by editor | Jan 15, 2019 | IslandWood, Marine/Aquatic Education

These students are checking out Blakely Harbor on Bainbridge Island, WA with sight, touch, hearing, and smell. Photo credit: Glassy, 2018

Adventure Hike to a Harbor:

Creating a space for all to engage with marine science

By Julia Glassy

I am currently a graduate student of University of Washington over on Bainbridge Island, WA at IslandWood, a non-profit outdoor education center. I am passionate about adventuring outdoors and marine science education. Interacting with the marine ecosystem allows people of all ages to explore a new ecosystem and grow an appreciation for all that ecosystem provides to the plants and animals who live there and for us, as humans.

What exactly is an adventure hike?

To some it may be walking somewhere with style or awe inspiring activities on the way to a location. While for others it may be getting in a car and driving to a location to check it out and explore. Lastly, an adventure hike could be riding a bus to go out and explore an outdoor space. To me, it is all of the above!

What might one do on adventure hike?

This all depends on the mode of transportation to a waterfront or shoreline and the age of the members going. Games you can play include wind storm (everyone needs to find a tree to hold onto or someone else if they are connected to a tree). Also flash flood (where everyone has to be on higher ground then the caller of the flood). Another game is “I-Spy” where you say “I spy with my little eye something that is blank” and you can fill in the blank. Talking as a group work too!

If in a car, then look out the window and take in the nature outside. Play a couple rounds of “I Spy” with all members in the car.

If on a bus, do what Ms. Frizzle does and make the adventure unique and exciting. Ms. Frizzle is a fictional charismatic 4th grade science teacher who takes her students on unique out-of-this-world field trips via her magic school bus.

Public transportation is an eco-friendly option to get to places that are a little farther away where walking is not an option. Also buses bring people together from all backgrounds, ages, cultures, and economic statuses. Taking a bus might not always be the most direct option, but it sure is the most fun as seen by Ms. Frizzle. It is okay to let the inner child out during these adventure hikes and explore in a new way. Aim for getting to the point of being comfortable with saying “We are on another one of Ms. Frizzle’s crazy class trips!” (Cole, 1995, p. 18). Take ownership over the adventure and be like Ms. Frizzle or like her students.

If visiting a shoreline is not feasible

Visiting your local aquarium:

They will have marine organisms that you can check out up close or hands-on. This hands-on experience is important for children of all ages in order to learn and understand similarities and differences among a variety of ecosystems.

Even if you do not have access locally to a marine or fresh water ecosystem that is okay! Books and films are good resources for learning more about an unfamiliar ecosystem. Reference books and documentaries can be purchased online or in store, but many of them can be checked out at your local library.

Getting more out of a visit to the shoreline

Get familiar with shore and ocean creatures and be a part of an investigation with children or adults you take to the harbor as an adventure hike or school field trip. Investigations do not follow the strict procedure of experiments, but instead are informal ways of wondering and discovering something. An investigation can be done in multiple ways, by taking in observations through sight, hearing, touch, or smell, and making guesses, and asking questions. Taking in observations through the different senses allows someone to become familiar with and gain a sense of place. With this new information, you can gain an appreciation for the place or item that was investigated.

Some books to refer to while familiarizing oneself with shore or ocean habitat depending on age are:

Toddlers:

On the Beach (Smith and Howell, 2003)

Young Readers and Explorers:

In One Tidepool: Crabs, Snails, and Salty Tails (Fredericks, 2002)

Magic School Bus On the Ocean Floor (Cole, 1995)

Ocean (MacQuitty, 2000)

Seashore (Parker, 2000)

Shoreline (Taylor, 1993)

All Ages-Reference:

Beachcombers Guide to Seashore Life in the Pacific Northwest (Sept, 1999)

Activities to do at a Harbor, Shoreline, or Beach

Free Exploration:

Free explorations are where someone takes a few minutes or longer of unstructured time to wander or explore a new space or ecosystem. This unstructured time can reduce all aged students’ distraction level and setup for other activities by allowing students to self-direct their investigations and learning. This is important because it allows students, children, and adults to build confidence, independence, and a greater understanding about the world around them.

Students at IslandWood’s School Overnight Program searching for crabs at Blakely Harbor on Bainbridge Island WA. Photo credit: Glassy, 2018

Crab-itat:

Crab-itats are a fun, hands-on way to explore and learn the important components that crabs need to survive and thrive. One way to make a crab-itat is to use natural materials from the beach you are on to make a habitat for the crabs found there (IslandWood Education Wiki, 2018). The logistics of this project are up to the person making the habitat, and the habitat could take many forms, and be made with several different natural items. Young students and adults can try to add abiotic (non-living) and biotic (living) items to their habitat and then think and describe their reasoning behind the items they chose.

