by editor | Jan 16, 2024 | Environmental Literacy, IslandWood, K-12 Activities, K-12 Classroom Resources, Learning Theory

by Zachary Zimmerman

Bainbridge Island, WA

s an outdoor educator, I often get sucked into the false binary that lessons are either fun or informative, that content must be sweetened with games, stories, and activities like applesauce for children’s medicine. But stories are one of the oldest forms of teaching known to humankind, and games and interactive activities help students interpret and internalize what they learn on trails, in classrooms, and at home. In this article, I invite you to stop apologizing for your content teaching and start weaving it into lesson sequences that include stories, games, writing activities, and more. Sequences can make your teaching practices more effective, more equitable, and yes, more fun.

s an outdoor educator, I often get sucked into the false binary that lessons are either fun or informative, that content must be sweetened with games, stories, and activities like applesauce for children’s medicine. But stories are one of the oldest forms of teaching known to humankind, and games and interactive activities help students interpret and internalize what they learn on trails, in classrooms, and at home. In this article, I invite you to stop apologizing for your content teaching and start weaving it into lesson sequences that include stories, games, writing activities, and more. Sequences can make your teaching practices more effective, more equitable, and yes, more fun.

Recently, I learned that teachers visiting Islandwood with their students were passing on the same feedback week after week: many of the lessons our instructors were teaching on ecosystems fell short because students didn’t fully understand what the word “ecosystem” meant. They might be able to give examples (“rainforest”) or describe them somewhat (“habitat”), but they were missing the definition and significance: communities of different living things that interact with each other and their physical habitats. An ecosystem isn’t just a place; it’s a dynamic arrangement of matter and energy; sunlight, water, and nutrients; life, death, and life again. Of course it needs some scaffolding

Because ecosystems are one of my favorite things to teach 5th graders, I took note immediately. Learning about ecosystems helps students understand the world in which they live, sets the stage for deeper sense-making outdoors, and aligns neatly with NGSS standards and cross-cutting concepts. Ecosystems are also teachers themselves, offering lessons on diversity, interdependence, resilience, and identity. When students see forests and intertidal zones as neighborhoods full of unique and diverse beings supporting each other through their mere existence, they may have an easier time valuing their own identities and thinking more about how they fit into their communities. To restate ecologically, they may discover their own niche.

As heady and enticing as these ideas are to me, I know that teaching for equity means letting go of preconceived notions of how students will use my lessons, and creating space and support for them to connect ideas presented in class to their own lives. It also means ensuring that all students are working from the same baseline of knowledge as they explore those more abstract spaces. In the past, I had equated “baseline” with “lecturing” and “lecturing” with “boring”, leading me to approach core content apologetically and half-heartedly.

To address my reluctance and reimagine content teaching as a part of, not apart from, the immersive fun and exploration that drew me to outdoor education, I started experimenting with lesson sequencing: using stories, activities, and games to bookend and contextualize core concepts. What started as an apologetic approach to content has proven an effective and equitable strategy for outdoor teaching that makes complex ideas like ecosystems meaningful, memorable, and fun. Below I outline a favorite lesson sequence on ecosystems that envelopes content with storytelling and modeling activities. But first, a few tips for developing your own sequences.

Work Backwards

Mapping the core concepts you need to scaffold into a larger lesson can reveal where your content time will best be spent. In the ecosystem example below, I use worksheets to get all my students on the same page about producers, consumers, and decomposers: what they are, what they need, and how they relate to each other. Knowing which concepts I need to teach about can also help me select starting lessons that introduce relevant terms or relationships.

Know Your Audience

Are your students quiet or chatty? Do they like individual reflections, pair-shares, or large group discussions? Maybe a combination? Do they ask a lot of questions, or wait for you to give answers? Do any of your students have IEPs or 504 plans? What other accommodations might one or many students need to feel safe, comfortable, and ready to learn and participate? Consider these questions when thinking about your group and reflect on how they might impact your plan. Maybe you need to switch out that starting story for a running game; maybe that running game works equally well walking or sitting.

Find Your Flow

Once you know what information, structure, and supports your students need to reach their learning targets, think about an order of operations that makes sense for the spaces you’ll be teaching, your style, and the energy you expect. Thinking about biorhythms can be a helpful clue here – if you’re starting this module right after lunch, will students be more or less active than if you began your morning with it? There’s no perfect formula here, but Ben Greenwood’s Lesson Arc (Introduction, Exploration, Consolidation) provides helpful inspiration. Personally, I like to start with something engaging that models the ideas we’ll use and end with a game or reflective activity – again, this is where art meets science, so get creative.

Now that you have some ideas for sequencing lessons, let’s look at an example.

Lesson Sequence: Ecosystems and Interdependence

Materials:

- Storybook

- Ecosystem worksheets (Islandwood journal is used in this example)

- Ecosystem cards (make your own or find publicly available regional sets like this one from Sierra Club British Columbia)

- Ball of string or twine

- Writing untensils

Lesson 1: Read The Salamander Room by Anne Mazer (read-along here

This is the story of a young boy who brings home a salamander to live in his room. As his mother continues to inquire about how the boy will care for the salamander (and eventually, to care for everything else he has added to his room in the process), students begin to see not only how different living things rely on each other, but the impacts of removing a more-than-human friend from its chosen home.

Additional discussion questions:

- How did the room change throughout the story?

- What else would you have changed?

- What relationships did you notice?

(Of course, any storybook of your choosing that describes habitats, food webs, nutrient/energy cycles, and interconnectivity will work – I just like this one!).

Lesson 2: Ecosystem Components and Definitions

Transitioning into the content component, begin by asking students if they have ever heard of the word “ecosystem” and what it means. While assessing answers, ask whether they saw an ecosystem in the story they heard. These discussions can help decenter the instructor as the holder of knowledge and assess potential leaders in your group.

Next, pass out worksheets/journals and give students 5-10 minutes to complete the assigned pages, encouraging them to quietly work alone or in small groups. Set clear expectations that they should do their best to fill out whatever they know, and that we’ll fill them out together as a group afterward.

Drawings from a student’s Islandwood journal. Mushrooms are depicted as decomposers, trees as producers, and squirrels as consumers. On the next page, sentence and word starters help students decode core definitions.

When students indicate that they are done, invite them back to a large group. Ask if anyone can give definitions of producers, consumers, and decomposers, or share examples that they drew or wrote in their journals. This helps individual students confirm or correct their answers without judgment and add test their knowledge by adding their own examples to the discussion. Talking through producer growth, animal consumption, and decomposition a few times helps reinforce how different inputs and outputs relate to the process and emphasizes its cyclical nature.

When students have completed their worksheets and all questions have been answered, move on to Lesson 3.

Lesson 3: Web of Life (adapted from Sierra Club British Columbia)

Because a full lesson plan is linked above, I focus here on ways that I consolidate knowledge from the above lessons, assess content learning, and prepare students to apply these new ideas to future exploration.

Pass out Web of Life cards to your students and save one for yourself. If you plan to introduce a new element later (e.g. birds migrating from habitat loss or new trees planted by conservationists), hold onto those cards.

