by editor | Jul 28, 2014 | K-12 Classroom Resources

Teaching Stewardship Through Native Legend

Abstract: This article provides the reader with a general background of Alaska Native education and resource conservation, focusing on southeast Alaska cultures. European contact severed these education models by creating government schools. Since then Alaska Natives have worked to balance Native culture with western education. A synopsis of several legends which speak to natural resource conservation is presented with the conservation ethic discussed. The use of these types of legends in the classroom is encouraged as a means of bringing Native values and lessons into the classroom as one means of making education relevant to Native students. The lesson from this discussion can be applied to other indigenous groups.

by Dolly Garza

To address environmental stewardship and education among Alaska Natives it is necessary to start with a brief review of Native cultures and educational systems.

Alaska Natives have lived along this northern coast for thousands of years. Groups developed cultures that revolved around local resources. The Haida, Tlingit, Tsimshian, Eyak, Supiak, Alutiiq, Yupik, Siberian Yupik, Inupiat, and the Athabascan learned how to use surrounding resources for food, clothing, shelter, transportation, regalia, and the arts.

Careful observation of animals, plants and weather over the seasons provided the knowledge base to know when to gather, or when to move. This accumulation of knowledge was necessary to the survival of the community; therefore, it was necessary to pass the knowledge from generation to generation. Knowledge was transferred through oration, observation, and action. Written instructions were generally unknown.

In southeast Alaska, among the Haida, Tlingit, and Tsimshian, children did not learn from their parents. It was generally understood that parents loved the children too much and would spoil them. It was the job of the aunties and uncles of the clan to teach the children important knowledge and skills.

Southeast Culture and Stewardship

Much of Southeast Alaska where I come from was owned or occupied by the Tlingit and Haida. Tlingit historians will tell you that many areas and the associated resources were part of a clan’s property. Their territory included permanent village sites. However a clan’s use,

territorial rights, and stewardship extended beyond these typical areas to seaweed picking areas, berry picking areas, and into the rivers and ocean with herring egg gathering sites, salmon streams, seal hunting rookeries, and halibut fishing grounds.

Anthropologist and early explorers documented many types of conservation techniques and practices. Legends such as Moldy Salmon or Herring Rock were lessons which Elders told to teach youngsters to respect and properly use salmon, herring, and other resources. Clan leaders would decide when fishing would begin and end, and determine other resource harvesting methods. Clan members understood their obligation to follow these rules and rituals. European Contact

In 1876 Alaska were purchased by the United States from Russian, an action which was protested by the Tlingit Nation in Sheetka or Sitka, Alaska. The Russian had a stronghold to very limited sites in the Sitka, Kodiak, and Aleutians areas.

The early traders brought beads, bullets, alcohol, and diseased blankets. In addition, early traders were sick from months on ships with poor water and nutrition. They passed along their sicknesses which were new, and tragic, to Native populations.

The ravages of diseases in the 1800’s have had one of the largest impacts on Alaska Native cultures. Indigenous populations were reduced to less then 1⁄2 the estimated pre-contact populations. In some areas entire villages died from small pox or influenza. Much knowledge was lost with the death of each Elder, hunter, or mother.

Gold miners, fishing companies, and pioneers followed. The military, preachers, and teachers accompanied these early arrivers. The military came to protect the white people, the Christians to convert, and the teachers to civilize the Native.

The Native peoples generally were moved from their traditional sites to designated communities where religion and education could be taught. In many areas the traditional clan structure of government was abandoned. The new education and religion systems were embraced in fear of the ravages of disease. Natives believed they would better survive under this new system, since their old plant medicines and ceremonies did not save them from new diseases.

Early Education Systems

After being taken away and educated at government schools, many Natives made it back home and were expected to live a new life. They tried to be religious and teach their children English and new cultural ways. This assimilation process was only partially successful. Many such as my grandmother Elizabeth were forced to stop speaking Haida to her children. She was devoted to her church. Her children were sent to boarding school and came home years later.

When children were sent off to school parents had no control over what they did, what they wore, what they were taught, or what they were led to believe. This generation, my mothers, came home and began their own lives. They sent their children to school and believed that this is what should be done. “Send your children to school and expect the system to do everything”. Many in my mother’s age believed they had no right to interfere with their children’s education; and for the most part this was true at the time.

