by editor | Sep 20, 2025 | Data Collection, Environmental Literacy, Experiential Learning, Forest Education, Inquiry, Integrating EE in the Curriculum, Learning Theory, Marine/Aquatic Education, Questioning strategies

Building a Community: The Value of a Diack Teacher Workshop

Teachers are being asked to do more than ever before. We are inundated with meetings, grading, analyzing data and curriculum development. The idea of taking kids outside to do field-based research can be daunting and filled with bureaucratic hurdles. Given all this, why should we take our precious time to implement this new type of learning?

by Tina Allahverdian

It is a warm summer day at Silver Falls State Park and a group of teachers are conducting a macroinvertebrate study on the abundance and richness of species around the swimming hole. The air is filled with sounds of laughter from children playing, parents conversing on the bank, and the gentle babble of the stream below the dam. The teachers, armed with Dnets, clipboards, and other sampling equipment, move purposefully through the water collecting aquatic species. Being a leader at this unique workshop, I am there to support the teacher’s inquiry project and also help brainstorm ways to bring this type of work back to their classrooms.

It is a warm summer day at Silver Falls State Park and a group of teachers are conducting a macroinvertebrate study on the abundance and richness of species around the swimming hole. The air is filled with sounds of laughter from children playing, parents conversing on the bank, and the gentle babble of the stream below the dam. The teachers, armed with Dnets, clipboards, and other sampling equipment, move purposefully through the water collecting aquatic species. Being a leader at this unique workshop, I am there to support the teacher’s inquiry project and also help brainstorm ways to bring this type of work back to their classrooms.

