by editor | Jan 21, 2015 | Place-based Education, Questioning strategies

Were You Assigned A Class You Have No Background or Preparation to Teach?

by Jim Martin

CLEARING Associate Editor

ne year, I worked with a middle-school mathematics teacher who decided to engage his class in some work on a wetland and lake bordering a large river. He did this partly as a diversion from classroom struggles – his background and training weren’t in middle school mathematics; there was no one else available to do the work. And, he was interested in the concept of engaging his students in their community – project-based learning.

ne year, I worked with a middle-school mathematics teacher who decided to engage his class in some work on a wetland and lake bordering a large river. He did this partly as a diversion from classroom struggles – his background and training weren’t in middle school mathematics; there was no one else available to do the work. And, he was interested in the concept of engaging his students in their community – project-based learning.

So, we went down to the site and took a tour. As we walked and talked, he suddenly stopped, took a few steps back, and stood looking down a shallow slope to the lake, then up the slope toward a wooded copse. I waited a few moments, then he remarked in an excited voice that everything changed as you looked from the water to the slope, and on up to the trees. He said something made that change, and it had to do with the slope. Then, he described what students would explore on a transect along the slope, and how. Wow! His class did the project, and, within two years, he developed into a very effective teacher.

What happened here? He knew he wanted to do something. He knew where he was in his mathematics teaching. And he was interested in his students. But he didn’t get any further until he took a walk, talked about what was there and what students had done, and noticed a slope – geological and mathematical – and, in terms of subsequent progress as a teacher, clarivoyant. The pieces of the puzzle suddenly came together.

How do we move from teaching our curricula one piece at a time, a disconnected clutter of disparate parts? Parts, learned long enough to refer to in a test; then, lost in a long trail of discarded artifacts. We need clear, strong trails if we are to lead effective, self-actualized lives. Learning has the potential to help us organize our selves so that our lives produce clear, permanent trails. In his teaching the middle school mathematics teacher began to build these clear trails, both for himself, and for his students. Part of the secret is learning about the curriculum in the real world, and its connection to the disparate clutter of artifacts we teach. In the classroom and on environmental education sites. I suggest we need to integrate them.

One thing this teacher did was to let the class in on the plan. Doing this at the start involved and invested them in the work, and began to empower them to take responsibility for its parts. Early on, he began to notice that students were doing good work, and that they brought different sets of skills and abilities to the work. This was a pleasant surprise for him, and he began to see the class as a group of individuals who could make the classroom work environment an interesting one to be part of.

One thing this teacher did was to let the class in on the plan. Doing this at the start involved and invested them in the work, and began to empower them to take responsibility for its parts. Early on, he began to notice that students were doing good work, and that they brought different sets of skills and abilities to the work. This was a pleasant surprise for him, and he began to see the class as a group of individuals who could make the classroom work environment an interesting one to be part of.

Soon enough, he reorganized the class into work crews, each one responsible for part of the job of assessing a transect up the slope from water’s edge to wooded copse. Accomplishing this was an utterly new experience for him, but he took to it as if he’d done it for years. Within a few weeks, he was beginning to coordinate his curriculum to the work on the slope. Aware of the mathematics curricula he was charged with, he organized the school week into days dedicated to mathematics and to the project. Students didn’t divide their new sense of personal investment in school. They became reliable students each day. Why? I think, because they were learning as humans evolved to learn. How their brain is best organized to do that job. Go into the real world, find real work to do, then focus all resources on this.

I think there were several vehicles which enabled this classroom to navigate from struggling to self-powered learning place. Specifics varied among teacher and students, but each vehicle carried them through its part of the course. The teacher was charged with teaching mathematics, for which he wasn’t well-prepared to do. He was both interested in improving his teaching, and in engaging his students in learning projects in the community in which they lived. Then he saw something, a slope in a landform, that brought these two seemingly disparate entities into a dynamic construct, a conceptual foundation for real learning, learning for understanding.

His students also boarded their first vehicles: crews, embedded curricula, brain work. At first, their commitment varied, but nearly all became interested in the project when they heard about it from the teacher. At the beginning, they were randomly assigned to their groups; but, as the teacher became more aware of them as individuals, he began to reorganize them into effective working groups, crews organized to execute particular parts of the plan.

So, the relationships among the people in the class began to morph. The teacher became the project manager, and the crews became technicians and staff working with a crew leader. Project manager and crews learned to reach out to local experts for advice. The teacher, because he was managing the project, and feeling responsible for teaching mathematics, began to use the mathematics embedded in the work site and the work itself to deliver part of his curriculum.

Locating embedded curricula seems difficult at first thought, but once you try, it becomes relatively easy. For instance, students can measure the maximum width and length of a leaf, and calculate the width to length ratio. They repeat this with other leaves from the same tree to see if that ratio holds true. Then they can see if there is a ratio for the maximum width of a fir or pine cone and its length that is consistent among a sample from the same species. As they do, ratio and proportion becomes sensible, a conceptual tool to use, rather than something to memorize for a test.

