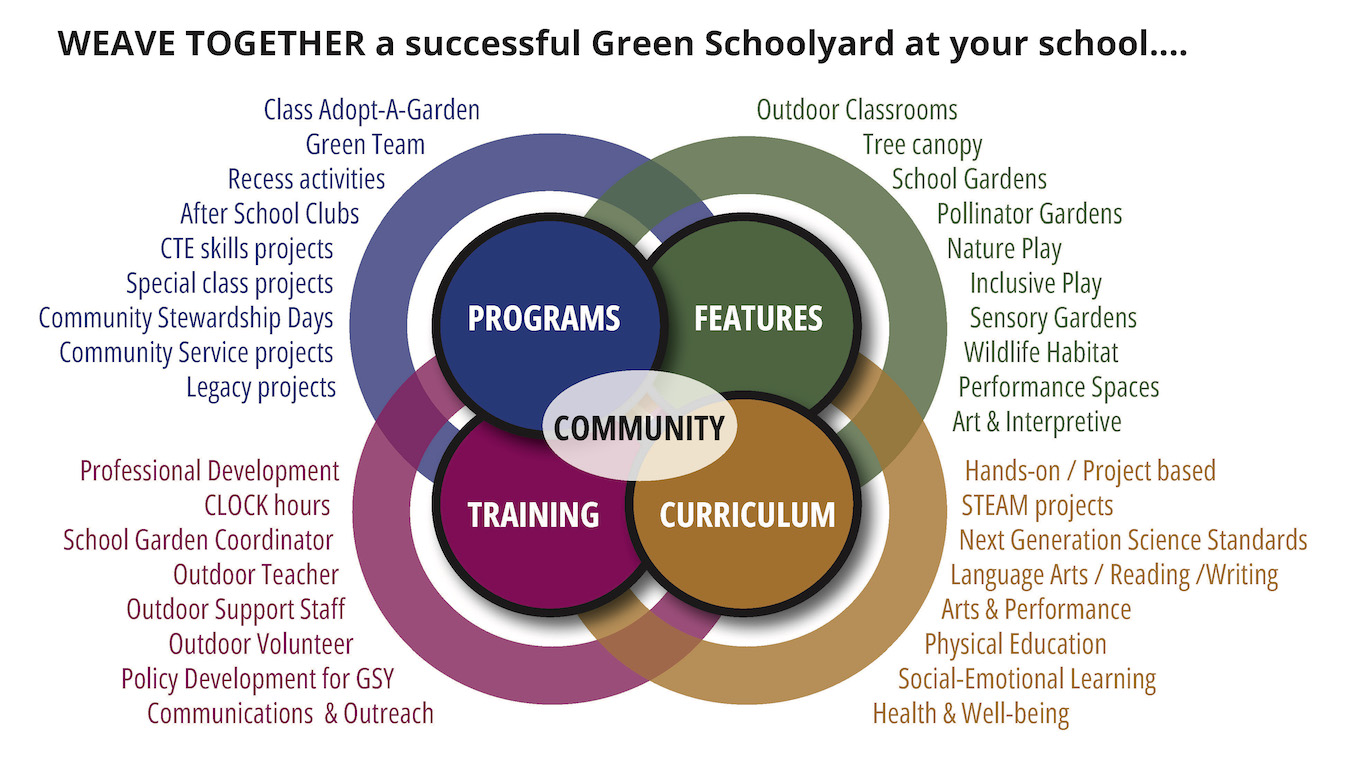

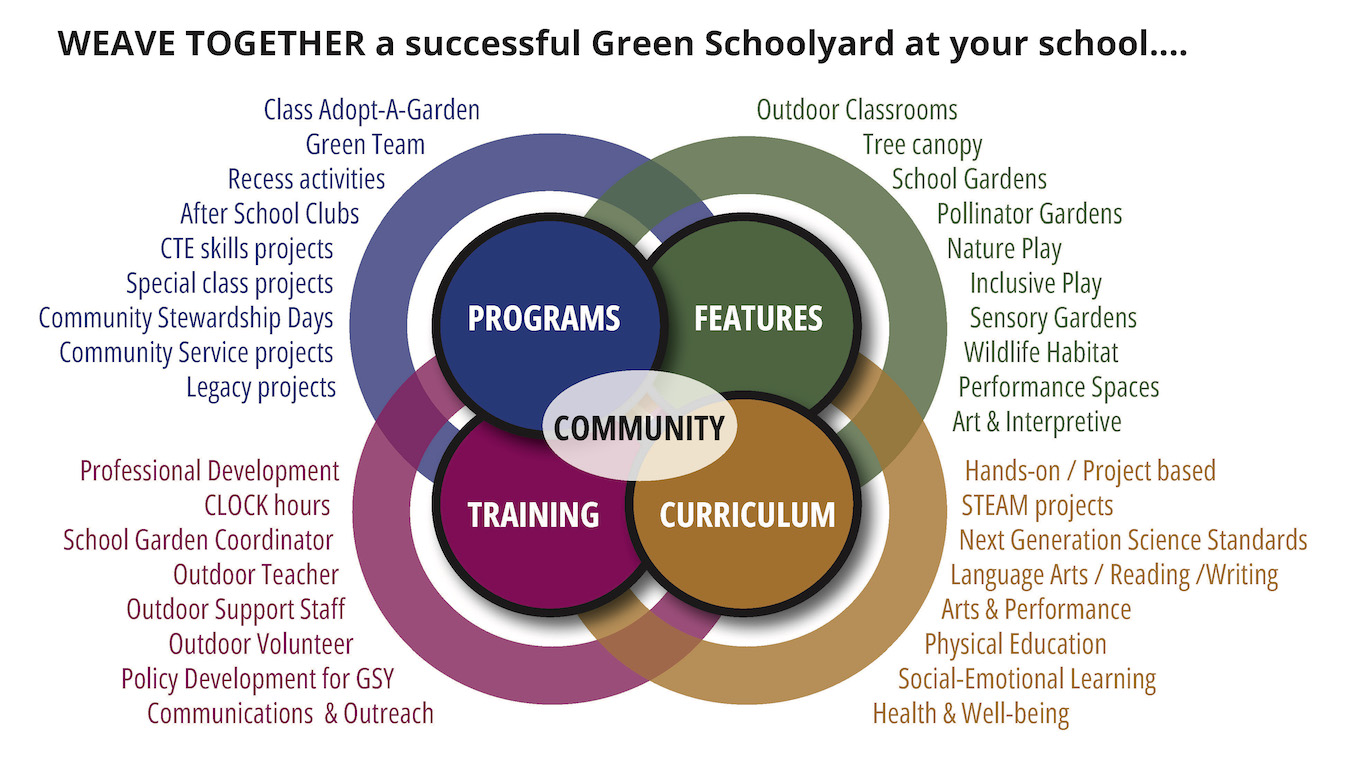

Many school campuses put the majority of focus on the building and what is happening inside and miss the opportunities to enhance the entire campus for learning, play and wellness.

What is there to gain by using the whole campus? A whole lot!

A Green Schoolyard looks at the entire property, from fence to fence, at the potential that could be across the whole property if money, time and energy were available. A majority of schools in our communities have landscape that is required by code, such as street or parking lot trees. But the majority of where people spend their time, is absent of nature and places to engage beyond active play and sports fields. When we consider adding nature and diverse features for all types of users and activities, we see a much greener campus.

As many of the articles, books and web pages in the Resource section will tell you, Green Schoolyards provide numerous benefits. There is also a role for every member of the school community to contribute to the on-going success of Green Schoolyard campuses. There can be a fine balance between meeting safety and security with diversifying features so that all can safely enjoy outdoors as well as feel welcome to enter and explore.

Here are just a few examples of benefits:

From the Children & Nature Network – Not only do Green Schoolyards promote learning through improved academic performance, increased attention span, and provide opportunities for diverse play, but also improving community cohesiveness, create activities for family engagement, improve health and wellness and enhance the environmental habitats.

Many research studies have indicated that:

- View of trees and natural settings outside of classroom windows can calm and reduce stress of students (and I can imagine staff, too)

- Diverse play features promote opportunities to increase social-emotional learning through working and playing with other students

- Working in gardens provides equitable access to nature for all students, regardless of age, academic capabilities or learning styles and provides mental health benefits

- Adding gardens and habitat features helps students feel ownership of their campus and can reflect the neighborhood needs for both in-school lessons and after school and breaks.

Other benefits that support implementing Green Schoolyard projects include:

- School districts tend to be significant land owners, providing opportunity to increase natural areas throughout urban and suburban communities.