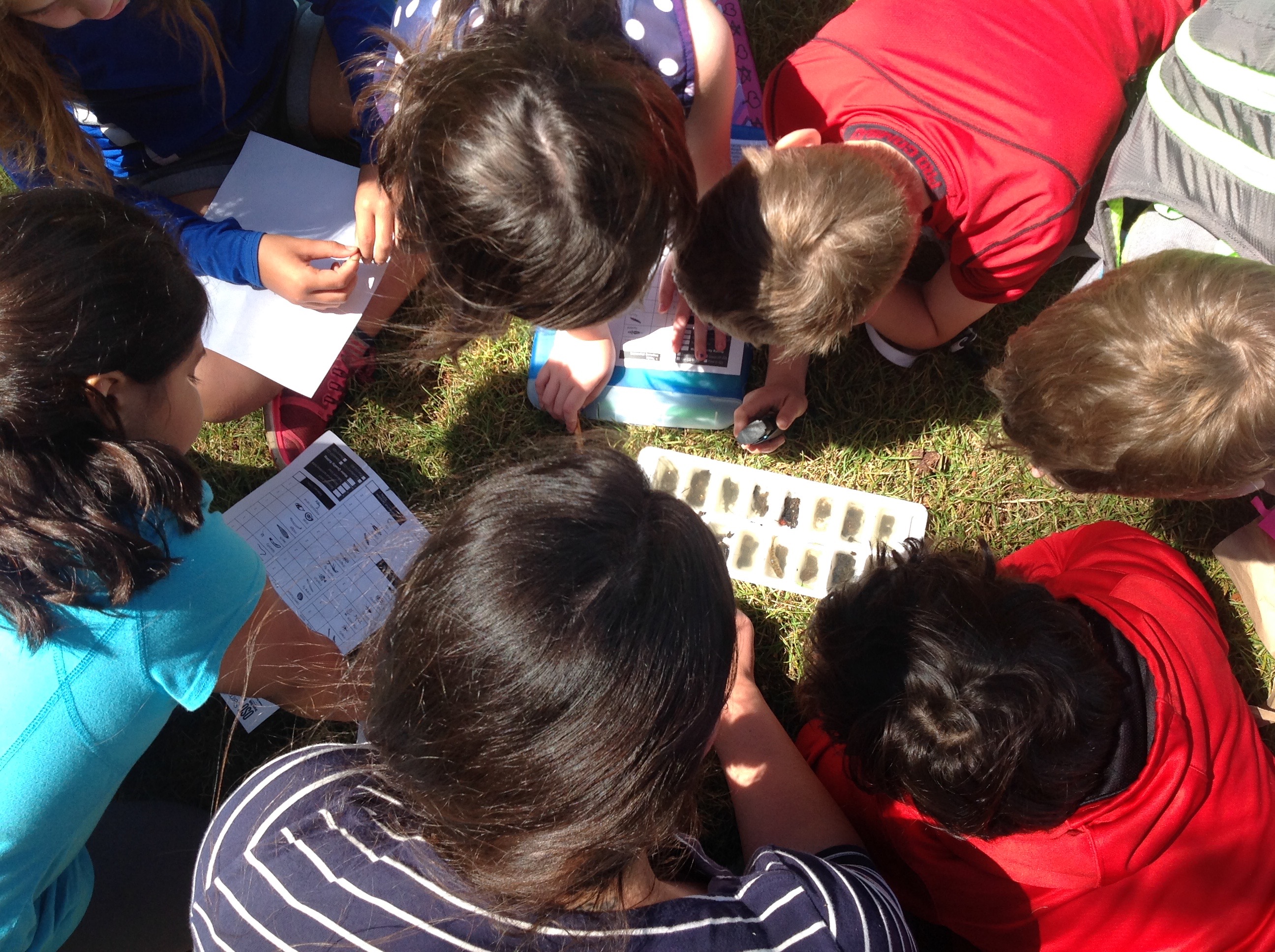

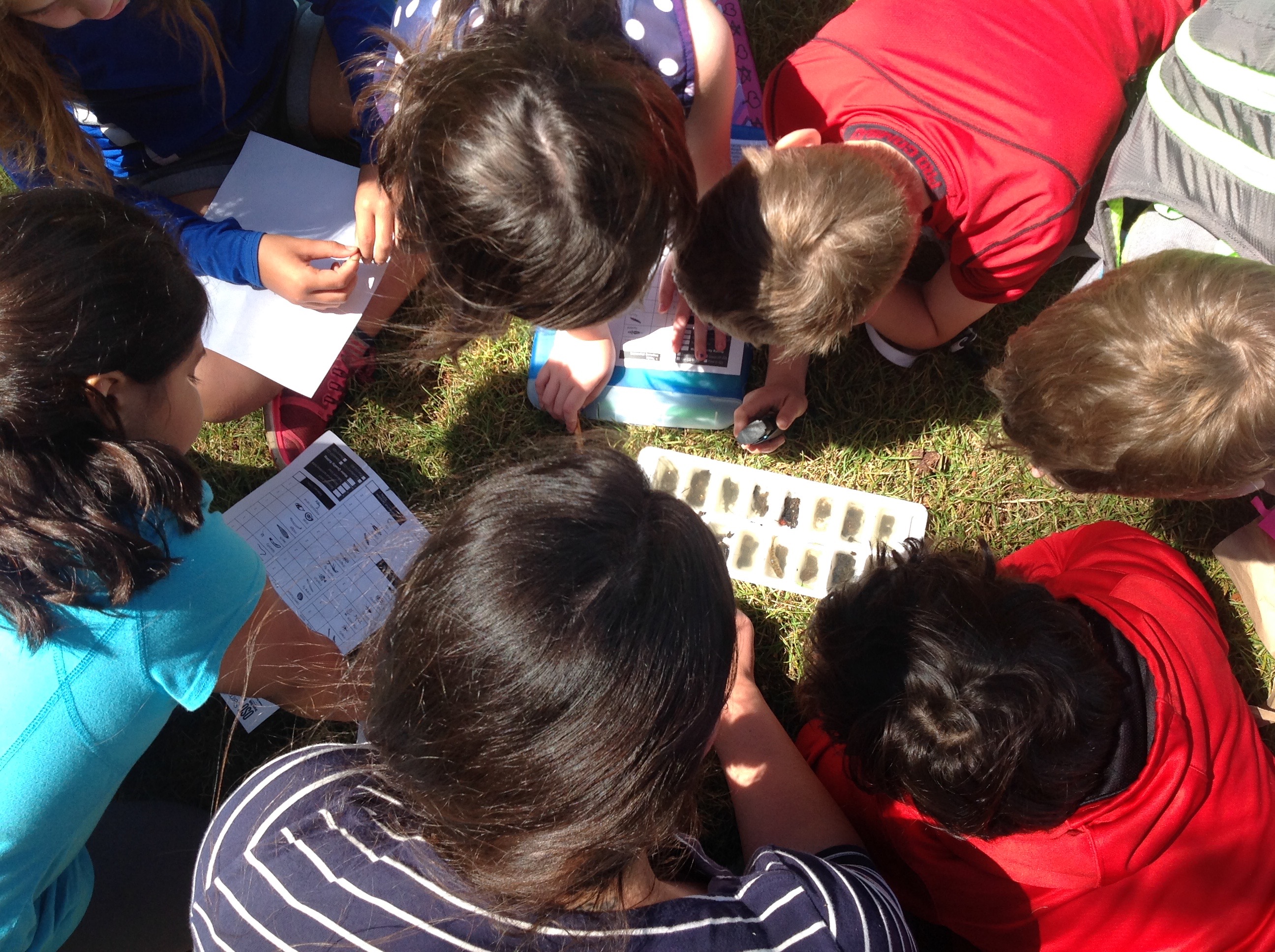

The buckets on the bank soon host a variety of species like water beetles, caddisflies, and stonefly nymphs, offering a snapshot of the rich biodiversity in the stream. We teachers sit on the bank, peering into the tubs, magnifying lenses and field guides in hand. We fill out data collection forms and discuss our findings. On this particular summer day, several young children at the park gather to see what we are doing. Their curiosity is piqued by the idea of discovering the hidden inhabitants of the aquatic ecosystem they are swimming in. The teachers and I patiently explain the project to the children and their parents. While some of the crowd goes back to swimming, two little girls stay for over an hour to help identify species. Later, while we pack up a mother stops to thank us for including her daughter in the scientific process. She shares that discovering the magic of the stream with us is her daughter’s idea of a perfect day. This moment is a testament to the power of experiential learning and the unexpected magic that can happen when we take learning into the field.

After the field work is completed, we all gather back at the lodge to create posters and present our results to the rest of the workshop participants. Based on individual interests and grade levels, teachers work in small groups to analyze their data and share their conclusions and questions. There are various topics that groups are curious about — from lichen or moss, to bird behavior and effects of a recent fire on the tree species. Teachers take on the work of scientists so they can get a feel for the experience their students will have in the future.

Teachers often want to backwards plan, knowing the end product their students will experience and learn. But this type of scientific inquiry requires us to let go of control so that students can ask authentic, meaningful questions that are not yet answered. Teachers come to learn that teaching the process of science is often more valuable than teaching the content. They are engaging in the work of true scientists and learning how to be curious, lifelong learners along the way. Being a part of inspiring projects and trips such as these is an experience that teachers, students, and even parent volunteers will remember for years to come. As an upper elementary teacher myself, I often hear about the power of our work when families come back to visit and reminisce about their time in my classroom. I know that this work will impact future generations and their enthusiasm for science learning. Not only that, we are teaching students to do, read and understand the work of a scientist so they can make informed choices in their adult lives.