This process of thinking and then explaining the habitat they created allows for the connection to the survival needs of crabs. You can then relate this learning to any animal or plant in other ecosystems. Another important take away from this activity is for someone to gain a sense of place and appreciation for the beach environment. With this new appreciation the person will feel more inclined to take small steps or community action to help take care of the ecosystem so others can enjoy it too!

Investigation:

Step 1: Pick three different locations on the shoreline (ex: sand, rocks, and water’s edge).

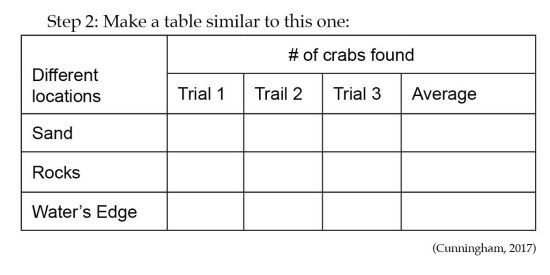

Step 2: Make a table similar to this one:

|

Different

locations |

# of crabs found |

| Trial 1 |

Trail 2 |

Trial 3 |

Average |

| Sand |

|

|

|

|

| Rocks |

|

|

|

|

| Water’s Edge |

|

|

|

|

(Cunningham, 2017)

Step 3: Count the number of crabs at each location. The number of trials is up to you.

Step 4: Calculate average of each location, if you have more than one trial. The average will give an area that crabs are more likely to be, providing evidence for a potential claim. Through this investigation, you can gain knowledge of the preferred habitat of the crabs in your area, make observations, form claims with evidence, and be like a scientist. Investigations are important because you can make them relatable or personal to you and then gain skills that you can use at school, work, or other aspects of your life. You can also look for and investigate sea stars, sea anemones, or snails depending on your personal interests and the beach location near you.

Finding something new to learn more about:

This is similar to free exploration, but instead each person or pair can find something they are interested in and use different tools to explore and learn about it. This includes using a Lummi Loupe (a domed magnifier), small containers, magnifying glasses, and/or reference books. For example, a group of fifth graders I was teaching were excited to go to Blakely Harbor on Bainbridge Island so I brought some small clear containers and some Lummi Loupes to the harbor. Some students were excited about barnacles so we picked up a rock with living, but closed up barnacles on it and put it in one of the containers with saltwater. While still at the beach we observed the barnacles in the container. Also the students used the Lummi Loupes to look at the barnacles up close. We then returned the rock to where we found it and put the saltwater back in Puget Sound. Using the different tools to learn something about the organisms through the use of the four senses (sight, smell, hear, and touch) and then referring to a guide to find out the name of the plant or animal allows for more comprehensive learning and understanding.

Common Animals and Plants Found At the Shoreline

Crabs: Shield-Backed Kelp Crab, Purple Shore Crab, many types of Hermit Crabs (Sept, 1999)

Sea Star: Leather Star, Pacific Blood Star, Purple Star, and many others (Sept, 1999)

Sea Anemones: Giant Green Anemone, Plumose Sea Anemone (Sept, 1999)

Barnacles: Thatched Barnacle, Acorn Barnacle, Goose Barnacle (Sept 1999)

Limpets: Rough Keyhole Limpet, Ribbed Limpet, and more (Sept, 1999)

Chitons: Gumboot Chiton, Woody Chiton, Cooper’s Chiton, and more (Sept, 1999)

Plants On or Near the Shore: Common Sea Lettuce, Bull Kelp, Iridescent Seaweed (Sept, 1999), and Pickleweed

Guidelines for Exploring At the Beach

- Gently roll a rock over to see what is underneath and then return to original state. The rock should be no bigger than the size of your head.

- Be cautious of picking up animals higher than your knee (that is a long way to fall)

- Have a blast exploring the beach and enjoy discovering and learning about something new

Julia Glassy is a current graduate student of University of Washington over on Bainbridge Island, WA at IslandWood. In addition to taking classes, she teaches 3rd through 6th graders who come over to IslandWood from their schools in the greater Seattle and Bainbridge Island area for four days as a part of the School Overnight Program.

Julia Glassy is a current graduate student of University of Washington over on Bainbridge Island, WA at IslandWood. In addition to taking classes, she teaches 3rd through 6th graders who come over to IslandWood from their schools in the greater Seattle and Bainbridge Island area for four days as a part of the School Overnight Program.