- Projects can benefit mutual community goals, such as tree plantings and pollinator gardens to meet Climate Action Planning & Resiliency efforts, Urban Tree Canopy projects to reduce heat island effects, creating more public access to parks and green spaces with joint use agreements, etc.

- For middle and high schools, Career Education Technology (CTE) projects and programs can create on-site field stations and learning labs for horticulture, environmental science and natural resources. Green Schoolyards create equitable access for all students within walking distance of the building and provide an opportunity to have professional partners to support career-ready learning on-site.

- Stewardship and community service projects help nurture and care for the new spaces, features and plantings.

Accessible pathways provide equitable access to fitness on campuses, as well as walking loops for “walks and talks” or de-escalation walks.

- Green Schoolyards provide daily, weekly, monthly access to nature to familiarize students to nature, which is especially important for students who have little contact with nature. Learning about what to see, explore and understand at school will help build for successful trips away from campus, including Outdoor School trips are remote learning centers.

Campus improvements lend themselves to engaging community partnerships including donations of materials, expertise and activities.

The list of benefits vary, of course, by school, district and community. But each school has the opportunity to look at what their needs are for building success of students, staff and the community and finding projects that bring people and nature together.

by editor | Aug 26, 2025 | Gardening, Farming, Food, & Permaculture, Outdoor education and Outdoor School, Place-based Education, Schoolyard Classroom

Special Issue: Understanding Green Schoolyards

Picture a noisy elementary classroom, with bustling kids cleaning up from a morning of schoolwork. Then see the doors swing open and they head outside for some fresh air and play. Some students make a straight line right to their favorite equipment, like the swings. Some head for sports, like basketball or soccer. Still others may skip over to the play structure, start a game of tag or simply race around the equipment.

Does your vision stop there? Some, probably more than you think, need quiet space and decompression time, alone or with friends. Maybe they walk a loop path while chatting about a new pet, or maybe they give voice to their nervousness about an upcoming test. Given the chance, some would stroll over to a table under a tree, carrying a good book or some art supplies. If their school’s leadership is forward-thinking, some kids will head for a nature play area, where you may see them avoid the “lava” while traversing from log to boulder to log. Still others might roam the whole of the area, collecting leaves, twigs, flowers, and cones to craft something at the outdoor building tables.

If you have envisioned all of this, then in your mind’s eye you’ve built a Green Schoolyard. You might also hear terms such as Community Schoolyards and Living Schoolyards, as the concepts are similar – connect kids to nature in their neighborhoods.

“School” is about more than the indoor, classroom environment. A school’s entire campus creates an integrated experience for students, staff, and neighbors, both in terms of

activity and perception.

Green Schoolyards complement academic achievement. There is a significant body of research connecting children’s performance in school and the role that their environment plays. Views of nature, especially trees, from school windows, improve test scores for middle school students. 1

Green Schoolyards vary widely, but at their heart they offer natural elements that contribute to a diverse, safe, and welcoming setting for students and staff. (And, again, neighbors. Green Schoolyards enhance neighborhoods.) They may comprise any number of features, but you’ll mainly find that they promote hands-on learning, social-emotional connectivity, and a harnessing of the calming power of nature. Goodness knows, we need to reduce stress and anxiety while fostering confidence and creativity. Green Schoolyards tip that balance toward healthy development.

To learn more about bringing Green Schoolyard thinking to your campus, please keep reading. The contributing authors will showcase examples of projects, features, programs and ideas to transform any school. —JTK

by editor | Mar 17, 2024 | At-risk Youth, Critical Thinking, Data Collection, Environmental Literacy, Equity and Inclusion, IslandWood, Learning Theory, Outdoor education and Outdoor School, Place-based Education, Questioning strategies, Schoolyard Classroom, Teaching Science

At-risk students are exposed to their local environment to gain an appreciation for their community, developing environmental awareness built on knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors applied through actions.