Teachers often want to backwards plan, knowing the end product their students will experience and learn. But this type of scientific inquiry requires us to let go of control so that students can ask authentic, meaningful questions that are not yet answered. Teachers come to learn that teaching the process of science is often more valuable than teaching the content. They are engaging in the work of true scientists and learning how to be curious, lifelong learners along the way. Being a part of inspiring projects and trips such as these is an experience that teachers, students, and even parent volunteers will remember for years to come. As an upper elementary teacher myself, I often hear about the power of our work when families come back to visit and reminisce about their time in my classroom. I know that this work will impact future generations and their enthusiasm for science learning. Not only that, we are teaching students to do, read and understand the work of a scientist so they can make informed choices in their adult lives.

Every time I help lead this workshop, I witness a transformation among the participants over the course of the three days. On the last day we give a feedback form which is always filled with so much enthusiasm for taking the learning back to the classroom and to colleagues; I often hear this is the best professional development they have experienced in a long time because it is so practical and hands-on. One of my favorite parts about the Diack field science workshops is witnessing the teacher’s excitement for learning about nature that I know will be passed on to students back in the classroom. Twice a year we meet at a beautiful location in Oregon where teachers from many different districts have the opportunity to carry out the mini-inquiry project and plan curriculum that promotes student-driven, field based science inquiry for K-12 students.

Perhaps one of the most significant outcomes of the Diack Ecology Workshop is the formation of a community of educators passionate about outdoor learning. Teachers exchange ideas, share success stories, and collaborate on developing resources for implementing field-based inquiry projects. They share ideas across grade levels to get a sense of where their students are going and have come from. This sense of community not only strengthens the impact of the program but also creates a support network for educators venturing into the world of environmental education. I always leave the workshop inspired by the creativity, collaboration, and joy from teachers. It is one of my favorite parts of the summer and I would encourage anyone who works with students to come join us and experience the magic.

Tina Allahverdian is passionate about connecting students with science in the natural world. When not teaching fifth graders, she can be found reading in a hammock, kayaking through Pacific Northwest waters, or hiking in the mountains. She currently teaches in West Linn, Oregon, and resides in SE Portland with her husband, twin boys, and their dog, Nalu.