As you pass out cards, ask students to take a moment and acquaint themselves with their element. Some questions you might ask:

- Are they a producer, decomposer, consumer, or something abiotic?

- What do they know about this element?

- What does this element need to thrive?

- What threatens it?

When students are ready, begin the lesson as described in the linked plan. Empower students to help correct or add to others’ ideas. For example, if a student assigned “worm” passes to “soil” and says, “I relat to soil because I eat it,” invite the group to discuss what they know about how worms relate to soil or how they get their energy (i.e. decomposition, which makes soil).

Once the web is fully developed, you can take this lesson in many directions, inviting students to consider what happens when one part of the web is removed or changed. When they can see that everything is connected, even indirectly, you’re ready to explore ecosystems!

Zachary Zimmerman (he/him) is an outdoor educator, teacher training facilitator, and insatiable problem-solver residing on the traditional Suquamish/Coast Salish land currently known as Bainbridge Island

Sources Cited

5-LS2-1 Ecosystems: Interactions, Energy, and Dynamics | Next Generation Science Standards. (n.d.). Retrieved May 25, 2023, from https://www.nextgenscience.org/pe/5-ls2-1-ecosystems-interactions-energy-and-dynamics

Greenwood, B. (n.d.). What is Lesson Sequencing and How Can it Save You Time? Retrieved May 25, 2023, from https://blog.teamsatchel.com/what-is-lesson-sequencing-and-how-can-it-save-you-time

Mazer, Anne., & Johnson, S. (1994). The Salamander Room (1st Dragonfly Books ed.). Knopf

Sierra Club BC. (n.d.). Web of Life. Sierra Club BC. Retrieved May 25, 2023, from https://sierraclub.bc.ca/wp-content/uploads/Web-of-Life-Game.pdf

by editor | Jan 27, 2020 | Equity and Inclusion, Outdoor education and Outdoor School

Providing opportunities for students of color to explore

the outdoors and science careers

Text and photos by Sprinavasa Brown

recall the high school science teacher who doubted my capacity to succeed in advanced biology, the pre-med advisers who pointed my friend Dr. Kellianne Richardson and me away from their program and discouraged us from considering a career in medicine – biased advice given under the guise of truth and tough love.

recall the high school science teacher who doubted my capacity to succeed in advanced biology, the pre-med advisers who pointed my friend Dr. Kellianne Richardson and me away from their program and discouraged us from considering a career in medicine – biased advice given under the guise of truth and tough love.

I remember only three classes with professors of color in my four years at college, only one of whom was a woman. We needed to see her, to hold faith that as women of color, we were good enough, we were smart enough to be there. We were simply enough, and we had so much to contribute to medicine, eager to learn, to improve and to struggle alongside our mostly White peers at our private liberal arts college.

These are the experiences that led Kellianne and me to see the need for more spaces set aside for future Black scientists, for multi-hued Brown future environmentalists.

The story of Camp ELSO (Experience Life Science Outdoors) started with our vision. We want Black and Brown children to access more and better experiences than we did, experiences that help them see their potential in science, that prepare them for the potentially steep learning curve that comes with declaring a science major. We want Black and Brown kids to feel comfortable in a lab room, navigating a science library, and advocating for themselves with faculty and advisers. We hope to inspire their academic pursuits by laying the foundation with curiosity and critical thinking.

Creating a sense of belonging

Camp ELSO’s Wayfinders program is our main program for youths in kindergarten through sixth grade. What began as a programmatic response to our community needs assessment – filling the visible gap in accessible, affordable, experiential science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) programs for young Black and Brown children – quickly grew into a refuge space for youth of greater Portland. Wayfinders is all about creating a safe uplifting and affirming space for youth to engage in learning around four key areas: life science, ecology, community and cultural history. While our week-long sessions include field trip sites similar to many mainstream environmental education programs, our approach is sharply focused on grounding the youth experience in environmental justice while elevating the visibility and leadership opportunities for folks of color.

We are creating a special place for Black and Brown youth to have transformative experiences, to create memories that we hope will stick with them until adulthood. Creating such a space comes with difficulties, the type of challenges that force our leadership to make tough decisions that we believe will yield the best outcomes for youth underrepresented in STEM fields. For instance, how to mitigate the undertones of colonization, nationalism, and co-opting of traditional knowledge – harmful practices ingrained in mainstream environmental education.

We are creating a special place for Black and Brown youth to have transformative experiences, to create memories that we hope will stick with them until adulthood. Creating such a space comes with difficulties, the type of challenges that force our leadership to make tough decisions that we believe will yield the best outcomes for youth underrepresented in STEM fields. For instance, how to mitigate the undertones of colonization, nationalism, and co-opting of traditional knowledge – harmful practices ingrained in mainstream environmental education.

To do so, we invest in training young adults of color to lead as camp guides. We provide resources to support them in developing the skills necessary to engage youth of diverse ethnicities, backgrounds, socioeconomic status and family structure. Our guides practice taking topics and developing discussion questions and lesson plans that are relevant and engaging. We know that the more our staff represents the communities we serve, the closer we get to ensuring that Camp ELSO programming is responsive to the needs of children of color, authentic to their lived experience, and is a reflection of the values of our organization and community.

In 2019 nearly 100 children of color from greater Portland will participate in Camp ELSO’s Wayfinders program over spring and summer break, spending over 40 hours in a week-long day camp engaging in environmental STEM learning and enjoying the outdoors. We reach more children and families through our community outreach events like “Introduce a Girl to Engineering Day: Women of Color Panel” and “Endangered Species Day: Introduction to Youth Activism.”

The most critical aspects of our Wayfinders program happens even before we welcome a single child through our doors. With the intent of purifying the air and spirit, we smudge with cedar and sage to prepare the space. When a child shows up, they are greeted by name. We set the tone for the day with yoga and affirmations to the sounds of Stevie Wonder and Yemi Alade as we strive to expose our kids to global music from diverse cultures.

We have taken the time to ask parents thoughtful questions in the application process to help us prepare to welcome their child to our community. We have painstakingly selected what we feel is a balanced, blended group of eager young minds from diverse ethnic backgrounds: Black, Latinx, the children of immigrants, multi and biracial children of various ethnicities, fuego and magic. Our children come from neighborhoods across Portland and its many suburbs. They come from foster care, single-parent households, affluent homes, homes where they are adopted into loving and beautifully blended families, strong and proud Black families, and intergenerational households with active grandmas and aunties. Consistent with every child and every household is an interest and curiosity around STEM, a love of nature and the outdoors.

The children arrive full of potential and the vitality of youth. Some are shy, and nerves are visible each morning. By the end of the week we’ve built trust and rapport with each of them, we’ve sat in countless circles teaching them our values based in Afrocentric principles, values selected by previous camp guides representing the youth voice that actively shapes the camp’s culture.

On our way to more distant Metro sites like Blue Lake and Oxbow regional parks and Quamash Prairie, we play DJ in the van. Each kid who wants to has an opportunity to share their favorite song with the group, and if you know the words, you’d better belt it out. We share food and pass around snacks while some children rest and others catch up with old friends. Many more are deep in conversation forging new friendships.