Many of the “educated” from my mother’s generation came home and believed that their parents lived backward lives; or if they tried to live this new life they found their were no jobs, and no money to buy all these new commodities. Many put this education aside and went back to living the old way: hunting, fishing, putting up food, living in old ramshackle houses, some with no running water, or sewer.

Current Educational Efforts

In some senses Native people have come full circle. Part out of necessity, and a great part out of love for our culture and land, we continue to live simple lifestyles. Alaska Natives are working to balance Native culture and mainstream education.

However there is still the early education mantra that prevails among the conscious or subconscious of our Elders and thus our community: “Native people must be civilized and cleansed of their former ways”, “Western education is better”.

Today many Alaska Natives still believe that the western education is better. They see education as severed from their daily life and do not feel that they can add to this educational process. Children come to school still thinking their home life, and cultural dance or stories, are archaic and not important. This leads to poor self-esteem and often, an aversion to Native ways. It is important to help Native students understand the value of cultures.

Recent efforts such as those of the Alaska Rural Systemic Initiative, funded by the NSF, promotes incorporating Native science, knowledge, and education skills into the classroom as a means of making the science relevant to local areas and helping students understand the value of parental knowledge and their culture. One part of this broad educational effort focused on Native stories or legends that were taught to children. While these stories are entertaining their main purpose has been to teach respect.

Native Legends as Teaching Tools

As an example of ritual, in some areas salmon would be harvested only after the first salmon went upstream and were properly honored through dance and ceremony. It was told that this was done so that the spirit of the salmon would return to its brothers and sisters and report that these were good people and that the salmon should give themselves to these people.

Someone would notice the first salmon coming up stream and alert the community. Eagle down was gathered, regalia donned, and people commenced to the river. Songs were sung, and words were spoken to the salmon. Respect was shown. After this, fishing could take place at the chief’s orders. In the time it took to set up these ceremonies, hoards of salmon went up the river. Today we refer to this as escapement; the necessary brood-stock to ensure continued survival of the salmon. Without the eagle down, this is a standard fishery management practice.

In the Moldy Salmon story a young boy is taken to live with the salmon people after he disrespects salmon. Upon his return to his people he educates them on how important it is to eat all of the salmon and to respect salmon.

In the herring rock story a man is turned into a stone after he disobeys the clan leaders rule to not fish for herring after nightfall. The rest of the community understands the consequences of fishing after nightfall as they pass by this rock everyday. The rock was known to recent time in the Sitka area until it was covered during a construction project. Herring biologists know that herring school up and rise to the surface at night. During this time they are very susceptible to over harvest. A “legend” as it is now called served as a regulation.

Summary

As we teach environmental ethics to our young it is well worth using Native or other indigenous folklore to highlight traditional means of conservation. It is important to keep Native children in the folds of education and help non-Natives to understand that Natives were not savages, but lived in balance with their environment.

But as we use legends we must remember to respect tribal and clan property rights. I have not written any legend in full nor do we have permission to commercialize these legends for

profit. However the use of these legends as an educational tool is welcomed by most Elders and tribes.

Dolores “Dolly” Garza is a full-time Professor for the University of Alaska Marine Advisory Program. She has worked in Kotzebue and Sitka and now works in Ketchikan as a Marine Advisory agent, interfacing European science with Alaska’s marine resource users in the areas of subsistence management, marine mammal management and marine safety. This article reprinted from proceedings of the 2006 North American Association for Environmental Education annual conference in Anchorage, Alaska.

by editor | Jul 25, 2014 | K-12 Classroom Resources

Classify It!- Learn about animal classifications through a guided discussion of the book Forest Night, Forest Bright. http://dawnpub.com/activities/Classify_Activity.pdf