Tina Allahverdian is passionate about connecting students with science in the natural world. When not teaching fifth graders, she can be found reading in a hammock, kayaking through Pacific Northwest waters, or hiking in the mountains. She currently teaches in West Linn, Oregon, and resides in SE Portland with her husband, twin boys, and their dog, Nalu.

by editor | Sep 15, 2025 | Conservation & Sustainability, Data Collection, Experiential Learning, Inquiry, Integrating EE in the Curriculum, Schoolyard Classroom, Student research, Teaching Science

Scotch Broom Saga:

Restoring a School Habitat as Project-Based Learning and Inquiry

by Edward Nichols and Christina Geierman

Since the advent of No Child Left Behind, many schools have turned their focus inward. Students rarely leave the classroom. Teachers often deliver purchased curricula that attempt to make meaningful connections for students. Lessons may contain examples from the real world, but these exist only on paper and are not explored within a real-world context. This article describes how an elementary school (K-5) on the southern Oregon coast addressed a real-world problem– the presence of the invasive Scotch broom (Cytisus scoparius) plant on the school campus. It began as a plan to improve an outdated writing work sample but became a school-wide project that allowed ample opportunities for students to authentically practice research skills while developing a sense of value for the world around them.

North Bay Elementary School is located in the temperate rainforest of rural Oregon, just a few miles from the Pacific Ocean. It serves about 430 students, over 95% of whom qualify for free and reduced lunch. The property was purchased many decades ago when the lumber mills were booming and so was the population. It was built as a second middle school, and the grounds had plenty of room to build a second high school. But the anticipated boom never came, and the property eventually became an elementary school surrounded by a small field and a 50-acre forest. At some time in the past, an enterprising teacher had cut trails through the forest for student access. When that teacher retired, the trails largely fell into disuse.

The Seed of an Idea

In Oregon third-grade students must perform a writing work sample each year. The topic in North Bend, which had been handed down from previous teachers, was invasive species. The class would work together to write a paper on an invasive species found in Florida, then apply their writing process knowledge to produce a sample on an Oregon invasive. They were given three curated sources created by using a lexile adjuster on the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife website. This project existed in a relative vacuum– invasive species were not mentioned before or after the work sample. Its only connection to the rest of the curriculum was the writing style. The students were interested in the topic and produced decent work, but Edward Nichols thought they could do better. He had long noticed multiple patches of Scotch broom growing just off the school playground. This invasive plant out-competes native ones and does not provide food or useful habitat for other native species. He wondered if they could do something with this to enhance the writing work sample and turn it from a stand-alone project to something more meaningful.

Fertile Ground

That summer, Edward attended a Diack Training held at Silver Falls State Park. In addition to providing excellent professional development on how to perform field-based inquiry with your students, it is also a place where you get to meet other educators with similar mindsets.

A chance conversation with Julia Johanos, who was then serving as Siuslaw National Forest’s Community Engagement and Education Coordinator, led to the idea of having an assembly on invasive plants for all students at North Bay Elementary. Edward was also a member of the Rural STEAM Leadership Network, and he met Jim Grano in their monthly Zoom sessions. Jim is a retired English teacher who is now focused on getting students outside. He has helped several schools in the Mapleton area start Stream Teams, which got students outside restoring stream habitat and collecting data on salmon. He routinely led student groups into the field to remove English ivy and Scotch broom. Edward invited him to help lead a similar event at North Bay.

The Big Event

The Big Event

After weeks of planning, North Bay held a service learning day on March 17, 2023. The kickoff happened the day before when Julia Johanos led an engaging school-wide assembly on why invasive species are bad for our environment. The next day, the entire school participated in removing Scotch broom from the forest. The students came out one grade band at a time in 45-minute shifts. Each grade had a different task. Kindergarten students pulled the seedling Scotch broom by hand. Slightly larger stalks required “buddy pulls”, where two students worked together. Fourth and Fifth grades used weed wrenches to remove bigger plants. Alice Yeats from the South Slough NERR briefed each group on safety. And dozens of parent volunteers kept everybody safe. The Coos Watershed Association donated native plants, and the second grade came out at the end of the day to plant coyote bushes and red flowering currant, native strawberries, Oregon grape, and a variety of evergreen trees in the spaces the broom used to occupy. After school, Christina Geierman, a science teacher at North Bend High School, brought high school volunteers from the Science National Honor Society to help pull the biggest broom of all and clean up after the event.

Sustaining the Excitement

It is a tradition at North Bay to have a variety of fun activities for the last day of school. This year, in addition to the stalwarts of bubble soap, bicycles, and bounce houses, the event also contained a Scotch broom pull led by Jim Grano. Students could do whatever activity they chose, and many students chose to remove the broom from the edge of the playground. A representative from OSU Extension was also there, showing the kids how to make bird feeders, and folks from the South Slough NERR returned to lead nature hikes. The Confederated Tribes of Coos, Lower Umpqua, and Siuslaw Indians (CTCLUSI) also ran a booth and taught students about conservation and had them play a native game called nauhina’nowas (shinny), which involved using tall, carved sticks to pass and catch two balls connected by twine.