On our way to more distant Metro sites like Blue Lake and Oxbow regional parks and Quamash Prairie, we play DJ in the van. Each kid who wants to has an opportunity to share their favorite song with the group, and if you know the words, you’d better belt it out. We share food and pass around snacks while some children rest and others catch up with old friends. Many more are deep in conversation forging new friendships.

When we arrive, we remind the kids of what is expected of them. We have no doubts that each and every child will respect the land and respect our leaders. The boundaries are clear, and our expectations for them don’t change when problems arise. We hold them to the highest standards, regardless of their life situation. We respect, listen, and embrace who they are.

We are often greeted by Alice Froehlich, a Metro naturalist. Our kids know Alice, and the mutual trust, respect and accountability we have shared over the last three years has been the foundation to create field trips that cater to the needs of our blended group – and oh, it is a beautiful group.

At Oxbow, we are also greeted by teen leaders from the Oregon Zoo’s ZAP (Zoo Animal Presenters) program. These teens of color join us each year for what always ends up being a highlight of the week: playing in the frigid waters of the Sandy River, our brown skin baking under the hot summer sun, music in the background and so much laughter. Like family, we enjoy one another’s company.

Then we break into smaller groups and head into the ancient forest. Almost immediately the calm of the forest envelopes our youth. The serenity that draws us to nature turns our group of active bodies into quieted beings content to listen, observe, respond and reflect. It doesn’t take much for them to find their rhythm and adjust to nature’s pace. Similarly, when we kayak the Tualatin River or canoe the Columbia Slough, they are keen to show their knowledge of local plants and taking notice as the occasional bird comes into view. We learn as much from them as we do from our guides.

These are the moments that allow Camp ELSO’s participants to feel welcome, not just to fit in but to belong. To feel deeply connected to the earth, to nature and to community.

Encouragement for my community

As a Black environmental educator I’m always navigating two frames of view. One is grounded in my Americanness, the other is grounded in my Blackness, the lineage of my people from where I pull my strength and affirm my birthright. I wear my identities with pride, however difficult it can be to navigate this world as a part of two communities, two identities. One part of me is constantly under attack from the other that is rife with nationalism, anti-Brownness, and opposition toward the people upon whose lives and ancestry this country was built.

As a Black environmental educator I’m always navigating two frames of view. One is grounded in my Americanness, the other is grounded in my Blackness, the lineage of my people from where I pull my strength and affirm my birthright. I wear my identities with pride, however difficult it can be to navigate this world as a part of two communities, two identities. One part of me is constantly under attack from the other that is rife with nationalism, anti-Brownness, and opposition toward the people upon whose lives and ancestry this country was built.

I am a descendant of African people and the motherland. I’m deeply connected to the earth as a descendant of strong, free, resilient and resourceful Black people. The land is a part of me, part of who I am. My ancestors toiled, and they survived, they lived off, they cultivated, and they loved the land.

As a black woman, my relationship with the land and its bounty is a part of my heritage. It’s in my backyard garden, where I grow greens from my great-grandmother’s seeds passed down to me from my mother, who taught me how to save, store and harvest them. Greens from the motherland I was taught to cook by my Sierra Leonean, Rwandese and Jamaican family – aunties and uncles I’ve known as my kin since I was a child. It’s in the birds that roam my backyard, short bursts and squawks as my children chase them. The land is in the final jar my mother canned last summer when the harvest was good, and she had more tomatoes than we could eat after sharing with her church, neighbors and family.

Our connection to the land was lost through colonization, through the blanket of whiteness that a culture and set of values instilled upon us all as westerners living on stolen Indigenous land and working in systems influenced by one dominant culture. Our sacred connection with outdoor spaces was lost as laws set aside the “great outdoors” as if it were for White men only. These laws pushed us from our heritage and erased the stories of our forefathers, forgetting that the Buffalo Soldiers were some of the first park rangers, that the movement for justice was first fought by Black and Brown folks.

We grew our own food before our land was stripped away. We lived in harmony with the natural world before our communities were destroyed, displaced or forcibly relocated. We were healthy and thriving when we ate the food of our ancestors, before it was co-opted and appropriated. We must remember and reclaim this relationship for ourselves and for our children.

We are trying to do this with Camp ELSO, starting with our next generation. Children have the capacity to bring so much to environmental professions that desperately need Black and Brown representation. These professions need the ideas, innovations and solutions that can only come from the lived experiences of people of color. Children of color can solve problems that require Indigenous knowledge, cultural knowledge and knowledge of the African Diaspora. We want to give kids learning experiences that are relevant in today’s context, as more people become aware of racial equity and as the mainstream environmental movement starts to recognize historical oppression of people of color.

We need more spaces for Black and Brown children to see STEM professionals who are relatable through shared experiences, ethnicity, culture and history. We need spaces that allow Black children to experience the outdoors in a majority setting with limited influence of Whiteness – not White people but Whiteness – the dominant culture and norms that influence almost every aspect of our lives.

Camp ELSO is working to be that space. We aren’t there yet. We are on our own learning journey, and it comes with constant challenges and a need to continuously question, heal, build and fortify our own space.

Sprinavasa Brown is the co-founder and executive director of Camp ELSO. She also serves on Metro’s Public Engagement Review Committee and the Parks and Nature Equity Advisory Committee.

Sprinavasa Brown is the co-founder and executive director of Camp ELSO. She also serves on Metro’s Public Engagement Review Committee and the Parks and Nature Equity Advisory Committee.

Advice for White Environmentalists and Nature Educators

by Sprinavasa Brown

I often hear White educators ask “What should I do?” expressing an earnest desire to move beyond talking about equity and inclusion to wanting action steps toward meaningful change.

I will offer you my advice as a fellow educator. It is both a command and a powerful tool for individual and organizational change for those willing to shift their mindset to understand it, invest the time to practice it and hold fast to witness its potential.

The work of this moment is all about environmental justice centered in social justice, led by the communities most impacted by the outcomes of our collective action. It’s time to leverage your platform as a White person to make space for the voice of a person of color. It’s time to connect your resources and wealth to leaders from underrepresented communities so they can make decisions that place their community’s needs first.

If you have participated in any diversity trainings, you are likely familiar with the common process of establishing group agreements. Early on, set the foundation for how you engage colleagues, a circumspect reminder that meaningful interpersonal and intrapersonal discourse has protocols in order to be effective. I appreciate these agreements and the principles they represent because they remind us that this work is not easy. If you are doing it right, you will and should be uncomfortable, challenged and ready to work toward a transformational process that ends in visible change.

I want you to recall one such agreement: step up, step back, step aside.

That last part is where I want to focus. It’s a radical call to action: Step aside! There are leaders of color full of potential and solutions who no doubt hold crucial advice and wisdom that organizations are missing. Think about the ways you can step back and step aside to share power. Step back from a decision, step down from a position or simply step aside. If you currently work for or serve on the board of an organization whose primary stakeholders are from communities of color, then this advice is especially for you.