Classify It!- Learn about animal classifications through a guided discussion of the book Forest Night, Forest Bright. http://dawnpub.com/activities/Classify_Activity.pdf

by editor | Jul 21, 2014 | K-12 Classroom Resources

Climate Change Education

SWEet!: Using Cascade Snowpack to Teach Climate Change

by Padraic Quinn, Rachel Carson Environmental Middle School

Padraic_Quinn@beaverton.k12.or.us

Illustration by Bill Reiswig

Three years ago I was given the opportunity to learn with the scientific leaders of climate change research as part of a teacher-research partnership through NASA, Oregon State University and the Oregon Natural Resources Education Program (ONREP). I heard scientists talk about how forests act as carbon sinks or carbon sources, how LANDSAT data are showing us changes to our landscape, how ocean currents are affecting the availability of copepods eaten by salmon, and how the growth rings in the ear bone of a fish can be studied and correlated with the growth rings of trees on the nearby coast. All of these researchers were making discoveries that played a role in our knowledge of climate change. In addition, teachers were assigned to a scientist each year to conduct research over a two-week period. This allowed both the teachers and researchers to discuss their work and determine ways that it could be transferred from climate researcher work to middle school student work. This sharing of information included access to the scientists and their work, even when I returned to my classroom.

Transferring Professional Development to the Classroom

A significant portion of my classroom science curriculum is spent on independent research projects where students work through the inquiry process to answer a question to a problem on a science topic of their choice. Prior to starting our projects this year I assessed students on their graphing and analysis skills by teaching lessons on climate change in the Northwest, primarily using the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) SNOTEL system. This automated system, under the technical guidance of the National Water and Climate Center (NWCC) provides snowpack and climate data in the Western U.S. and Alaska. SNOTEL provides real-time data that is critical for understanding future water supplies and allows my students exposure to natural resource issues that will directly affect them and their families. Based on my experiences working with snow pack research, I designed a multiday lesson on climate change that used SNOTEL data to form the basis of the students’ inquiry.

Climate Change and NW Snowpack Lessons

Day 1

Each student was asked to build a concept map for climate change showing connections among different components. Examples were given for a concept we had just finished studying (photosynthesis) so they were clear on how to see and depict interactions. The concept maps varied drastically, partially due to the fact that my classes include a mix of 6 – 8 graders but also because of the wide range of knowledge about climate change knowledge among my students. The discussion after the students completed their concept map and pretest was valuable, with many students wanting to share, ask questions and verbalize their current understanding of climate change.

Day 2

Students were excited when they sat down, and I was in the back of the room with a very loud snow-cone machine. After they got over the initial disappointment of not getting a refreshing snow-cone, each table group was asked to agree on the volume of “snow” that was in the beaker I had filled and placed on their table. Students recorded their information along with a definition of SWE or Snow Water Equivalent. Our basic definition was the amount of water in the snow. Students also made a prediction of the SWE for the “snow” that was on their table. At the end of class, after melting, students determined the percent water content in their snow.

To show a real life example on a large scale of global climate change and melting I had students watch the TED Talk, “James Balog: Time-lapse proof of extreme ice loss”. Balog shows photographs from the Extreme Ice Survey that he began in 2005 and shared in his TED Talk from 2009. Students were asked to write down new information, “WOW” information and questions they had from the talk. Connections were made since some students had been to Alaska, while others had been in the Cascades Mountains; but the majority of the students did not realize that glaciers were present in the mountains located just 65 miles from where they were sitting in Beaverton, Oregon.

Days 3 & 4

To help connect students to their surroundings I had them pick an Oregon SNOTEL site out of a hat. The sites didn’t make sense to them yet but the names are intriguing with the likes of Jump Off Joe, Blazed Alder, Bear Grass and Mud Ridge. Students went online to gather general information about their SNOTEL site such as county, latitude-longitude, and elevation. The students also collected SWE, snow depth, YTD precipitation, and Max., Min. and Average Temperature (see attached student activity sheet). To get a view of the historical context of how SWE has changed over time students collected mean SWE for March in every year that SNOTEL data have been collected. In most cases this was approximately 1978. Students found wide variations in SWE from year to year but soon were asking about specific years from other sites and realized how data were similar from site to site. Many discussions revolved around why such large fluctuations exist, trends over time, temperature’s impact on SWE and elevation impact on SWE. These discussions were difficult for even some of the more accomplished 8th graders, but interest did not diminish due to complexity. Students graphed data, wrote a short analysis and compared data with another student whose site elevation differed (+/-2000’) from their own site.