A second, school-wide Scotch broom pull occurred this past fall. Edward also started a Forestry Club at North Bay, which featured guest speakers from the Bureau of Land Management and had the students planting more native species. Plans are underway to have a school-wide pull each spring and a forestry club each fall to plant native species just before the rainy season hits.

Applying Their Knowledge

Applying Their Knowledge

Students participating in the Scotch broom pull apply their classroom knowledge in various ways. In mathematics, they record and tally the number of plants removed, practicing authentic math skills. They observe and document the plant’s lifecycle during the pull, connecting classroom biology lessons to real-world applications. North Bay uses the Character Strong curriculum to address social-emotional learning, and the broom pull allows students to apply traits like perseverance, cooperation, and service. Students can immediately and directly see the results of their efforts when they go outside for recess. This gives them a sense of pride in their accomplishments. There have been many reports of students educating their parents about why Scotch broom should be removed from the environment and even a few tales of students removing invasive plants from their own properties.

While participating in the Scotch broom pull, the students met a variety of scientists and conservationists. They were able to make a connection between this sort of work and future job opportunities. Jim Grano showed them that, if you feel passionately about something, you can make a difference as a volunteer. Alice Yeats, Julia Johanos, and Alexa Carleton from the Coos Watershed Association showed them that women can be scientists and do messy work in the field just as well as men can. Although it will take many years to tell, we hope that a few students will be inspired by this work to pursue careers in natural resources management.

Into the Future

This past fall, North Bay was named a NOAA Ocean Guardian School. This means that NOAA will provide the funds necessary to carry this project forward and expand it. The grant is renewable for up to five years. This spring, a group of students from North Bay will host a booth at Coos Watershed’s annual Mayfly Festival. There, students will present their project to members of the public and urge them to remove Scotch broom and other invasives from their own properties.

This spring, the North Bend High School Science National Honor Society (SNHS) will partner with North Bay students for a Science Buddies Club that will take place after school. Thanks to a Diack Grant awarded to Christina Geierman and Jennifer Hampel, the SNHS has a variety of Vernier probes and other devices that can be used to collect data in the forest. In the first meeting, the North Bay students will guide the high schoolers down the forest trails and describe their Scotch broom project. The SNHS members will show them how the probes work and what data we can gather. The guiding question will be, “Why do Scotch broom live in some areas of the forest, but not others?” The students will come up with hypotheses, focusing on one variable like temperature, light availability, etc. and then work together to gather and analyze the data. Students will present their data in a poster at the Mayfly Festival and possibly the State of the Coast Conference.

Members of the North Bend High School Science National Honor Society and family volunteers have reopened the trails through the forest. Plans are underway to expand these trails and partner with the CTCLUSI to create signage. The forest is being used by the school once again. Classrooms that earn enough positive behavior points can choose nature walks through the forest as potential rewards. Dysregulated students are taken down the path to calm them. Increasing student and community use of the forest is one of our future goals.

Edward Merrill Nichols is a 3rd-grade Teacher at North Bay Elementary in North Bend, Oregon. Growing up on the southern coast of Oregon instilled in him a love of and respect for his natural surroundings. With over six years of experience, he fosters student growth through engagement and respect. Edward actively engages in STEM education, leading Professional Development sessions and extracurricular clubs. He holds a Bachelor of Science in Education and a Master of Science in K-8 STEM Education from Western Oregon University.

Edward Merrill Nichols is a 3rd-grade Teacher at North Bay Elementary in North Bend, Oregon. Growing up on the southern coast of Oregon instilled in him a love of and respect for his natural surroundings. With over six years of experience, he fosters student growth through engagement and respect. Edward actively engages in STEM education, leading Professional Development sessions and extracurricular clubs. He holds a Bachelor of Science in Education and a Master of Science in K-8 STEM Education from Western Oregon University.

Christina Geierman has taught physics, biology, and dual-credit biology at North Bend High School for eleven years. She is a published scientist, a proud union member, a decent trombone player, and a world traveler. She enjoys spending time outside with her husband, Edward Nichols, and dog, Aine.