Lindsay Casper and Brant G. Miller

University of Idaho

Moscow, Idaho

Photos by Jessie Farr

n the last day of class, I walked with my students along a local river trail shaded by cottonwood trees and surrounded by diverse plants and animals. The shaded areas provided spots for us to stop, where students assessed the condition of the local river system and the surrounding environment. The class had spent the previous week by the river’s mouth, and the students had grown a connection to the local environment and to each other. This was evident in their sense of ownership of the environment and their lasting relationships, which were expressed as the students discussed what they had learned during the class.

n the last day of class, I walked with my students along a local river trail shaded by cottonwood trees and surrounded by diverse plants and animals. The shaded areas provided spots for us to stop, where students assessed the condition of the local river system and the surrounding environment. The class had spent the previous week by the river’s mouth, and the students had grown a connection to the local environment and to each other. This was evident in their sense of ownership of the environment and their lasting relationships, which were expressed as the students discussed what they had learned during the class.

A month earlier, the class began differently. The students were focused on themselves and their own needs. They stood alone and unwilling to participate. Many expressed feelings of annoyance by being outside, forced to walk and unsure about what to expect in the class. My students were disengaged in their community, education, and the environment. Most had spent little time outside and lacked environmental knowledge and displayed an uncaring attitude toward their local community.

The class included a group of Youth-in-Custody (YIC) students, those who were in the custody of the State (the Division of Child and Family Services, DCFS; and the Division of Juvenile Justice, DJJS), as well as students who are “at-risk” for educational failure, meaning they have not succeeded in other school programs.

Most of my students came from challenging circumstances, with little support for formal educational opportunities, and live in urban areas below the poverty level. Students below the poverty level have fewer opportunities to access nature reserves safely (Larson et al., 2010), and children who live in neighborhoods where they do not feel safe are less likely to readily apply environmental knowledge and awareness to their community (Fisman, 2005).

Despite these setbacks, I wanted to expose my students to their local environment and help them gain an appreciation for their community. I wanted to increase their environmental awareness, built on knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors applied through actions.

The summer education program approached the environmental curriculum via an action-oriented strategy, which takes learning to a level where the class and the outside world integrate with actual practices and address environmental problems (Mongar et al., 2023). The students began to show an understanding of how knowledge can affect their environment and exhibited purpose behind their action. The steps in an action-oriented approach involves students identifying public policy problems, then selecting a problem for study, followed by researching the problem, and developing an explanation, and then finally communicating their findings to others (Fisman, 2005).

Students explored science content, studied sustainable issues, read relevant scientific literature, developed and carried out research, and analyzed data. This multi-step program enabled students to stay active and engaged in environmental science practices and processes, increased their environmental awareness, encouraged them to implement these practices in a real-world environment, and allowed them to immerse in the learning experience. The program developed a connection with environmental restoration, crossed cultural borders and demographic diversity, created a sense of ownership and attachment, and developed a sense of belonging.

Week 1: Invasive Species in Mount Timpanogos Wildlife Management Area

The first week, students monitored a local problem of invasive plants by conducting a field project on vegetation sampling at a wildlife management area. Students researched the area and the issues with the invasive species of cheatgrass. They examined the characteristics that make cheatgrass invasive and used skills to identify local native plants and introduced species in the wilderness. Students determined the problem and used a transect line and percent canopy cover to determine the area’s overall percent cover of cheatgrass. Students used the results of the survey to evaluate the cheatgrass invasion in the area. They compiled their research and presented the issue to local community members to educate and inform them about the possible environmental problems in the area.

Students working in the national forest studying the role of trees in carbon cycling.

Week 2: Carbon Cycling in Uinta-Wasatch-Cache National Forest

During week two, the program evaluated forest carbon cycling within a wilderness area, part of the Uinta-Wasatch-Cache National Forest. The students’ projects involved carbon cycling models and forest carbon sinks to build a comprehensive summary of all the structures and processes involved in trees to help reduce the impact of human activity on the climate. Students identified problems in their local forests by researching the role of forests in carbon sequestration and evaluating climate change. They then selected a problem for the class to study involving the effects of deforestation. Additional research included students discovering how trees sequester carbon and researching how much carbon trees and forests can hold over a given time. Students used their results and data collection to determine how effective trees are for carbon sequestration, compiled their research, and presented the issue to local community members to educate and inform them of the possible environmental problems in deforestation and the need for forested area protection.