Stepping aside draws to attention arguably the most important and effective way White people can advance racial equity, especially when working in institutions that serve marginalized communities. To leverage your privilege for marginalized communities means removing yourself from your position and making space for Black and Brown leaders to leave the margins and be brought into the fold of power.

You may find yourself with the opportunity to retire or take another job. Before you depart, commit to making strides to position your organization to hire a person of color to fill the vacancy. Be outspoken, agitate and question the status quo. This requires advocating for equitable hiring policies, addressing bias in the interview process and diversifying the pool with applicants with transferable skills. Recruit applicants from a pipeline supported and led by culturally specific organizations with ties to the communities you want to attract, and perhaps invite those community members to serve on interview panels with direct access to hiring managers.

As an organizational leader responsible for decisions related to hiring, partnerships and board recruitment, I have made uncomfortable, hard choices in the name of racial equity, but these choices yield fruitful outcomes for leaders willing to stay the course. I’ve found myself at crossroads where the best course forward wasn’t always clear. This I have come to accept is part of my equity journey. Be encouraged: Effective change can be made through staying engaged in your personal equity journey. Across our region we have much work ahead at the institutional level, and even more courage is required for hard work at the interpersonal level.

In stepping aside you create an opportunity for a member of a marginalized community who may be your colleague, fellow board member or staff member to access power that you have held.

White people alone will not provide all of the solutions to fix institutional systems of oppression and to shift organizational culture from exclusion to inclusion. These solutions must come from those whose voices have not been heard. Your participation is integral to evolving systems and organizations and carrying out change, but your leadership as a White person in the change process is not.

The best investment we can make for marginalized communities is to actively create and hold space for leaders of color at every level from executives to interns. Invest time and energy into continuous self-reflection and selfevaluation. This is not the path for everyone, but I hope you can see that there are a variety of actions that can shift the paradigm of the environmental movement. If you find yourself unsure of what action steps best align with where you or your organization are at on your equity journey, then reach out to organizations led by people of color, consultants, and leaders and hire them for their leadership and expertise. By placing yourself in the passenger seat, with a person of color as the driver, you can identify areas to leverage your privilege to benefit marginalized communities.

Finally, share an act of gratitude. Be cognizant of opportunities to step back and step aside and actively pursue ways to listen, understand and practice empathy with your colleagues, community members, neighbors and friends.

Camp ELSO is an example of the outcomes of this advice. Our achievements are most notable because it is within the context of an organization led 100 percent by people of color from our Board of Directors to our seasonal staff. This in the context of a city and state with a history of racial oppression and in a field that is historically exclusively White.

We began as a community-supported project and are growing into a thriving community-based organization successfully providing a vital service for Black and Brown youths across the Portland metro area. The support we have received has crossed cultures, bridged the racial divide and united partners around our vision. It is built from the financial investments of allies – public agencies, foundations, corporations and individuals. I see this as an act of solidarity with our work and our mission, and more importantly, an act of solidarity and support for our unwavering commitment to racial equity.

by editor | Dec 1, 2019 | K-12 Activities

K-12 Activity Ideas:

Monitoring Biological Diversity

by Roxine Hameister

Developing a biodiversity monitoring project at your school can help students develop many skills in an integrated manner. Here are some simple ideas that you can use to get your students started.

Children and teachers are being pulled in many directions. Children want to “learn by doing/’ but because of societal fears for children’s safety, they are very often not allowed to play outdoors and learn at will. Teachers are encouraged to meet the unique learning styles of all students but the classroom reality often means books and pictures rather than hands-on experiences. In addition, children are under considerable pressure to be thinking about their futures and what further, post secondary, education they might be considering.

Sometimes children just like science. Many are of the “naturalist intelligence” and enjoy learning how to classify their world. Activities that meet all these requirements are within schools’ meagre budgets and are indeed possible. These projects are equally possible for the teacher with little science or biology background knowledge. The science skills are readily picked up; being systematic about collecting and recording the data is the main skill needed. The curriculum integration that is possible from these projects range from field studies to computer skills, to art and literature; the entire curriculum is covered in these activities. (more…)

by editor | Sep 27, 2019 | Equity and Inclusion, Outdoor education and Outdoor School, Teaching Science

by Sprinavasa Brown

I often hear White educators ask “What should I do?” expressing an earnest desire to move beyond talking about equity and inclusion to wanting action steps toward meaningful change.

I will offer you my advice as a fellow educator. It is both a command and a powerful tool for individual and organizational change for those willing to shift their mindset to understand it, invest the time to practice it and hold fast to witness its potential.

The work of this moment is all about environmental justice centered in social justice, led by the communities most impacted by the outcomes of our collective action. It’s time to leverage your platform as a White person to make space for the voice of a person of color. It’s time to connect your resources and wealth to leaders from underrepresented communities so they can make decisions that place their community’s needs first.

If you have participated in any diversity trainings, you are likely familiar with the common process of establishing group agreements. Early on, set the foundation for how you engage colleagues, a circumspect reminder that meaningful interpersonal and intrapersonal discourse has protocols in order to be effective. I appreciate these agreements and the principles they represent because they remind us that this work is not easy. If you are doing it right, you will and should be uncomfortable, challenged and ready to work toward a transformational process that ends in visible change.

I want you to recall one such agreement: step up, step back, step aside.

That last part is where I want to focus. It’s a radical call to action: Step aside! There are leaders of color full of potential and solutions who no doubt hold crucial advice and wisdom that organizations are missing. Think about the ways you can step back and step aside to share power. Step back from a decision, step down from a position or simply step aside. If you currently work for or serve on the board of an organization whose primary stakeholders are from communities of color, then this advice is especially for you.

Stepping aside draws to attention arguably the most important and effective way White people can advance racial equity, especially when working in institutions that serve marginalized communities. To leverage your privilege for marginalized communities means removing yourself from your position and making space for Black and Brown leaders to leave the margins and be brought into the fold of power.

You may find yourself with the opportunity to retire or take another job. Before you depart, commit to making strides to position your organization to hire a person of color to fill the vacancy. Be outspoken, agitate and question the status quo. This requires advocating for equitable hiring policies, addressing bias in the interview process and diversifying the pool with applicants with transferable skills. Recruit applicants from a pipeline supported and led by culturally specific organizations with ties to the communities you want to attract, and perhaps invite those community members to serve on interview panels with direct access to hiring managers.

As an organizational leader responsible for decisions related to hiring, partnerships and board recruitment, I have made uncomfortable, hard choices in the name of racial equity, but these choices yield fruitful outcomes for leaders willing to stay the course. I’ve found myself at crossroads where the best course forward wasn’t always clear. This I have come to accept is part of my equity journey. Be encouraged: Effective change can be made through staying engaged in your personal equity journey. Across our region we have much work ahead at the institutional level, and even more courage is required for hard work at the interpersonal level.

In stepping aside you create an opportunity for a member of a marginalized community who may be your colleague, fellow board member or staff member to access power that you have held.

White people alone will not provide all of the solutions to fix institutional systems of oppression and to shift organizational culture from exclusion to inclusion. These solutions must come from those whose voices have not been heard. Your participation is integral to evolving systems and organizations and carrying out change, but your leadership as a White person in the change process is not.