Christina Geierman has taught physics, biology, and dual-credit biology at North Bend High School for eleven years. She is a published scientist, a proud union member, a decent trombone player, and a world traveler. She enjoys spending time outside with her husband, Edward Nichols, and dog, Aine.

by editor | Sep 7, 2025 | Critical Thinking, Environmental Literacy, Experiential Learning, Integrating EE in the Curriculum, K-12 Activities, Language Arts, Learning Theory

by Jim McDonald

The demands on classroom teachers to address a variety of different subjects during the day means that some things just get left out of the curriculum. Many schools have adopted an instructional approach with supports for students that teach reading and math, with the addition of interventions to teach literacy and numeracy skills which take up more time in the instructional schedule. In some of the schools that I work with there is an additional 30 minutes a day for reading intervention plus 30 more minutes for math intervention. So, we are left with the question, how do I fit time for science or environmental education into my busy teaching schedule?

In a recent STEM Teaching tools brief on integration of science at the elementary level, it was put this way:

We do not live in disciplinary silos so why do we ask children to learn in that manner? All science learning is a cultural accomplishment and can provide the relevance or phenomena that connects to student interests and identities. This often intersects with multiple content areas. Young children are naturally curious and come to school ready to learn science. Leading with science leverages students’ natural curiosity and builds strong knowledge-bases in other content areas. Science has taken a backseat to ELA and mathematics for more than twenty years. Integration among the content areas assures that science is given priority in the elementary educational experience (STEM Teaching Tool No. 62).

Why does this matter? Educators at all levels should be aware of educational standards across subjects and be able to make meaningful connections across the content disciplines in their teaching. Building administrators look for elementary teachers to address content standards in math, science, social studies, literacy/English Language arts at a minimum plus possibly physical education, art, and music. What follows are some things that elementary teachers should consider when attempting integration of science and environmental education with other subjects.

Things to Consider for Integration

The integration of science and environmental education concepts with other subjects must be meaningful to students and connect in obvious ways to other content areas. The world is interdisciplinary while the experience for students and teachers is often disciplinary. Learning takes place both inside and outside of school. Investigations that take place outside of school are driven by people’s curiosity and play and often cut across disciplinary subjects. However, learning in school is often fragmented into different subject matter silos.

Math and reading instruction dominate the daily teaching schedule for a teacher because that is what is evaluated on standardized tests. However, subjects other than ELA and math should be kept in mind when considering integration. Social studies and the arts provide some excellent opportunities for the integration of science with other content areas. In the NGSS, the use of crosscutting concepts support students in making sense of phenomena across science disciplines and can be used to prompt student thinking. They can serve as a vehicle for teachers to see connections to the rest of their curriculum, particularly English/Language Arts and math. Crosscutting concepts are essential tools for teaching and learning science because students can understand the natural world by using crosscutting concepts to make sense of phenomena across the science disciplines. As students move from one core idea to another core idea within a class or across grade-levels, they can continually utilize the crosscutting concepts as consistent cognitive constructs for engaging in sense-making when presented with novel, natural phenomena. Natural phenomena are observable events that occur in the universe and we can use our science knowledge to explain or predict phenomena (i.e., water condensing on a glass, strong winds preceding a rainstorm, a copper penny turning green, snakes shedding their skin) (Achieve, 2016).

Reading

Generally, when I hear about science and literacy, it involves helping students comprehend their science textbook or other science reading. It is a series of strategies from the field of literacy that educators can apply in a science context. For example, teachers could ask students to do a “close reading” of a text, pulling out specific vocabulary, key ideas, and answers to text-based questions. Or, a teacher might pre-teach vocabulary, and have students write the words in sentences and draw pictures illustrating those words. Perhaps students provide one another feedback on the effectiveness of a presentation. Did you speak clearly and emphasize a few main points? Did you have good eye contact? Generally, these strategies are useful, but they’re not science specific. They could be applied to any disciplinary context. These types of strategies are often mislabeled as “disciplinary literacy.” I would advocate they are not. Disciplinary literacy is not just a new name for reading in a content area.

Scientists have a unique way of working with text and communicating ideas. They read an article or watch a video with a particular lens and a particular way of thinking about the material. Engaging with disciplinary literacy in science means approaching or creating a text with that lens. Notably, the text is not just a book. The Wisconsin DPI defines text as any communication, spoken, written, or visual, involving language. Reading like a scientist is different from having strategies to comprehend a complex text, and the texts involved have unique characteristics. Further, if students themselves are writing like scientists, their own texts can become the scientific texts that they collaboratively interact with and revise over time. In sum, disciplinary literacy in science is the confluence of science content knowledge, experience, and skills, merged with the ability to read, write, listen, and speak, in order to effectively communicate about scientific phenomena.

As a disciplinary literacy task in a classroom, students might be asked to write an effective lab report or decipher the appropriateness of a methodology explained in a scientific article. They might listen to audio clips, describing with evidence how one bird’s “song” differs throughout a day. Or, they could present a brief description of an investigation they are conducting in order to receive feedback from peers.