Adopt-a-SNOTEL site: Long Term Snowpack & Water Availability Activities

As a follow-up to this activity students have been monitoring their SNOTEL sites since November daily for SWE, snow depth, YTD Precipitation and Observed Temperature. (See attached student monitoring sheet.) This work has continued to keep students interested and active in local mountain snowfall and their own SNOTEL site. Each month I am asking students to conduct activities and answer questions on their SNOTEL data. This includes graphing one or more of the parameters, discussing monthly trends in the data, comparing site data with another student and finding sciences article related to snowpack, glaciers and climate change. Students will conduct this activity throughout the winter and spring months as a way to continue their learning on climate change, make a connection to their sense of place and better understand how their water supply will be affected in the short and long term.

The range of benefits to me and my students provided by the Researcher-Teacher Partnerships project have been immeasurable. I have been given open access to an elite scientific community, the collaboration among educators has been inspiring, and my current and future students will continue to learn as researchers.

References

Natural Resources Conservation Service. (2013) SNOTELand Snow Survey & Water Supply Forecasting Brochure. National Weather and Climate Center, Portland, Oregon

http://www.wcc.nrcs.usda.gov/snow/about.html

Natural Resources Conservation Service SNOTEL Data, http://www.wcc.nrcs.usda.gov/snow/

TED Conferences, LLC. (2009) James Balog: Time-lapse proof of extreme ice loss http://www.ted.com/talks/james_balog_time_lapse_proof_of_extreme_ice_loss.html

Science expertise was provided by the following Oregon State University Faculty: Dr. Anne Nolin – Professor and Travis Roth-Doctoral Student in the College of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Sciences

Acknowledgements

These lessons were created using information learned in the Oregon Natural Resources Education Program’s Researcher Teacher Partnerships: Making global climate change relevant in the classroom project. This project was supported by a NASA Innovations in Climate Education award (NNXI0AT82A).

Student Activity Sheet Attached

SNOTEL Activity for Oregon.docx

SNOTEL MONITORING SHEET.docx

SNOTEL SWE for Oregon name: _______________________

SITE MONITORING

Use this to record data for your SNOTEL site for the next month. In the table below you will find the information you will need to record for your site. This should be collected at least once per week for each day that week.

1. Go to Google Search and type Oregon SNOTEL

2. Click on first site shown which will be a map of Oregon

3. Use the drop down menu Select a SNOTEL Site to find your site by name. Or if you know where your site is located you can click on the correct red dot on the map.

Site Name: ____________________________________ Site Number: ___________________________

County: _______________________________________ Elevation: _______________________________

Latitude: _____________________________________ Longitude: _______________________________

5. Click on Last 7 Days under the Daily column for Snow Water Equivalent. Record the following.

| Date |

Snow Water

Equivalent

(in) |

Snow

Depth

(in) |

Year-to-Date

Precipitation

(in) |

Observed

Temp

(degF) |

by editor | Jul 17, 2014 | K-12 Classroom Resources

Special thanks to Phyllis Dermer and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)

1. Melinda Gray Ardia Environmental Foundation Grants

K-12 teachers are invited to apply for grants to develop or implement environmental curricula that integrate hands-on ecology exercises into the classroom. To facilitate learning and student empowerment, environmental curricula should be holistic and strive to synthesize multiple levels of learning (facts, concepts, and principles), often including experiential integrated learning and problem solving. The deadline for pre-proposals is September 14, 2014.

K-12 teachers are invited to apply for grants to develop or implement environmental curricula that integrate hands-on ecology exercises into the classroom. To facilitate learning and student empowerment, environmental curricula should be holistic and strive to synthesize multiple levels of learning (facts, concepts, and principles), often including experiential integrated learning and problem solving. The deadline for pre-proposals is September 14, 2014.

http://www.mgaef.org/application.htm

2. Oregon Coast Education Program Summer Workshop – Oregon

2. Oregon Coast Education Program Summer Workshop – Oregon

Science Educators in grades 6-12 can join the educators at the Oregon Coast Education Program, August 13-15, 2014 in Charleston, Oregon. Topics include coastal ecology and habitats, impacts and solutions including climate connections, working with data sets, and making connections to your schools. Participants will receive continued support during the school year. A stipend may be available.