The best investment we can make for marginalized communities is to actively create and hold space for leaders of color at every level from executives to interns. Invest time and energy into continuous self-reflection and selfevaluation. This is not the path for everyone, but I hope you can see that there are a variety of actions that can shift the paradigm of the environmental movement. If you find yourself unsure of what action steps best align with where you or your organization are at on your equity journey, then reach out to organizations led by people of color, consultants, and leaders and hire them for their leadership and expertise. By placing yourself in the passenger seat, with a person of color as the driver, you can identify areas to leverage your privilege to benefit marginalized communities.

Finally, share an act of gratitude. Be cognizant of opportunities to step back and step aside and actively pursue ways to listen, understand and practice empathy with your colleagues, community members, neighbors and friends.

Camp ELSO is an example of the outcomes of this advice. Our achievements are most notable because it is within the context of an organization led 100 percent by people of color from our Board of Directors to our seasonal staff. This in the context of a city and state with a history of racial oppression and in a field that is historically exclusively White.

We began as a community-supported project and are growing into a thriving community-based organization successfully providing a vital service for Black and Brown youths across the Portland metro area. The support we have received has crossed cultures, bridged the racial divide and united partners around our vision. It is built from the financial investments of allies – public agencies, foundations, corporations and individuals. I see this as an act of solidarity with our work and our mission, and more importantly, an act of solidarity and support for our unwavering commitment to racial equity.

Sprinavasa Brown is the co-founder and executive director of Camp ELSO. She also serves on Metro’s Public Engagement Review Committee and the Parks and Nature Equity Advisory Committee.