Social Studies

You can find time to teach science and environmental education and integrate it with social studies by following a few key ideas. You can teach science and social studies instead of doing writer’s workshop, choose science and social studies books for guided reading groups, and make science and social studies texts available in your classroom library.

Teach Science/Social Studies in Lieu of Writer’s Workshop: You will only need to do this one, maybe two days each week. Like most teachers, I experienced the problem of not having time to “do it all” during my first year in the classroom. My literacy coach at the time said that writer’s workshop only needs to be done three times each week, and you can conduct science or social studies lessons during that block one or two times a week. This was eye-opening, and I have followed this guidance ever since. My current principal also encouraged teachers to do science and social studies “labs” once a week during writing time! Being able to teach science or social studies during writing essentially opens up one or two additional hours each week to teach content! It is also a perfect time to do those activities that definitely take longer than 30 minutes: science experiments, research, engagement in group projects, and so forth. Although it is not the “official” writers workshop writing process, there is still significant writing involved. Science writing includes recording observations and data, writing steps to a procedure/experiment, and writing conclusions and any new information learned. “Social studies writing” includes taking research notes, writing reports, or writing new information learned in a social studies notebook. Students will absolutely still be writing every day.

Choose Science and Social Studies Texts for Guided Reading Groups: This suggestion is a great opportunity to creatively incorporate science and social studies in your weekly schedule. When planning and implementing guided reading groups, strategically pick science and social studies texts that align to your current unit of study throughout the school year. During this time, students in your guided reading groups can have yet another opportunity to absorb content while practicing reading strategies.

Make Science and Social Studies Texts Available and Accessible in Your Classroom Library: During each unit, select texts and have “thematic unit” book bins accessible to your students in a way that is best suited for your classroom setup. Display them in a special place your students know to visit when looking for books to read. When kids “book-shop” and choose their just-right books for independent reading, encourage them to pick one or two books from the “thematic unit” bin. They can read these books during independent reading time and be exposed to science and social studies content.

Elementary Integration Ideas

Kindergarten: In a kindergarten classroom, a teacher puts a stuffed animal on a rolling chair in front of the room. The teacher asks, “How could we make ‘Stuffy’ move? Share an idea with a partner”. She then circulates to hear student talk. She randomly asks a few students to describe and demonstrate their method. As students share their method, she will be pointing out terms they use, particularly highlighting or prompting the terms “push” and “pull”. Next, she has students write in their science notebooks, “A force is a push or a pull”. This writing may be scaffolded by having some students just trace these words on a worksheet glued into the notebook. Above that writing, she asks students to draw a picture of their idea, or another pair’s idea, for how to move the animal. Some student pairs that have not shared yet are then given the opportunity to share and explain their drawing. Students are specifically asked to explain, “What is causing the force in your picture?”.

For homework, students are asked to somehow show their parents a push and a pull and tell them that a push or a pull is a force. For accountability, parents could help students write or draw about what they did, or students would just know they would have to share the next day.

In class the next day, the teacher asks students to share some of the pushes and pulls they showed their parents, asking them to use the word force. She then asks students to talk with their partner about, “Why did the animal in the chair sometimes move far and sometimes not move as far when we added a force?”. She then asks some students to demonstrate and describe an idea for making the animal/chair farther or less far; ideally, students will push or pull with varying degrees of force. Students are then asked to write in their notebooks, “A big force makes it move more!” With a teacher example, as needed, they also draw an image of what this might look like.

As a possible extension: how would a scientist decide for sure which went further? How would she measure it? The class could discuss and perform different means for measurement, standard and nonstandard.

Fourth Grade Unit on Natural Resources: This was a unit completed by one group of preservice teachers for one of my classes. The four future elementary teachers worked closely in their interdisciplinary courses to design an integrated unit for a fourth-grade classroom of students. The teachers were given one social studies and one science standard to build the unit around. The team of teachers then collaborated and designed four lessons that would eventually be taught in a series of four sessions with the students. This unit worked to seamlessly integrate social studies, English language arts, math, and science standards for a fourth-grade classroom. Each future teacher took one lesson and chose a foundation subject to build their lesson upon. The first lesson was heavily based on social studies and set the stage for the future lessons as it covered the key vocabulary words and content such as nonrenewable and renewable resources. Following that, students were taught a lesson largely based on mathematics to better understand what the human carbon footprint is. The third lesson took the form of an interactive science experiment so students could see the impact of pollution on a lake, while the fourth lesson concluded with an emphasis on language arts to engage students in the creation of inventions to prevent pollution in the future and conserve the earth’s resources. Contrary to the future educators’ initial thoughts, integrating the various subject areas into one lesson came much more easily than expected! Overall, they felt that their lessons were more engaging than a single subject lesson and observed their students making connections on their own from previously taught lessons and different content areas.