http://www.pacname.org/news.shtml

3. Biomimicry Education Network

3. Biomimicry Education Network

The Biomimicry Education Network (BEN) is a global community of teachers who are integrating biomimicry into K-12 classrooms, university courses, and informal learning environments. The website and blog support members by providing curriculum and resource downloads, a platform to connect with colleagues, and news and information. Check out the on-line flip-book, Biomimicry in Youth Education. Note: free registration is required.

http://ben.biomimicry.net/

4. Bird Song Hero

4. Bird Song Hero

The All About Bird Biology team from Cornell has developed the game, Bird Song Hero, asking players to match the song they’re hearing to one of three visual representations of the sound. The game puts the visual side of the brain to work.

http://biology.allaboutbirds.org/bird-song-hero/

5. Climate Change Indicators

The third edition of EPA’s Climate Change Indicators in the United States presents 30 indicators, each describing trends related to the causes and effects of climate change. It focuses primarily on the United States, but in some cases global trends are presented to provide context or a basis for comparison. Sections include Understanding Greenhouse Gases, Snow and Ice, Ecosystems, and more.

http://www.epa.gov/climatechange/science/indicators/download.html

6. Global Forest Watch

The World Resources Institute hosts this dynamic forest monitoring and alert system. Global Forest Watch unites satellite technology, open data, and crowdsourcing to offer access to timely and reliable information about forests. The interactive map of the world includes features that allow users to learn about tree cover loss over time, success stories from around the world, and more. Visitors must agree to terms of use before accessing the website.

http://www.globalforestwatch.org/

7. Marine CSI

7. Marine CSI

Marine CSI: Coastal Science Investigations is offering free sample lessons from their two books. Each book contains over 50 lessons divided into eight units correlated to the Next Generation Science Standards. Amazon offers a preview of the books on their website. Kimberly Belfer is offering a sample lesson; contact her with your grade level of preference and your location.

http://www.amazon.com/Marine-CSI-Coastal-Science-Investigations/dp/1492840718

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Marine-CSI-Coastal-Science-Investigations/dp/1497427223

Contact Kimberly Belfer at kimberly.belfer@gmail.com

8. Resources for STEM Education

The NSF hosts this K-12 Resources for STEM Education website with links to resources and findings generated through educational research and development projects funded in part by the National Science Foundation. Materials include professional development, instructional materials, assessment, and research syntheses.

http://www.nsfresources.org/home.cfm

9. Urban Environmental Education Lesson Plans

These 26 lesson plans are an outcome of the 2011 online professional development course through the EECapacity project at Cornell University. Plans include Ecological Identity; Restoring Earth, Reflecting on Stories; Marine Ecosystem Invention; and more.

http://urbanee.files.wordpress.com/2011/11/26-lesson-plans.pdf

10. World Network of Indigenous and Local Community Land and Sea Managers

The WIN (World Network of Indigenous and Local Community Land and Sea Managers) is a network that brings together indigenous and local community land and sea managers to share their knowledge and practices in managing ecosystems, protecting the environment, and supporting sustainable livelihoods. Check out the resources, read the stories, and more.

www.winlsm.net

11. Measuring Environmental Education Outcomes

11. Measuring Environmental Education Outcomes

Edited by Alex Russ.

In this e-book, 20 environmental educators across the U.S. are trying to offer a fresh look at environmental education outcomes and their measurement. E-book chapters address such questions as: What counts as outcomes of environmental education? How can their measurement be part of environmental education curricula? How to monitor long-term impacts of environmental education programs? The e-book is prepared for environmental educators and program evaluators. ISBN 978-0-615-98351-6

by editor | Jun 24, 2014 | K-12 Classroom Resources

First graders at St. John the Baptist School observe the beautiful flowers that have developed from the seedlings they planted a year ago

Gardens Grow Minds: The School as Green Educator

by Mary Quattlebaum

“We have a garden! With flowers and butterflies!” The third graders beam as they describe their wildlife garden during my author visit to St. John the Baptist (SJB) School in Maryland.

I thought about their enthusiasm and the dedicated teachers and parent volunteer, Mary Phillips, I met that day as I researched and wrote Jo MacDonald Had a Garden. How best to convey a child’s joy in digging and planting while offering teachers and parents helpful information on starting and/or teaching with a school or backyard garden?