References:

Cole, J. (1995). The Magic School Bus On the Ocean Floor. Littleton, MA: Sundance.

Cunningham, Jenny. (Ed.). (2017). IslandWood Field Journal. Bainbridge Island, WA: IslandWood.

Ecosystem in a Box. (n.d.). Retrieved December 6, 2018, from https://wiki.islandwood.org/index.php?title=Ecosytem_in_a_Box

Glassy, Julia. (Photograph). (2018). Blakely Harbor, Bainbridge Island. Bainbridge Island, WA: IslandWood.

Fredericks, A. D. (2002). In One Tidepool: Crabs, Snails, and Salty Tails. Nevada City, CA: Dawn Publications.

MacQuitty, M., Dr. (2000). Ocean. New York: Dorling Kindersley.

Parker, S. (2000). Seashore. New York: Dorling Kindersley.

Sept, J. D. (1999). The Beachcombers Guide to Seashore Life in the Pacific Northwest. Madeira Park, BC: Harbour Pub.

Smith, A., & Howell, L. (2003). On the Beach. Tulsa, OK: EDC Publishing.

Taylor, B. (1993). Shoreline. London: Dorling Kindersley.

by editor | Dec 17, 2018 | IslandWood, Marine/Aquatic Education, Place-based Education

Adventure Hike to a Harbor:

Creating a space for all to engage with marine science

By Julia Glassy

I am currently a graduate student of University of Washington over on Bainbridge Island, WA at IslandWood, a non-profit outdoor education center. I am passionate about adventuring outdoors and marine science education. Interacting with the marine ecosystem allows people of all ages to explore a new ecosystem and grow an appreciation for all that ecosystem provides to the plants and animals who live there and for us, as humans.

What exactly is an adventure hike?

To some it may be walking somewhere with style or awe inspiring activities on the way to a location. While for others it may be getting in a car and driving to a location to check it out and explore. Lastly, an adventure hike could be riding a bus to go out and explore an outdoor space. To me, it is all of the above!

What might one do on an adventure hike?

This all depends on the mode of transportation to a waterfront or shoreline and the age of the members going. Games you can play include wind storm (everyone needs to find a tree to hold onto or someone else if they are connected to a tree). Also flash flood (where everyone has to be on higher ground then the caller of the flood). Another game is “I-Spy” where you say “I spy with my little eye something that is blank” and you can fill in the blank. Talking as a group work too!

If in a car, then look out the window and take in the nature outside. Play a couple rounds of “I Spy” with all members in the car

If on a bus, do what Ms. Frizzle does and make the adventure unique and exciting. Ms. Frizzle is a fictional charismatic 4th grade science teacher who takes her students on unique out-of-this-world field trips via her magic school bus

Public transportation is an eco-friendly option to get to places that are a little farther away where walking is not an option. Also buses bring people together from all backgrounds, ages, cultures, and economic statuses. Taking a bus might not always be the most direct option, but it sure is the most fun as seen by Ms. Frizzle. It is okay to let the inner child out during these adventure hikes and explore in a new way. Aim for getting to the point of being comfortable with saying “We are on another one of Ms. Frizzle’s crazy class trips!” (Cole, 1995, p. 18). Take ownership over the adventure and be like Ms. Frizzle or like her students.

If visiting a shoreline is not feasible

Visiting your local aquarium:

They will have marine organisms that you can check out up close or hands-on. This hands-on experience is important for children of all ages in order to learn and understand similarities and differences among a variety of ecosystems.

Even if you do not have access locally to a marine or fresh water ecosystem that is okay! Books and films are good resources for learning more about an unfamiliar ecosystem. Reference books and documentaries can be purchased online or in store, but many of them can be checked out at your local library.

Getting more out of a visit to the shoreline

Getting more out of a visit to the shoreline

Get familiar with shore and ocean creatures and be a part of an investigation with children or adults you take to the harbor as an adventure hike or school field trip. Investigations do not follow the strict procedure of experiments, but instead are informal ways of wondering and discovering something. An investigation can be done in multiple ways, by taking in observations through sight, hearing, touch, or smell, and making guesses, and asking questions. Taking in observations through the different senses allows someone to become familiar with and gain a sense of place. With this new information, you can gain an appreciation for the place or item that was investigated.