References

Achieve. (2016). Using phenomena in NGSS-designed lessons and units. Retrieved from https://www.nextgenscience.org/sites/default/files/Using%20Phenomena%20in%20NGSS.pdf

Hill, L., Baker, A., Schrauben, M. & Petersen, A. (October 2019). What does subject matter integration look like in instruction? Including science is key! Institute for Science + Math Education. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Retrieved from: http://stemteachingtools.org/brief/62

Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction. (n.d.) Clarifying literacy in science. Retrieved from: https://dpi.wi.gov/science/disciplinary-literacy/types-of-literacy

Jim McDonald is a Professor of Science Education at Central Michigan University in Mt. Pleasant, Michigan. He teaches both preservice teachers and graduate students at CMU. He is a certified facilitator for Project WILD, Project WET, and Project Learning Tree. He is the Past President of the Council for Elementary Science International, the elementary affiliate of the National Science Teaching Association.

Jim McDonald is a Professor of Science Education at Central Michigan University in Mt. Pleasant, Michigan. He teaches both preservice teachers and graduate students at CMU. He is a certified facilitator for Project WILD, Project WET, and Project Learning Tree. He is the Past President of the Council for Elementary Science International, the elementary affiliate of the National Science Teaching Association.

It is a warm summer day at Silver Falls State Park and a group of teachers are conducting a macroinvertebrate study on the abundance and richness of species around the swimming hole. The air is filled with sounds of laughter from children playing, parents conversing on the bank, and the gentle babble of the stream below the dam. The teachers, armed with Dnets, clipboards, and other sampling equipment, move purposefully through the water collecting aquatic species. Being a leader at this unique workshop, I am there to support the teacher’s inquiry project and also help brainstorm ways to bring this type of work back to their classrooms.

It is a warm summer day at Silver Falls State Park and a group of teachers are conducting a macroinvertebrate study on the abundance and richness of species around the swimming hole. The air is filled with sounds of laughter from children playing, parents conversing on the bank, and the gentle babble of the stream below the dam. The teachers, armed with Dnets, clipboards, and other sampling equipment, move purposefully through the water collecting aquatic species. Being a leader at this unique workshop, I am there to support the teacher’s inquiry project and also help brainstorm ways to bring this type of work back to their classrooms. Teachers often want to backwards plan, knowing the end product their students will experience and learn. But this type of scientific inquiry requires us to let go of control so that students can ask authentic, meaningful questions that are not yet answered. Teachers come to learn that teaching the process of science is often more valuable than teaching the content. They are engaging in the work of true scientists and learning how to be curious, lifelong learners along the way. Being a part of inspiring projects and trips such as these is an experience that teachers, students, and even parent volunteers will remember for years to come. As an upper elementary teacher myself, I often hear about the power of our work when families come back to visit and reminisce about their time in my classroom. I know that this work will impact future generations and their enthusiasm for science learning. Not only that, we are teaching students to do, read and understand the work of a scientist so they can make informed choices in their adult lives.

Teachers often want to backwards plan, knowing the end product their students will experience and learn. But this type of scientific inquiry requires us to let go of control so that students can ask authentic, meaningful questions that are not yet answered. Teachers come to learn that teaching the process of science is often more valuable than teaching the content. They are engaging in the work of true scientists and learning how to be curious, lifelong learners along the way. Being a part of inspiring projects and trips such as these is an experience that teachers, students, and even parent volunteers will remember for years to come. As an upper elementary teacher myself, I often hear about the power of our work when families come back to visit and reminisce about their time in my classroom. I know that this work will impact future generations and their enthusiasm for science learning. Not only that, we are teaching students to do, read and understand the work of a scientist so they can make informed choices in their adult lives. Tina Allahverdian is passionate about connecting students with science in the natural world. When not teaching fifth graders, she can be found reading in a hammock, kayaking through Pacific Northwest waters, or hiking in the mountains. She currently teaches in West Linn, Oregon, and resides in SE Portland with her husband, twin boys, and their dog, Nalu.

Tina Allahverdian is passionate about connecting students with science in the natural world. When not teaching fifth graders, she can be found reading in a hammock, kayaking through Pacific Northwest waters, or hiking in the mountains. She currently teaches in West Linn, Oregon, and resides in SE Portland with her husband, twin boys, and their dog, Nalu.