These days, schools, such as SJB, can be the venues best positioned for nurturing a child’s wonder in the natural world. I grew up with a dad who shared his curiosity about nature with his seven kids and umpteen grandkids and showed us how to garden. (He’s the model for Old MacDonald, Jo’s grandfather, in my book, which is an eco-friendly riff on the popular song “Old MacDonald Had a Farm.”)

These days, schools, such as SJB, can be the venues best positioned for nurturing a child’s wonder in the natural world. I grew up with a dad who shared his curiosity about nature with his seven kids and umpteen grandkids and showed us how to garden. (He’s the model for Old MacDonald, Jo’s grandfather, in my book, which is an eco-friendly riff on the popular song “Old MacDonald Had a Farm.”)

But in today’s fast-paced, busy world and with diminishing green spaces, these “growing experiences” and “life lessons” may be missing from childhood.

Happily, SJB seems to be part of a national trend, with an increasing number of schools adding an “outdoor classroom” to the traditional learning environment. At the National Wildlife Federation (NWF), Senior Coordinator Nicole Rousmaniere, who manages school programs, shared recent statistics. More than 4200 schools have started schoolyard habitats that help sustain regional wildlife, she says, with an additional 300 to 400 being added yearly.

Rousmaniere emphasizes that commitment rather than size is the key to an effective “green education” from school gardens. Small can be powerful. Having children plant and care for native plants in containers or in a little patch beside a school can foster lessons in biology and stewardship. Indoor “green” activities pique youngsters’ interest in learning and doing even more. (Dawn has such activities online and in the back of all its children’s books, including Jo MacDonald Had a Garden.)

“Kids love a garden, but you’ve got to start them young,” says William Moss, a master gardener and horticultural educator. Advocating for school and small-space gardening, Moss writes the popular “Moss in the City” blog for the National Gardening Association, hosts HGTV’s “Dig In” and is a greening contributor to “The Early Show” on CBS.

Just about any subject can be taught through a garden, says Moss, including science, math, natural history, geography, nutrition, reading and writing.

A garden offers hands-on and experiential learning, says Phillips, the parent volunteer who helped SJB’s science teacher to create the school garden three years ago. Phillips has seen teachers use the garden to teach units on pollination, history, the food chain and the ozone. Her blog www.theabundantbackyard.com showcases student art inspired by the garden and by the art teacher’s lessons on Georgia O’Keefe’s flower paintings. An added bonus, says Phillips, is that the garden, in addition to enriching academic studies and creative expression, also stimulates the brain, enhances sensory awareness and gets kids outdoors for some exercise.

I thought of all these points so beautifully articulated by Moss, Phillips and Rousmaniere as I researched and wrote Jo MacDonald Had a Garden. My hope, along with illustrator Laura Bryant’s, was not only to playfully introduce youngsters to wiggling worms, fluttering birds and growing plants but to make it easy for teachers and parents to build on basic lessons.

School gardens can be the start of a learning experience that grows over a lifetime. As NWF’s Rousmaniere points out, just as schools teach the 3 R’s, so, too, they might provide a setting that connects children with and increases their knowledge about the natural world. One of the most important lessons to learn young is stewardship, says Rousmaniere, the idea that we are all caretakers of the earth and its wild inhabitants.

Resources for Starting and Learning from a School Garden

William Moss, horticultural educator www.wemoss.org

National Gardening Association www.kidsgardening.org

National Wildlife Federation www.nwf.org

Mary Phillips, school garden advocate www.theabundantbackyard.com

Mary Quattlebaum is the author of Jo MacDonald Had a Garden and numerous other children’s books. She and her family enjoy watching the birds, bugs and other wild creatures that visit their urban backyard habitat. www.maryquattlebaum.com

by editor | Jun 12, 2014 | K-12 Classroom Resources

Middle School Students Use Historic Snowpack Data to Gain Inquiry, Graphing and Analysis Experience

by Joe Cameron

Beaverton Middle School teacher

NRCS Oregon hydrologists Melissa Webb and Julie Koeberle measure snow on Mt. Hood. Courtesy of USDA.

What do you get when you mix researchers, teachers, authentic science opportunities and a group of GREAT people? You get three summers of intense work, reinvigorated teachers, new ideas for the classroom and lots of fun!