Some books to refer to while familiarizing oneself with shore or ocean habitat depending on age are:

Toddlers:

On the Beach (Smith and Howell, 2003)

Young Readers and Explorers:

In One Tidepool: Crabs, Snails, and Salty Tails (Fredericks, 2002)

Magic School Bus On the Ocean Floor (Cole, 1995)

Ocean (MacQuitty, 2000)

Seashore (Parker, 2000)

Shoreline (Taylor, 1993)

All Ages-Reference:

Beachcombers Guide to Seashore Life in the Pacific Northwest (Sept, 1999)

Activities to do at a Harbor, Shoreline, or Beach

Free Exploration

Free explorations are where someone takes a few minutes or longer of unstructured time to wander or explore a new space or ecosystem. This unstructured time can reduce all aged students’ distraction level and setup for other activities by allowing students to self-direct their investigations and learning. This is important because it allows students, children, and adults to build confidence, independence, and a greater understanding about the world around them.

Crabitat

Crab-itats are a fun, hands-on way to explore and learn the important components that crabs need to survive and thrive. One way to make a crab-itat is to use natural materials from the beach you are on to make a habitat for the crabs found there (IslandWood Education Wiki, 2018). The logistics of this project are up to the person making the habitat, and the habitat could take many forms, and be made with several different natural items. Young students and adults can try to add abiotic (non-living) and biotic (living) items to their habitat and then think and describe their reasoning behind the items they chose.

This process of thinking and then explaining the habitat they created allows for the connection to the survival needs of crabs. You can then relate this learning to any animal or plant in other ecosystems. Another important take away from this activity is for someone to gain a sense of place and appreciation for the beach environment. With this new appreciation the person will feel more inclined to take small steps or community action to help take care of the ecosystem so others can enjoy it too!

Investigation

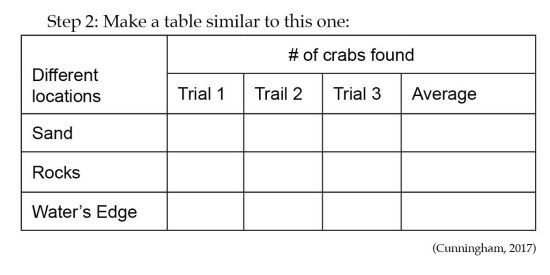

Step 1: Pick three different locations on the shoreline (ex: sand, rocks, and water’s edge).

Step 1: Pick three different locations on the shoreline (ex: sand, rocks, and water’s edge).

Step 2: Make a table similar to this one

(Cunningham, 2017)

Step 3: Count the number of crabs at each location. The number of trials is up to you.

Step 4: Calculate average of each location, if you have more than one trial. The average will give an area that crabs are more likely to be, providing evidence for a potential claim. Through this investigation, you can gain knowledge of the preferred habitat of the crabs in your area, make observations, form claims with evidence, and be like a scientist. Investigations are important because you can make them relatable or personal to you and then gain skills that you can use at school, work, or other aspects of your life. You can also look for and investigate sea stars, sea anemones, or snails depending on your personal interests and the beach location near you.

Finding something new to learn more about

This is similar to free exploration, but instead each person or pair can find something they are interested in and use different tools to explore and learn about it. This includes using a Lummi Loupe (a domed magnifier), small containers, magnifying glasses, and/or reference books. For example, a group of fifth graders I was teaching were excited to go to Blakely Harbor on Bainbridge Island so I brought some small clear containers and some Lummi Loupes to the harbor. Some students were excited about barnacles so we picked up a rock with living, but closed up barnacles on it and put it in one of the containers with saltwater. While still at the beach we observed the barnacles in the container. Also the students used the Lummi Loupes to look at the barnacles up close. We then returned the rock to where we found it and put the saltwater back in Puget Sound. Using the different tools to learn something about the organisms through the use of the four senses (sight, smell, hear, and touch) and then referring to a guide to find out the name of the plant or animal allows for more comprehensive learning and understanding.

Common Animals and Plants Found At the Shoreline

Crabs: Shield-Backed Kelp Crab, Purple Shore Crab, many types of Hermit Crabs (Sept, 1999)

Sea Star: Leather Star, Pacific Blood Star, Purple Star, and many others (Sept, 1999)

Sea Anemones: Giant Green Anemone, Plumose Sea Anemone (Sept, 1999)

Barnacles: Thatched Barnacle, Acorn Barnacle, Goose Barnacle (Sept 1999)

Limpets: Rough Keyhole Limpet, Ribbed Limpet, and more (Sept, 1999)

Chitons: Gumboot Chiton, Woody Chiton, Cooper’s Chiton, and more (Sept, 1999)

Plants On or Near the Shore: Common Sea Lettuce, Bull Kelp, Iridescent Seaweed (Sept, 1999), and Pickleweed

Guidelines for Exploring at the Beach

- Gently roll a rock over to see what is underneath and then return to original state. The rock should be no bigger than the size of your head.