by editor | Mar 19, 2018 | Outdoor education and Outdoor School, STEM

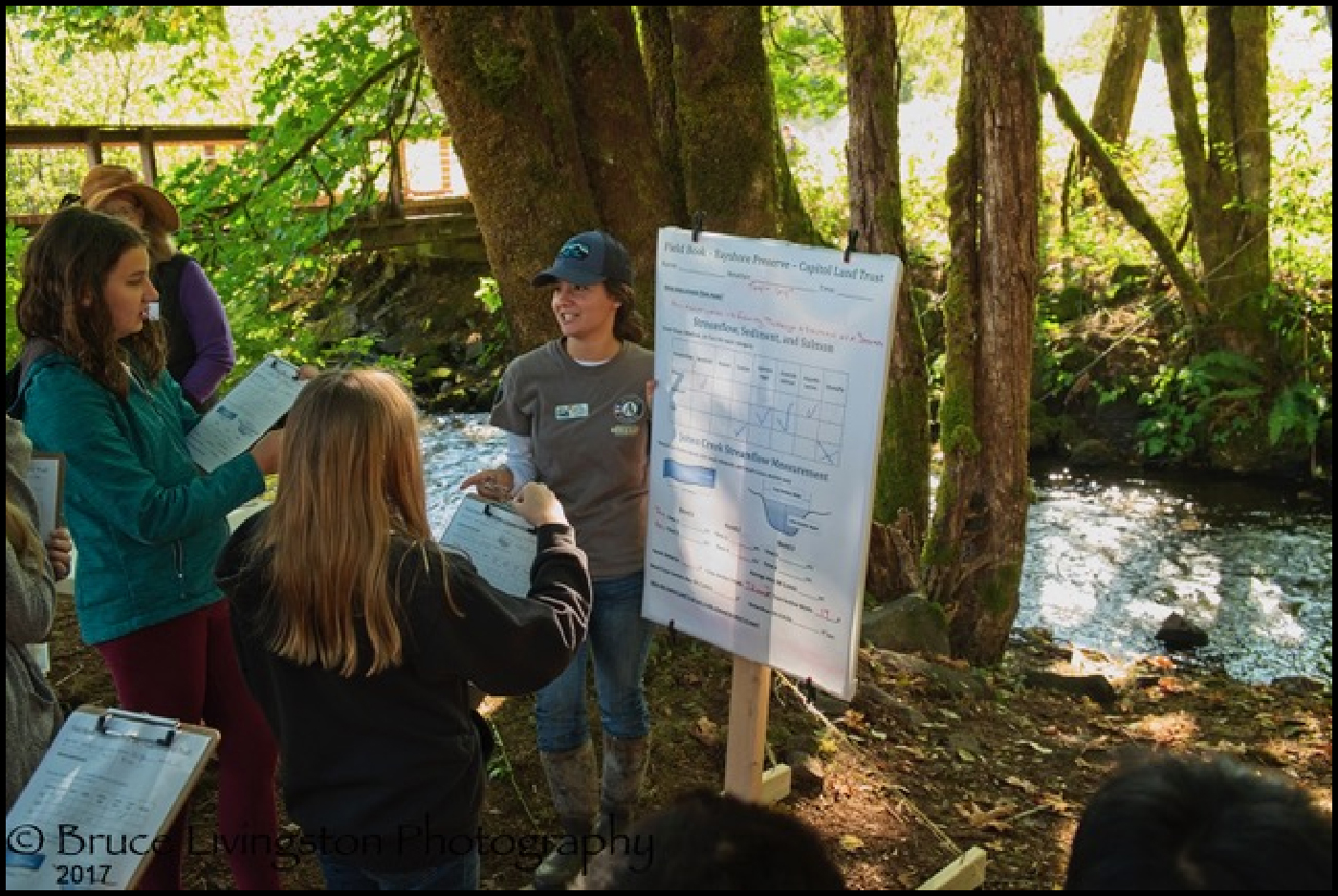

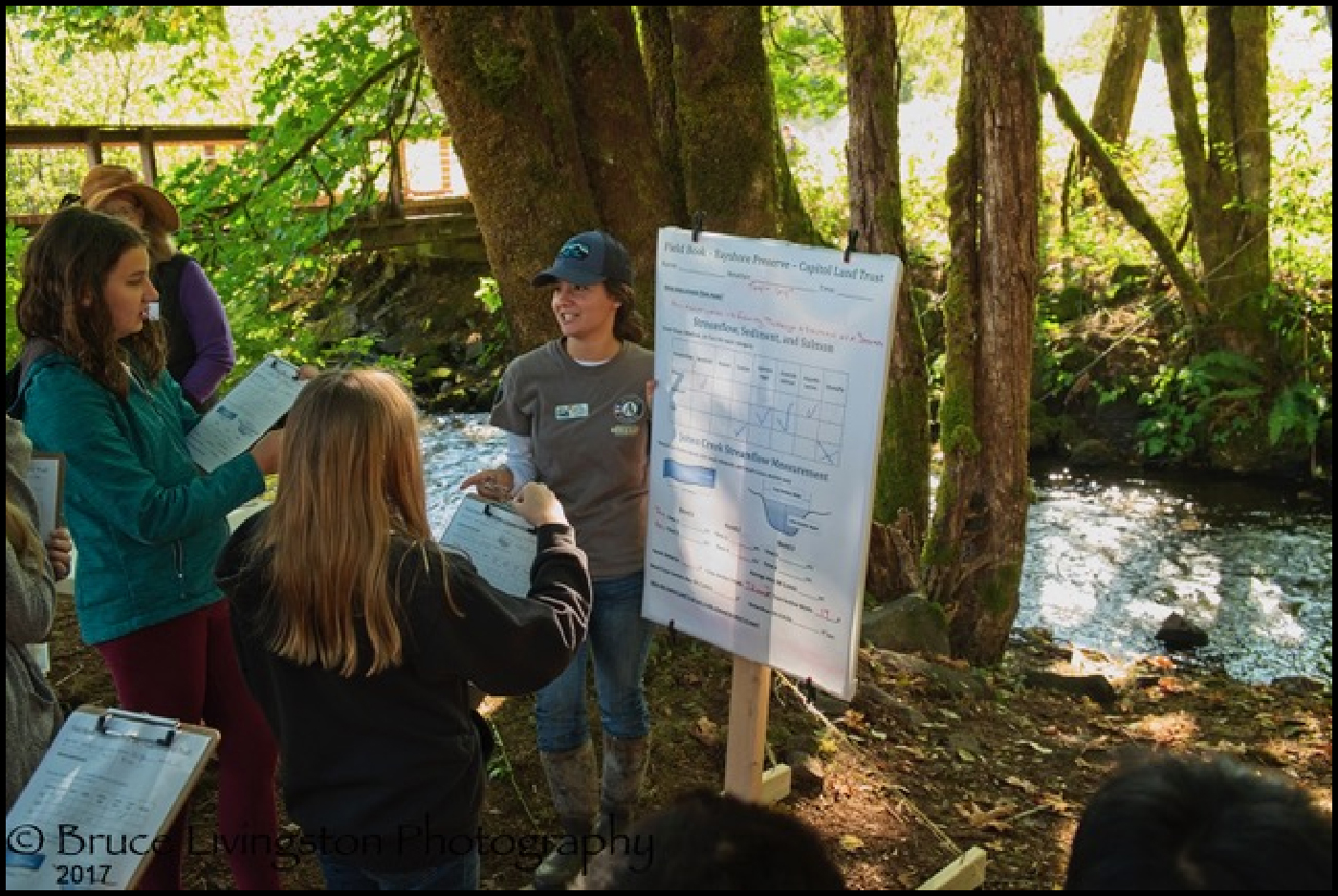

Mary Birchem, Restoration Coordinator with Capitol Land Trust, guides students through a discussion of streamflow next to Johns Creek on the Bayshore Preserve. Photo by Bruce Livingston.

Outdoor Learning in Shelton: A Surge of Hope

by Eleanor Steinhagen

Bayshore Preserve – Shelton, WA

wo 7th graders have just tossed their pears into Johns Creek and are jogging downstream to see which one will cross the finish line first. Maneuvering around a large maple tree and jagged rocks on the stream’s bank, a handful of their classmates jog with them, including two “timers” who hold stopwatches in front of their chests, ready to hit the stop button when their designated pear reaches the finish line. The pears bob up and down for a moment, then drift into the creek’s swiftly flowing current and float eastward toward Oakland Bay.

wo 7th graders have just tossed their pears into Johns Creek and are jogging downstream to see which one will cross the finish line first. Maneuvering around a large maple tree and jagged rocks on the stream’s bank, a handful of their classmates jog with them, including two “timers” who hold stopwatches in front of their chests, ready to hit the stop button when their designated pear reaches the finish line. The pears bob up and down for a moment, then drift into the creek’s swiftly flowing current and float eastward toward Oakland Bay.

The rest of the students are already standing at the finish line, peering upstream and cheering on their desired winner as they hunch forward and hide their hands in their sleeves to protect them from the frigid October morning air. It’s a sunny morning, but the temperature hovers in the high 30s and is slow to rise in the shade by the creek. As the winning pear crosses the finish line 25 seconds after the start of the race, several kids break into a loud cheer, while others throw their hands in the air, or turn away and yell, “Aw, man!” in disappointment.