Week 3: Jordan River Watershed Management

Week three focused on watershed management, during which students investigated a local river and evaluated its watershed and continued pollution. Students identified problems in their community by reading articles and examining data concerning a local river’s environmental issues, proposed solutions, as well as the progress that has been achieved. Students then made qualitative statements about the river’s current condition based on abiotic and biotic measurements. Students used the information gathered and discussed issues concerning the current quality of the river and discussed why water quality is essential. Students researched the issue by conducting river water quality experiments using flow rate measurements and collected macroinvertebrates. Based on their experimental results, students developed a portfolio with a problem explanation, alternative policies, and a public statement concerning the current Jordan River water quality. Students then presented their findings to community members to help inform and educate them about the river contamination and improvements.

Student collecting water samples.

Week 4: Provo River Delta Restoration Project

During the last week, students examined a river delta restoration project for its effectiveness in restoring a wetland and recovering an endangered fish species. Students investigated the role and importance of river systems and wetland areas, monitored the status of the wetlands, and evaluated the current project’s future effectiveness. Students identified problems in their community by reading articles and examining historical data concerning the lakes environmental issues and made qualitative statements about the lake’s current condition. Students used the information gathered and discussed matters concerning the delta project to protect the local endangered species of June Sucker (Chasmistes liorus). In addition, students toured the construction site and participated in a stewardship activity planting new trees and helping to disperse cottonwood seeds around the area. Based on their stewardship project, a site tour, and experimental results, students developed a portfolio with a problem explanation, alternative policies, and a public statement concerning the current delta restoration project. Students presented their findings to others with the intent to inform and educate them about the project.

Student Impact

This program placed students as critical participants in sustainability and gave them ownership of their education, and knowledge of local environmental issues to give students a deeper appreciation and increased environmental awareness. This curriculum could be adapted for various populations although it is especially essential for those with disadvantaged backgrounds and those underrepresented in science. Creating an opportunity for my students to access nature and build environmental knowledge is important for them to build awareness and an increased ownership of their community. After completing the course, students wrote a reflection on their experience and a summary of what they learned concerning environmental awareness and feelings regarding their connection to nature.

“At first, I hated being outside, but it grew on me, and I had a lot of fun learning about the different invasive species and how they negatively affect the land.”

“I really enjoyed being outside for school. I liked the shaded and natural environments. It was enjoyable and easier to understand because I was learning about everything I could feel and touch.”

“I liked seeing the things we were learning about. It was easier to focus outside.”

Student working on writing assignments during the last day of class.

“I have had a lot of issues with school my whole life. I have never felt like what I was learning was useful. I felt like I was repeating work from former years over and over again and never getting anything out of it. After this experience, I began thinking that maybe the problem wasn’t what we were learning but where we were learning it. It was enjoyable being outside and seeing how what we were learning applied to the world around us. I got to see what we were being taught in action. We did tests with the world and not in a classroom. For the first time, I was really interested in what was being taught, and I realized that the problem wasn’t me.”

The importance of connecting at-risk youth to the outdoors is evident in their reflections. Their reflections indicate an appreciation for being outdoors, a more remarkable ability to focus their attention, and an advantage of learning in the world instead of the classroom. Students’ perception of environmental issues impacts their ability to make educated decisions. The increase in students place identity resulted in a deeper connection to the environment. Their knowledge, attitudes, and actions had changed.

Conclusion

On the last day of class, walking along the river trail with my students, I listened to their conversations, questioned their learning, and gathered their insights. I recognized how the connections made in class developed over time by building relationships, collaboration, trust, and teamwork. My students developed empathy for each other and their environment. As a class, we visited four distinct settings in our local area. My students could grasp the larger perspective by recognizing the cumulative effect of those areas as a whole. They identified the invasive species of cheatgrass studied in week one had made its way downriver and recognized the importance of carbon cycling studied during week two in the cottonwood trees flanking the banks of the river in addition to the value in wetlands studies in week three shown in the progress made on the restoration project. The sequence of each week was purposely built on the following week with a cumulative effort at the river delta restoration project, put in place to help solve many of the environmental issues identified in the previous week’s lessons. This program focuses on increasing student connection and ownership of the environment and identifying how isolated environmental concerns significantly impact the whole ecosystem. Additionally, I wanted my students to notice how environmental restoration and protection alleviate some of these issues. These connections came naturally to the students after the time spent outdoors and investigating environmental issues. Exposing them to new areas and increasing their knowledge and skills affects their awareness.