- Be cautious of picking up animals higher than your knee (that is a long way to fall)

- Have a blast exploring the beach and enjoy discovering and learning about something new

Julia Glassy is a current graduate student of University of Washington over on Bainbridge Island, WA at IslandWood. In addition to taking classes, she teaches 3rd through 6th graders who come over to IslandWood from their schools in the greater Seattle and Bainbridge Island area for four days as a part of the School Overnight Program.

Julia Glassy is a current graduate student of University of Washington over on Bainbridge Island, WA at IslandWood. In addition to taking classes, she teaches 3rd through 6th graders who come over to IslandWood from their schools in the greater Seattle and Bainbridge Island area for four days as a part of the School Overnight Program.

References

Cole, J. (1995). The Magic School Bus On the Ocean Floor. Littleton, MA: Sundance.

Cunningham, Jenny. (Ed.). (2017). IslandWood Field Journal. Bainbridge Island, WA: IslandWood.

Ecosystem in a Box. (n.d.). Retrieved December 6, 2018, from https://wiki.islandwood.org/index.php?title=Ecosytem_in_a_Box

Glassy, Julia. (Photograph). (2018). Blakely Harbor, Bainbridge Island. Bainbridge Island, WA: IslandWood.

Fredericks, A. D. (2002). In One Tidepool: Crabs, Snails, and Salty Tails. Nevada City, CA: Dawn Publications.

MacQuitty, M., Dr. (2000). Ocean. New York: Dorling Kindersley.

Parker, S. (2000). Seashore. New York: Dorling Kindersley.

Sept, J. D. (1999). The Beachcombers Guide to Seashore Life in the Pacific Northwest. Madeira Park, BC: Harbour Pub.

Smith, A., & Howell, L. (2003). On the Beach. Tulsa, OK: EDC Publishing.

Taylor, B. (1993). Shoreline. London: Dorling Kindersley.

by editor | Oct 26, 2015 | Place-based Education

Combining the Strengths of Adventure Learning and Place-based Education

How re-conceptualizing the role of technology in place-based education enhances place responsive pedagogies through technology.

by R. Justin Hougham,

Karla C. Bradley Eitel and

Brant G. Miller

University of Idaho

Technology in Place-based Environmental Education

In the 21st century, students need to be able to communicate through a variety of mediums, be critical consumers of vast amounts of written and visual data, and possess skills and dispositions for addressing complex global issues with local implications, such as climate change. As practitioners of residential place-based environmental education that seeks to foster scientific literacy and connect students to place, we have traveled cautiously into the cyber-enabled landscape because of a deeply rooted feeling that technology can be a distraction to students’ deep observation in the field. That said, we are exploring the idea that technology may also provide tools that can transform our ability to connect students to place. Imagine this scenario: a field teacher uses a picture to show students a concept diagram of the water cycle; the students’ attention is on the image rather than on the place. Instead, what if cameras were used to observe water in the immediate environment, thus, cataloging water in as many phases as the students can find? Digital voice recorders could be employed to capture the haunting, ancient whale-like sounds of liquid water beneath the frozen lake; In addition, students collect and upload data about the quality or quantity of the water. This data could then be visualized within an observational database used by scientists to better understand water resources at a hyper-local scale, thereby contributing to better predictive models that inform watershed and fisheries management. In the first scenario, an age-old “technology” distracts from deep observation, but in the re-imagined scenario observation is enhanced and transformed.

It is our belief that, when used wisely, technology can enable a deeper connection to material through a multi-media approach to observing, describing places, and visualizing data collected on site. 21st century educators are increasingly being asked to integrate cyber-based tools into programs and we propose that they do so in a way that increases students’ ability to explore the socio-ecological places where they live. One way of doing this is through the AL@ approach.

Merging Technology, Place and Change

Merging Technology, Place and Change

AL@ is a re-conceptualization of the role of technology in place-based education that enhances place responsive pedagogies through technology. Adventure Learning (AL) is a hybrid online curricular approach we have explored within the context of a residential environmental education program at the McCall Outdoor Science School (MOSS). We are naming this combined theoretical frameworks of AL and PBE, Adventure Learning @ (AL@). The AL@ nomenclature is intended to express at once the online world (@) as well as the treatment offered here of AL that situates the framework in relation to the principles of PBE (as in Adventure Learning at…). Students and teachers become experts in their own experiences through studies of the places where they live, using freely available software and low cost technology. Further, we explore ways in which AL@ enhances our place-based programs by supporting connection and communication beyond the spatial and temporal boundaries of student experience. Finally, by students authoring their experience, honoring multiple world views, the hybridized approach offered through AL@ equips students and teachers to engage in experiential education that is decolonizing STEM education as well as technology in education.