For the last three summers I was lucky enough to be involved in the Oregon Natural Resource Education Program’s (ONREP) Climate Change Institute where teachers are matched with researchers to bridge the gap between the classroom and field research. The last two years I worked with Oregon State University’s Dr. Anne Nolin and Travis Roth examining snow pack changes in the McKenzie River Watershed. Investigating snow collection sites and collecting data led to discussions on how best to get students involved in authentic research and science inquiry investigations.

Handout for activity below.

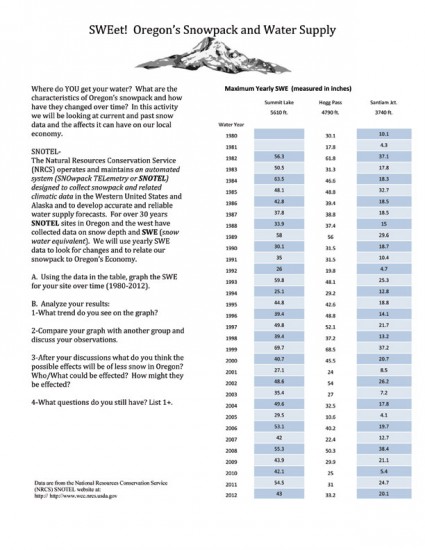

One of my goals for the year was to get my students involved in authentic data collection and to gain more experience and practice in graphing. From this, SWEet! was born. SWEet is an activity that engages students in using historic snow data to investigate the SWE, or Snow Water Equivalent, and the changes taking place in the Cascade Mountains in Oregon. Students graph and analyze data from SNOTEL sites and compare their findings with others in class to make predictions about future snowpack. In extension activities students choose their own SNOTEL sites in the Western U.S. and monitor snow data monthly throughout the snow year. This type of activity will in turn introduce students to long-term ecological studies in progress and support them to begin studies of their own.

In doing this activity with my students we first investigated their particular sites. I found this helped them personalize the data and they were very involved, especially using this “local” data. Then using their data they were able to create comparative line graphs and look for trends in the data, even with a complex and varied data set. These trends were then used to hypothesize possible effects of changes in the snowpack to their world and the economy and ecosystems found in Oregon.

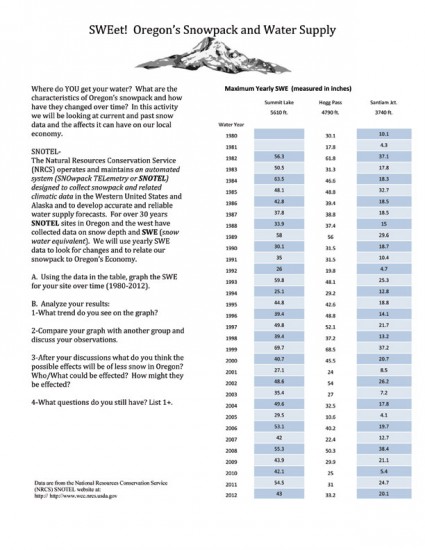

SWEet! Oregon’s Snowpack and Water Supply

Author: Joe Cameron

Time: 50+ minutes

Grade Level: 6-12

Background

SNOTEL-The Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) operates and maintains an automated system (SNOwpack TELemetry or SNOTEL) designed to collect snowpack and related climatic data in the Western United States and Alaska in order to develop accurate and reliable water supply forecasts. For over 30 years, data on snow depth and SWE (Snow Water Equivalent) have been collected from SNOTEL sites throughout the western US. This activity will use yearly SWE data from three SNOTEL sites in Oregon to look for changes and relate our snowpack to Oregon’s economy and environment.

Introduction

Familiarize students with Snow Water Equivalent (SWE), which is the amount of water contained in the snowpack. A simple reference for background information is http://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/detail/or/snow/?cid=nrcs142p2_046155. Also, you can do a simple class demonstration by taking a 500ml beaker of snow (or blended ice) and melting it using a hot plate. I have students predict how much water will remain after the ‘snow’ is melted. Then, we calculate the percent water in the snow to give them an example of one way to analyze this type of data.