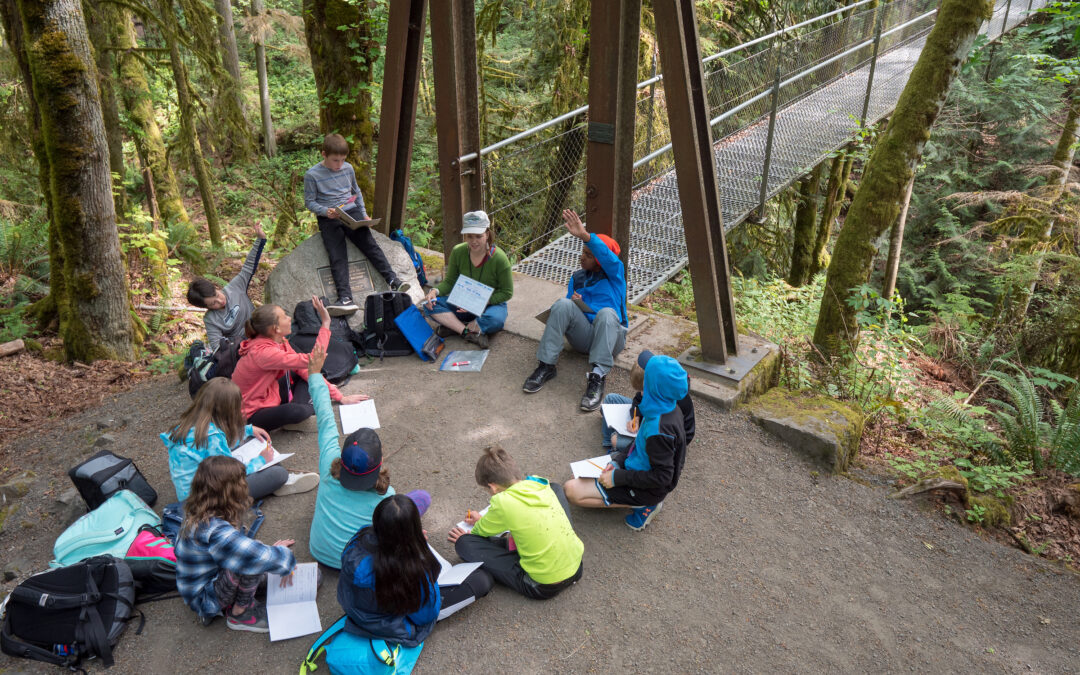

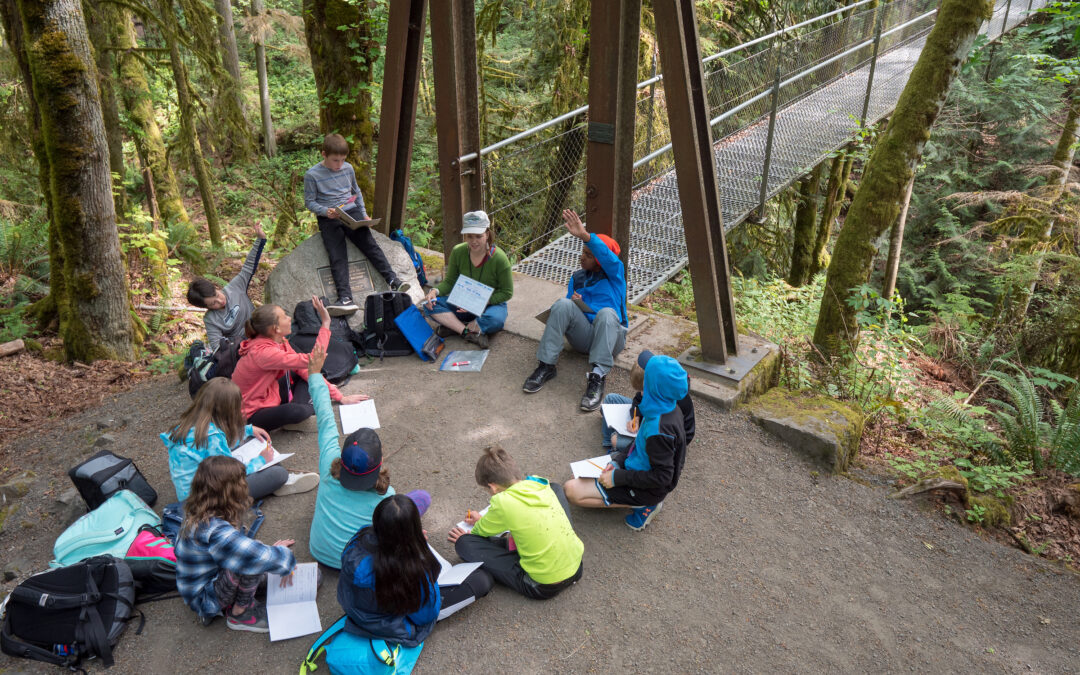

The race was one of three that this group of 13 students conducted as a means of collecting the data they needed to measure streamflow in the creek at Bayshore Preserve, a 74-acre former golf course three miles northwest of Shelton, Washington, conserved by Capitol Land Trust in 2014. Before the race, the students learned about side channels and discussed how they impact flow; measured the distance from the race’s starting line to the finish line, or the “reach”; discussed key concepts they are learning in class, such as “ecosystem” and “biodiversity”; and, standing mere feet from the creek’s sand, cobble and stoneflies, they learned about the variety of sediments and creatures in northwest streams and where each can be found according to streamflow. Throughout the lesson, they used field journals to take notes and record data, including the depth and width of the section of the creek they were studying—information they would use to perform calculations in math class later that week.

The students’ work at Johns Creek is the culmination of three years of effort made by several groups to design and implement high impact field experiences for every student in the Shelton School District. The program started with a conversation at a community stakeholder meeting in 2014 between Margaret Tudor, then-Executive Director of Pacific Education Institute (PEI), Wendy Boles, Shelton School District Science Curriculum Leader and Science Teacher at Olympic Middle School, and Amanda Reed, Executive Director of Capitol Land Trust. Since the fall of 2015, Capitol Land Trust has been facilitating these field investigations for every 7th grader in the Shelton School District—serving around 300 students per year—using PEI’s trademark FieldSTEM model as a foundation for the work. In addition to Capitol Land Trust, Shelton School District and PEI, a handful of dedicated volunteers and other community stakeholders, such as the Squaxin Island Tribe, Mason County Conservation District, Green Diamond Resources and Taylor Shellfish, have stepped forward to support the program.

A student draws an example of a freshwater macroinvertebrate for his classmates to add to their field journals. Opportunities for students to share their work and learn from one another are built into the field investigation curriculum. Photo by Bruce Livingston.

This type of outdoor hands-on STEM learning appeals to many learner types and helps students overcome barriers to learning often found inside the classroom. During this first field investigation day, a group of students was asked why they liked learning science outside. Rian, a student at Olympic Middle School who used to go clamming near Bayshore with his mom and grandparents, said, ”I know some kids, they’re better with a complete visual. Not like a visual coming from a book, or written on a whiteboard.” Another student, Madison, said, “It’s good to be outside because you get physical education and you get to look at a lot of stuff,” she said. “I like coming out here to do hands-on learning and have fun with my friends.”

Capitol Land Trust in particular has done a lot of work to realize the initial vision of using Bayshore as a place to provide Shelton School District students with these learning opportunities. Daron Williams, Community Conservation Manager, and Mary Birchem, AmeriCorps Restoration Coordinator, are the land trust’s “boots on the ground,” making the improvements needed each year to transform the program from an average field trip to a PEI-style high impact field experience. Of his drive to help make these experiences happen for students, Daron said:

Doing FieldSTEM—where [students] can get the knowledge they need in a way that actually works for them—can help connect them with the land they live on. Shelton is an economically impoverished area. And a lot of families are struggling… As a small organization, we bring a capacity that the schools don’t have on their own. And that can make a difference in the students’ lives. Doing these project-based lessons, we could actually be helping students get through school that maybe wouldn’t have, and get them excited about science. This is a way to show them how science is connected to the real world.

To this end, Daron and Mary have worked tirelessly to increase student engagement and develop the program curriculum. When the program started in 2015, Daron collaborated with teachers to correlate what Bayshore offers and what is taught in the field to what students are learning in the classroom, ensuring that the lessons are aligned with state and national learning standards. In the summer of 2017, a year into her AmeriCorps service with Capitol Land Trust, Mary began recruiting additional volunteer teachers, and then designed and implemented a program to train them. Together, they have worked to adjust the schedule and coordinate the logistics of the field experience with district teachers. And on field experience days, both Mary and Daron work alongside the volunteer teachers to help them guide students through the FieldSTEM tasks.

This year especially, their effort shows. Viola Moran, student teacher at Olympic Middle School, shared her observation of Fiona (her name has been changed to protect her privacy) during the field investigation at Bayshore. A high-needs student in one of the district middle schools, Fiona doesn’t like to be the center of attention. As a rule, she doesn’t participate in activities or raise her hand in class. The commotion that comes with being in large groups of people makes her feel so uncomfortable that she waits in the bathroom until the hallways clear out during breaks before going to class. And when she gets there, she doesn’t want to sit with the other students.

When the Bayshore field investigation day was announced, Fiona said, “I’m not going. I’ll be sick that day.” But in spite of her reluctance, she got her permission slip in and ended up attending. And in the course of the afternoon, she became so engaged in the fieldwork that she and her classmates were doing that she volunteered to throw one of the pears during the fruit race. She also offered to draw an example of a macroinvertebrate on the board for the class—a profound shift from what Viola had observed in the classroom.

Throughout the first field investigation day, as well as the week following, Wendy, Viola, Mary, Daron and several of the volunteer teachers remarked that student engagement is at an all-time high this year. With the inevitable exceptions of “kids being kids,” the students listened attentively, asked questions, volunteered for a variety of tasks and diligently took notes and recorded their data. Viola and Wendy also observed that the students handled the creatures more gently this year than in the past. At the “Tidal Life” station, for example, on the first day of the field investigation, a group of students were so concerned about a hermit crab that had shed its shell in the molting process that they spent 10 minutes trying to persuade the crab to crawl into a shell they had found on the shore while offering various words of encouragement: “You want your shell!” and “Come on, man, you need a home!”