Place-Based Education

Place-based education (PBE) provides an important foundation for bringing place to the forefront of student inquiries. In the book Place-Based Education, Sobel (2004) states that place-based pedagogy:

helps students develop stronger ties to the community, enhances students’ appreciation for the natural world, and creates a heightened commitment to serving as active, contributing citizens (p.7).

Sobel (2004) advocates developing curricula that are relevant, authentic and evolved from the particular context in which it is used. A central characteristic and distinguishing feature of place-based education is that it aims to break down artificial constructs and barriers like the distinction between school and community, and nature and humanity (Smith, 2002). While this pedagogy is being widely embraced, iterations of PBE lack effective strategies that connect the place experience to other venues or digitally. There is much room to explore how PBE can effectively leverage the power of experiences with the potential of technology and digital media. An enhanced AL model, found in AL@, can begin to fill this gap.

Adventure Learning @

AL is a hybrid distance education approach that provides students with opportunities to explore real-world issues through authentic adventure-based learning experiences within both face-to-face and online collaborative learning environments (Doering, 2006, 2007; Doering & Veletsianos, 2008; Veletsianos & Kleanthous, 2009). As an approach to designing learning environments, AL has been found to motivate students (Moos & Honkomp, 2011) and inspire meaningful collaborations and inquiries for students and teachers (Doering & Veletsianos, 2008; Veletsianos & Doering, 2010).

AL@ presents a powerful new approach for teaching and learning that builds upon earlier adventure learning efforts. In this reimagined model bringing to bear the intersection of PBE and AL, we envision a novel context for teaching and learning about places through technology-rich curricula. AL@ enables students to explore local places through physical experiences as well as through digital media, geospatial technologies, and online collaboration. Through the intersection of PBE and AL in AL@ we believe that each can reciprocally enhance the other. Four key distinctions in the AL@ approach include student generated knowledge, focused on local observation, smaller scale, and interconnected expeditions.

1. Students are generators and not just consumers of knowledge

The archetype model of AL positioned distant adventurers as holders and creators of knowledge. We have wondered if highlighting the experience of distant adventurers and associated content experts has undermined students’ evaluation of their own ability to generate meaningful understanding about things that matter to them. The hidden curriculum can be that students’ own experience is not as important as the experiences of scientists and adventurers that they see represented in popular media and curricular enhancements that use this “scientist /adventurer as rock star” model.

By rethinking the AL approach to position students and teachers as “experts in their own experiences,” the AL@ approach has the potential to transform the way students and teachers think of themselves with respect to being scientists, problem solvers and contributors to knowledge about their communities. The coherent narratives created around local spaces are expected to transform students’ experience of “doing science” from an abstract exercise to one in which they understand the purpose of their scientific inquiry. Thus, student inquiries are driven by their own questions and relevant to local surroundings. By defining problems of local interest, and working with experts with local knowledge who have connections to the community, students and teachers come to think of themselves as experts, scientists, and problem solvers within their own places.

2. AL@ is focused on deep observation of local places

Building reflection skills is a core tenet of PBE, and an important step in the progression towards an engaged and active citizenry. Wattchow and Brown assert (2011) that place as a conceptual frame is an important pedagogy as it “provides rich potential for outdoor educators who are already well-versed in experiential methodologies. A participant learning about the significance of a place, and how their beliefs and actions impact upon it, will be well positioned to reflect on how their community may need to adapt to the challenges ahead (p. ix).”

The richness of a grounded experience and inquiry in place lays the foundation for meaningful reflection that takes place in the digital environment. The digitized reflection is then available to a network of students locally and globally. The AL@ approach turns the narrative into a conversation rather than a story being told by someone else. By doing so, students contribute valuable perspectives to conversations about natural resources, local observations, and the nature of science.

3. Expeditions for all

Early iterations of AL have sent a team of scientists and explorers to remote places with reports back to classrooms across the world. It is our estimation that this approach is limiting. The logistical complexity and high-end equipment required can make conducting an expedition unattainable for all but the most highly resourced schools. In promoting the use of relatively inexpensive and simple to use media collection devices (e.g. digital cameras), the barriers to participation in AL@ are negligible. Considering the audience, location, and the science along the way, media products are assembled to represent each component of the system. Guidelines for teachers and students for the practical enactment of the AL@ approach includes: collecting media that can be shared easily with limited editing via the online environment, and considerations for audience, place and science.