After getting the students comfortable with SWE, you can give them the SWEet! Oregon’s Snowpack and Water Supply activity page. When I led this activity, we read through the introduction as a class and then directed the students to graph the data provided, make sense of their plot, compare their results with others in class and then draw conclusions. This lesson leads to discussions of our changing climate and possible changes in store for the people, plants and animals of Oregon.

Objectives

Students will access long term ecological data.

Students will graph SWE data.

Students will compare their data with data from their classmates.

Students will identify possible effects of a decrease in snowpack.

Vocabulary

SWE-Snow Water Equivalent; the amount of water found in snow.

SNOTEL-automated system that records snow depth and related data in the western United States

Trend-a general direction that something is changing

Snowpack-the amount of snow that is found on the ground in the mountains; usually measured at specific sites.

Standards

Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS)

MS-ESS2-5. Collect data to provide evidence for how the motions and complex interactions of air masses results in changes in weather.

MS-ESS3-5. Ask questions to clarify evidence of the factors that have caused the rise in global temperatures over the past century.

Oregon Science Standards

Scientific Inquiry: Scientific inquiry is the investigation of the natural world based on observations and science principles that includes proposing questions or hypotheses, designing procedures for questioning, collecting, analyzing, and interpreting multiple forms of accurate and relevant data to produce justifiable evidence-based explanations.

Interaction and Change: The related parts within a system interact and change.

6.2E.1 Explain the water cycle and the relationship to landforms and weather.

7.2E.2 Describe the composition of Earth’s atmosphere, how it has changed over time, and implications for the future.

7.2E.3 Evaluate natural processes and human activities that affect global environmental change and suggest and evaluate possible solutions to problems.

8.2E.3 Explain the causes of patterns of atmospheric and oceanic movement and the effects on weather and climate.

8.2E.4 Analyze evidence for geologic, climatic, environmental, and life form changes over time.

Materials

For Demonstration:

1 500 ml beaker

1 50-100 ml graduated cylinder snow OR chopped/blended ice

1 hot plate

For Activity:

Copies of SWEet! Oregon’s Snowpack and Water Supply activity page

Graph paper

Optional: colored pencils/pens

Lesson Procedure

1. Give students the SWEet! Activity page.

2. As a class, read and review all directions.

3. Students may choose 1, 2, or 3 sets of data to graph. This option allows the activity to be modified to meet the individual students’ abilities. Also, students can create graphs that can be compared to multiple data sets.

4. Students graph the data in a line graph.

5. Students analyze the data. This part can be completed through drawing a trend line(s) on the graph, calculating averages, adding totals and/or comparing multiple data sets looking for similarities and differences. Note: having the students do their graphing using Excel spreadsheets is an option that is not always available in our school but from which the students would benefit.

6. Relate the observed trends in snowpack to possible effects in Oregon. Who/What will be affected? How will/might they be affected?

7. Students pose one other question OR concern they have after looking at their graphs and trends for possible additional exploration.

Extensions

1-Related current event articles from Science Daily:

Warming Climate Is Affecting Cascades Snowpack In Pacific Northwest

Found at http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/05/090512153335.htm

Global Warming to Cut Snow Water Storage 56 Percent in Oregon Watershed

Found at http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2013/07/130726092431.htm

2-Students can access current snow year data online. They go to SNOTEL website, choose a specific site and collect daily, weekly or monthly data for this site throughout the winter months (the snow year stretches from November to March). Students can also access historic data going back to the late 1970’s and early 1980’s for their sites.

References Science expertise was provided by the following Oregon State University Faculty: Dr. Anne Nolin – Professor and Travis Roth-Doctoral Student in the College of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Sciences. Data are from the National Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) SNOTEL website at: http://www.wcc.nrcs.usda.gov

Acknowledgements These lessons were created using information learned in the Oregon Natural Resource Education Program’s Researcher Teacher Partnerships: Making Global Climate Change Relevant in the Classroom project. This project was supported by a NASA Innovations in Climate Education award (NNXI0AT82A).

Thanks to Dr. Kari O’Connell with the Oregon Natural Resources Education Program at Oregon State University and Dr. Patricia Morrell in the College of Education at University of Portland for their thoughtful review of this article.

Joe Cameron is a teacher at Beaverton Middle School in Beaverton, Oregon. He can be contacted at joe_cameron@beaverton.k12.or.us