The environmental science program provided environmental concepts, fostering a deeper appreciation for nature and the outdoors. It engaged all senses, made learning more interactive and memorable, and encouraged more profound connections with the natural world, building ownership of the local area. This program initiated an attachment of students to the local area. It engaged students in environmental issues through science by participating in experiential outdoor education. It kept students engaged with relevant current topics, formed a connection to the natural world, and involved them in direct, focused experiences to increase knowledge, skills, and values.

Lindsay Casper is a graduate student in Environmental Science at the University of Idaho, in Moscow Idaho and teaches Environmental Science to at-risk youth at Summit High School in Utah.

Lindsay Casper is a graduate student in Environmental Science at the University of Idaho, in Moscow Idaho and teaches Environmental Science to at-risk youth at Summit High School in Utah.

Brant G. Miller, Ph.D., is an Associate Professor of Science Education at the University of Idaho. His research interests include Adventure Learning, culturally responsive approaches to STEM education, science teacher education, and technology integration within educational contexts.

Brant G. Miller, Ph.D., is an Associate Professor of Science Education at the University of Idaho. His research interests include Adventure Learning, culturally responsive approaches to STEM education, science teacher education, and technology integration within educational contexts.

The Big Event

The Big Event Applying Their Knowledge

Applying Their Knowledge Edward Merrill Nichols is a 3rd-grade Teacher at North Bay Elementary in North Bend, Oregon. Growing up on the southern coast of Oregon instilled in him a love of and respect for his natural surroundings. With over six years of experience, he fosters student growth through engagement and respect. Edward actively engages in STEM education, leading Professional Development sessions and extracurricular clubs. He holds a Bachelor of Science in Education and a Master of Science in K-8 STEM Education from Western Oregon University.

Edward Merrill Nichols is a 3rd-grade Teacher at North Bay Elementary in North Bend, Oregon. Growing up on the southern coast of Oregon instilled in him a love of and respect for his natural surroundings. With over six years of experience, he fosters student growth through engagement and respect. Edward actively engages in STEM education, leading Professional Development sessions and extracurricular clubs. He holds a Bachelor of Science in Education and a Master of Science in K-8 STEM Education from Western Oregon University. Christina Geierman has taught physics, biology, and dual-credit biology at North Bend High School for eleven years. She is a published scientist, a proud union member, a decent trombone player, and a world traveler. She enjoys spending time outside with her husband, Edward Nichols, and dog, Aine.

Christina Geierman has taught physics, biology, and dual-credit biology at North Bend High School for eleven years. She is a published scientist, a proud union member, a decent trombone player, and a world traveler. She enjoys spending time outside with her husband, Edward Nichols, and dog, Aine.

Abigail M. Harding and Corwyn A. Ellison are environmental educators and graduate students at IslandWood and the University of Washington.

Abigail M. Harding and Corwyn A. Ellison are environmental educators and graduate students at IslandWood and the University of Washington.

n the last day of class, I walked with my students along a local river trail shaded by cottonwood trees and surrounded by diverse plants and animals. The shaded areas provided spots for us to stop, where students assessed the condition of the local river system and the surrounding environment. The class had spent the previous week by the river’s mouth, and the students had grown a connection to the local environment and to each other. This was evident in their sense of ownership of the environment and their lasting relationships, which were expressed as the students discussed what they had learned during the class.

n the last day of class, I walked with my students along a local river trail shaded by cottonwood trees and surrounded by diverse plants and animals. The shaded areas provided spots for us to stop, where students assessed the condition of the local river system and the surrounding environment. The class had spent the previous week by the river’s mouth, and the students had grown a connection to the local environment and to each other. This was evident in their sense of ownership of the environment and their lasting relationships, which were expressed as the students discussed what they had learned during the class.

Lindsay Casper is a graduate student in Environmental Science at the University of Idaho, in Moscow Idaho and teaches Environmental Science to at-risk youth at Summit High School in Utah.

Lindsay Casper is a graduate student in Environmental Science at the University of Idaho, in Moscow Idaho and teaches Environmental Science to at-risk youth at Summit High School in Utah. Brant G. Miller, Ph.D., is an Associate Professor of Science Education at the University of Idaho. His research interests include Adventure Learning, culturally responsive approaches to STEM education, science teacher education, and technology integration within educational contexts.

Brant G. Miller, Ph.D., is an Associate Professor of Science Education at the University of Idaho. His research interests include Adventure Learning, culturally responsive approaches to STEM education, science teacher education, and technology integration within educational contexts.