4. Multiple interconnected expeditions are focused on thematic questions

Through a digital learning website hub, students and teachers have the opportunity to be part of a larger AL@ community. One objective of this robust media environment is to cultivate a flourishing upload and download culture between stakeholders-students, teachers, parents-and across disciplines. Archival of media products and data generated is essential, representing exciting information that will be accessible to participants for future content inquiries. Members of the education community will drive the integration of this material into the curriculum as it serves them

The combined strengths of AL and PBE create new spaces for and means of connecting to place, generating knowledge and creatively solving problems. We believe that AL@ as a pedagogy offers an approach to virtual and physical environments that can enrich local and global connections to-and between-places. Where Smith (2002) points to PBE dissolving the artificial barriers between school and community, and nature and humanity; AL@ adds the capacity to transcend the false dichotomy of global and local.

Practical enactment of AL@MOSS

Practical enactment of AL@MOSS

An example of applied AL@ principles is seen in the McCall Outdoor Science School (AL@MOSS). A program of the University of Idaho, the mission of the McCall Outdoor Science School (MOSS) is to facilitate place-based, collaborative science inquiry within the context of Idaho’s land, water and communities-getting people outdoors to learn about science, place and community. Located in the Payette watershed on Payette Lake in McCall, ID, the school and its partners foster scientific literacy, sense of place, active lifestyles and community skills through graduate and professional education, youth science programs, seminars, conferences, and leadership development initiatives. MOSS provides experiential learning opportunities for and among students, educators, scientists and citizens with the goal of fostering the critical thinking skills and sense of ownership necessary to address complex problems.

Students and teachers come to MOSS from across the state of Idaho for three to ten day experiences to study the natural history of the local environment, build deeper connections with their peers through team building challenges, meet scientists, participate in local service projects and engage in developing and conducting their own field-based scientific inquiries. An on-site graduate residency program engages aspiring environmental educators in coursework related to understanding the local ecological and social environment, developing leadership skills and learning about place-based pedagogies while they are serving as field instructors in residential and school-based K-12 programs. It is in this environment that the AL@ model is being explored to transform student connectivity to place and each other, no matter where they are. Numerous similar institutions exist throughout the world; this model has the potential to inform their curricula and programs as well.

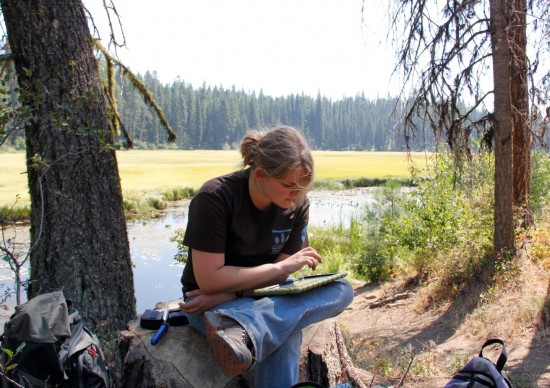

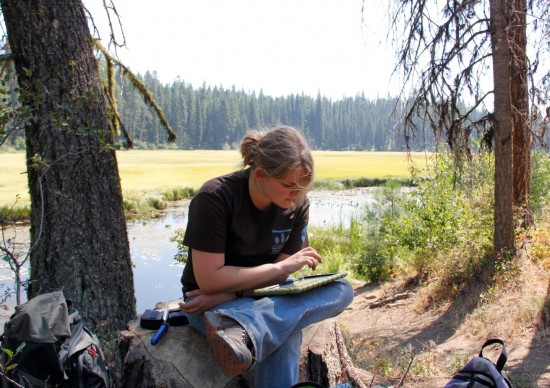

What does AL@MOSS look like? Imagine a group of middle school students studying water quality on a lake that they have known their whole lives. They start by talking about their memories of visiting this lake with their families, next they are guided to create a drawing that imagines the lake as it was 10,000 years ago, and as it will be 10,000 years in the future. They collect macro-invertebrates, measure the dissolved oxygen, pH, turbidity and nitrates. They look up at the mountains that surround the lake and envision how the snowpack becomes a reservoir from November through April, before its water begins run-off in May or June. As students conduct this place-based investigation of the watershed, they take pictures as they complete their data collection and carefully enter their data into field journals and an online database, accessed using an iPad in the field. A digital video recording captures a student’s reflections and inferences on how predicted changes in precipitation might impact the quantity of water that is available for various water users. When they return to “base camp”, these written reflections, photographs and videos are uploaded to a site where students from other communities can read and respond to their observations online. Student and teachers interested in water as a place responsive topic then have a videoconference with a local scientist who is studying changes in precipitation patterns due to climate change, a farmer who might be impacted by a change in the timing of available water, and a fisheries biologist who talks about how fish might be impacted. They finish the day by going back outside to play a game that simulates the highlights of the interconnected nature of relationships within the Earth systems.