Students examine macroinvertebrates at the saltwater station. For many of them, this is the first time they’ve come into contact with the creatures that live in their surrounding area. Photo by Bruce Livingston.

Viola expounded on the above by adding:

Even though this is their community, there’s a good portion of [the students] that have never actually been around the creatures out there. And so, seeing the hermit crabs and the different specimens that they got to handle—they were just fascinated by that… And as they grow up, it’s right there. It’s a part of their environment.

What’s more, the impact of the field experience was evident in the classroom after the students went to Bayshore. “When we are going over ‘producer, consumer and decomposer,’” Viola said, “they are relating back to the information they got at Bayshore.”

Susie Vanderburg, retired elementary school teacher, former Thurston County Stream Team Coordinator and former Education Director for Olympia’s LOTT WET Science Center, agrees with Viola. “A lot of kids today are not getting exposed to the outdoors, not having experiences outside. They’re not given opportunities to love the land and be fascinated.” While her work as a volunteer is a big commitment, Susie does it because she believes that giving kids the opportunity to learn science outside, in the field, simultaneously gives them the opportunity to become stewards of the land they live on. “In environmental education we always say, once you get to know something, like a wetland or a prairie, then you begin to care about it. It’s personal. And if you care about it, then you’re willing to do something to protect it. If you never get outside and get to know the outdoors, you’re never going to care about it, you’re not going to protect it.”

While young people’s lack of exposure to the natural world poses a challenge, Wendy Boles, who is in her 15th year as a science teacher and is another major force behind implementing these powerful experiences for students, has begun to feel a surge of hope with a discovery she’s made in her classroom in recent years. It used to be that students entered her 7th grade class without any knowledge about (and very little interest in) the problems caused by issues such as overpopulation, resource depletion and pollution. In the past few years, however, Wendy has noticed in her students an increased awareness of and concern about climate change and environmental issues. She sees field investigations as an opportunity to help kids make the connection between these issues and how they impact their community. She hopes that by having real-world science learning experiences, her students will discover what they love to do, learn about science-related careers in their communities and be empowered to pursue them if that’s their dream.

Along with the work she does to help integrate the field investigation tasks with the district’s science curriculum, Wendy helps train volunteers and coordinate schedules with Capitol Land Trust, district teachers and the English language support staff that the district provides. “It is a lot of work. I mean a lot of work,” she said of the field investigation days. But all of that becomes worth it when she witnesses the new awareness among her students and their desire to safeguard the environment. “The kids are starting to go, Wow, we have to start caring about the environment. That to me is the biggest thing because if we aren’t taking measures to be good stewards, we are going to be in trouble. That’s my concern. Making sure that our planet can continue to support us in a way that we’re used to.”

At Bayshore, several individuals and community partners have come together to seize this opportunity by providing Wendy’s students, and every 6th and 7th grade student in the Shelton School District, with real-world, project-based, career-connected science education. The hope is that this education will enable them to lead richer and more meaningful lives, and that they, in turn, will draw from their time exploring and learning science out in their community to generate change where they can. Yes, it is a lot of work. Everyone involved agrees with Wendy on that. But they do it because they believe that the return will be well worth the effort.

Eleanor Steinhagen is the Communications Coordinator for Pacific Education Institute in Olympia, Washington.

s an outdoor educator, I often get sucked into the false binary that lessons are either fun or informative, that content must be sweetened with games, stories, and activities like applesauce for children’s medicine. But stories are one of the oldest forms of teaching known to humankind, and games and interactive activities help students interpret and internalize what they learn on trails, in classrooms, and at home. In this article, I invite you to stop apologizing for your content teaching and start weaving it into lesson sequences that include stories, games, writing activities, and more. Sequences can make your teaching practices more effective, more equitable, and yes, more fun.

s an outdoor educator, I often get sucked into the false binary that lessons are either fun or informative, that content must be sweetened with games, stories, and activities like applesauce for children’s medicine. But stories are one of the oldest forms of teaching known to humankind, and games and interactive activities help students interpret and internalize what they learn on trails, in classrooms, and at home. In this article, I invite you to stop apologizing for your content teaching and start weaving it into lesson sequences that include stories, games, writing activities, and more. Sequences can make your teaching practices more effective, more equitable, and yes, more fun.

We are creating a special place for Black and Brown youth to have transformative experiences, to create memories that we hope will stick with them until adulthood. Creating such a space comes with difficulties, the type of challenges that force our leadership to make tough decisions that we believe will yield the best outcomes for youth underrepresented in STEM fields. For instance, how to mitigate the undertones of colonization, nationalism, and co-opting of traditional knowledge – harmful practices ingrained in mainstream environmental education.

We are creating a special place for Black and Brown youth to have transformative experiences, to create memories that we hope will stick with them until adulthood. Creating such a space comes with difficulties, the type of challenges that force our leadership to make tough decisions that we believe will yield the best outcomes for youth underrepresented in STEM fields. For instance, how to mitigate the undertones of colonization, nationalism, and co-opting of traditional knowledge – harmful practices ingrained in mainstream environmental education. On our way to more distant Metro sites like Blue Lake and Oxbow regional parks and Quamash Prairie, we play DJ in the van. Each kid who wants to has an opportunity to share their favorite song with the group, and if you know the words, you’d better belt it out. We share food and pass around snacks while some children rest and others catch up with old friends. Many more are deep in conversation forging new friendships.

On our way to more distant Metro sites like Blue Lake and Oxbow regional parks and Quamash Prairie, we play DJ in the van. Each kid who wants to has an opportunity to share their favorite song with the group, and if you know the words, you’d better belt it out. We share food and pass around snacks while some children rest and others catch up with old friends. Many more are deep in conversation forging new friendships. As a Black environmental educator I’m always navigating two frames of view. One is grounded in my Americanness, the other is grounded in my Blackness, the lineage of my people from where I pull my strength and affirm my birthright. I wear my identities with pride, however difficult it can be to navigate this world as a part of two communities, two identities. One part of me is constantly under attack from the other that is rife with nationalism, anti-Brownness, and opposition toward the people upon whose lives and ancestry this country was built.

As a Black environmental educator I’m always navigating two frames of view. One is grounded in my Americanness, the other is grounded in my Blackness, the lineage of my people from where I pull my strength and affirm my birthright. I wear my identities with pride, however difficult it can be to navigate this world as a part of two communities, two identities. One part of me is constantly under attack from the other that is rife with nationalism, anti-Brownness, and opposition toward the people upon whose lives and ancestry this country was built. Sprinavasa Brown is the co-founder and executive director of Camp ELSO. She also serves on Metro’s Public Engagement Review Committee and the Parks and Nature Equity Advisory Committee.

Sprinavasa Brown is the co-founder and executive director of Camp ELSO. She also serves on Metro’s Public Engagement Review Committee and the Parks and Nature Equity Advisory Committee.