Where will you AL@?

The promise of what AL and PBE bring to each other through AL@ is found through a democratized learning environment which becomes a digital commons. Community members, parents, learners and educators are all engaged in essential 21st century skills. By communicating digitally, participants are able to see how information of near and distant spaces is interrelated. The AL@ approach supports multiple worldviews through the invitation to engage in a process that sharpens expertise in our own experience. Equipped with AL@, educators and learners can meaningfully explore what place means through sharing their experiences. Through observation, reflection, and artifact keeping the AL@ approach supports knowledge keepers across the past, present and future narratives of places that can be connected. Highlighting relationships and breaking down spatial boundaries can serve to strengthen our understanding of the ways in which we are all connected.

Communicating Success

In the AL@MOSS approach, assessment is an important tool that we use to shape our curriculum and our delivery of programming. Content specific assessments of student learning are administered in each program session, with topics ranging from water resources and a changing climate to energy literacy and biofuels. Science identity is another research area explored in assessments in this program.

Additionally, artifacts are collected from the students experiences out in the forest, in the snow, out on the lake or on the mountain. These artifacts help us capture and communicate the success of our approach- and invite support from the network that students have in the community, including teachers, classmates, parents, and friends. These artifacts include video, pictures, and images of student work that are available in near real-time, but also archived for student portfolios that can demonstrate development in communication skills as well as progress in content areas.

R. Justin Hougham is a Post Doctoral Fellow at the University of Idaho, Department of Geography. Karla Eitel is the Director of Education at the University of Idaho McCall Outdoor Science School, College of Natural Resources. Brant G. Miller is an Assistant Professor of Science and Technology Education at the University of Idaho College of Education.

References

Doering, A. (2006). Adventure learning: Transformative hybrid online education. Distance Education, 27(2), 197-215.

Doering, A. (2007). Adventure learning: Situating learning in an authentic context. Innovate-Journal of Online Education, 3(6). Retrieved on August 30, 2008 from http://innovateonline.info/index/php?view=article&id=342.

Doering, A., & Veletsianos, G. (Fall 2008). Hybrid Online Education: Identifying Integration Models using Adventure Learning. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 41(1), 101-119.

Hutchison, D. (1998). Growing up green: Education for ecological renewal. New York: Teachers College Press.

Orr, D. W. (2004). Earth in mind: On education, environment, and the human prospect. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Smith, G.A. (2002). Going local. Educational Leadership, 60(1), 30-33.

Smith, G. A. (2007). Place-based education: breaking through the constraining regularities of public school. Environmental Education Research, 13(2), 189-207. doi:10.1080/13504620701285180

Sobel, D. (2004). Place-based education: Connecting classrooms & communities. Great Barrington, MA: The Orion Society

The Learning Technologies Collaborative (2010). “Emerging”: A re-conceptualization of contemporary technology design and integration. In Veletsianos, G. (Ed.), Emerging Technologies in Distance Education (pp. 91-107). Edmonton, AB: Athabasca University Press.

Veetsianos, G., & Kleanthous, I. (2009). A review of adventure learning. The International Review Of Research In Open And Distance Learning, 10(6), 84-105.

Watchow and Brown (2011). A pedagogy of place: Outdoor education for a changing world (p. IX). Victoria, Australia: Monash University Publishing.

Woodhouse, J.L., and Knapp, C.E. (2000). Place-based curriculum and instruction: Outdoor and environmental education approaches. ERIC Clearinghouse on Rural Education and Small Schools.

Julia Glassy is a current graduate student of University of Washington over on Bainbridge Island, WA at IslandWood. In addition to taking classes, she teaches 3rd through 6th graders who come over to IslandWood from their schools in the greater Seattle and Bainbridge Island area for four days as a part of the School Overnight Program.

Julia Glassy is a current graduate student of University of Washington over on Bainbridge Island, WA at IslandWood. In addition to taking classes, she teaches 3rd through 6th graders who come over to IslandWood from their schools in the greater Seattle and Bainbridge Island area for four days as a part of the School Overnight Program.