This doesn’t apply just to mathematics and science. Look for examples of alliteration in a natural area or in the school’s neighborhood. I’m looking at an example just now – a small tree whose leaves are attached to thin branches in an alternating sequence. When I see a set silhouetted against the sky, their leaves tripping along the branch, I see alliteration. Looking out the same window, I see many metaphors. Metaphors which can activate the same parts of my brain that are activated when I am engaged in close pursuit of the answer to an inquiry question. A very useful brain tool.

Looking past the leaves and metaphors, I see examples of social studies, music, art, drama, history. It’s all out there, the curricula we teach, in a form our brain is organized to use. Once it is engaged, we can then move into the prepared curricula which lives in classrooms. With one difference – this curricula will come to life because it will be engaged by a need-to-know generated by the world we live in. And learned in a way that ensures it will be used. In time, you will find that you can milk the prizes found on one excursion from the classroom to the schoolground, neighborhood, or riparian area for more than the embedded curricula you find. What you find and use generally has links to other curricula, and you can extend these threads quite far before you’ve either used them up, or have become tired of them.

These are things the teacher I worked with learned during the time we explored learning for understanding. By moving into the world we live in and discovering the curricula embedded there, and the involvement and investment the experience invoked in his students, he began to reorganize his teaching. The mathematics he discovered on site clarified what he was trying to teach in the classroom. The energy and growing expertise his students brought to the work helped him learn them as persons, to know when they engaged what I call the moment of learning, and to use their individual strengths to overcome their weaknesses. And they all grew. Because, in my opinion, they engaged their brains in the way brains evolved to learn and cope. Once engaged, they were ready to enter the more formal, abstract curricula which lived in their classroom. To learn it, not to pass a test, but to build their lives.

This is a regular feature by CLEARING “master teacher” Jim Martin that explores how environmental educators can help classroom teachers get away from the pressure to teach to the standardized tests,and how teachers can gain the confidence to go into the world outside of their classrooms for a substantial piece of their curricula. See the other installments here, or search Categories for “Jim Martin.”

This is a regular feature by CLEARING “master teacher” Jim Martin that explores how environmental educators can help classroom teachers get away from the pressure to teach to the standardized tests,and how teachers can gain the confidence to go into the world outside of their classrooms for a substantial piece of their curricula. See the other installments here, or search Categories for “Jim Martin.”

by editor | Dec 18, 2014 | Place-based Education

Phenology Wheels: Earth Observation Where You Live

By Anne Forbes, Partners in Place, LLC

By Anne Forbes, Partners in Place, LLC

This article originally appeared in Earthzine – http://earthzine.org/

.

.

aking a habit of Earth observation where you live is a fun and fundamental way to practice Earth stewardship. It is often our own observations close to home that keep us inspired to learn more and allow us to remain steady advocates for solutions to today’s daunting problems. Earth observation done whole-heartedly becomes skilled Earth awareness that leads to profound relationships with the plants, animals, and seasonal cycles surrounding us in real time, whether we live in the city, suburbs, or countryside.

aking a habit of Earth observation where you live is a fun and fundamental way to practice Earth stewardship. It is often our own observations close to home that keep us inspired to learn more and allow us to remain steady advocates for solutions to today’s daunting problems. Earth observation done whole-heartedly becomes skilled Earth awareness that leads to profound relationships with the plants, animals, and seasonal cycles surrounding us in real time, whether we live in the city, suburbs, or countryside.

Courtesy Anne Forbes.

One way to track Earth observations is an activity called Phenology Wheels, suitable for individuals, families, classrooms, youth programs, and workshops for people of all ages. Phenology is a term that refers to the observation of the life cycles and habits of plants and animals as they respond to the seasons, weather, and climate. A Phenology Wheel is a circular journal or calendar that encourages a routine of Earth observation where you live. Single observations of what is happening in the lives of plants and animals made over time begin to tell a compelling story – your story – about the place on our living planet that you call home.

Why a circle? We usually think of the passing of time as linear, with one event following another in sequence by day, by month, by year. Placing the same events in a circular journal, or wheel shape, helps us discover new patterns (or rediscover known ones). We can use the Phenology Wheel to communicate about what is really important or interesting to us.

Here’s the General Idea

A Phenology Wheel is made up of three rings in a circle, like a target. To become a Wheel-keeper, you select a home place, such as a garden, a “sit spot,” schoolyard, watershed, or landscape that will be represented by a map or image in the center ring, the bull’s eye. Next, you mark units of time – such as the months and seasons of a year, hours of a day, or phases of a lunar month – around the outside ring, like the numbers on the face of a clock. Then, as you make specific observations of what is going on in the lives of plants and animals and the flow of seasons, you record them within the middle ring using words, phrases, images, or a combination.

Here’s How To Get Started

Because the wheel is round, you can begin a Phenology Wheel for Earth observation at any time of year.

Although you can pick among different time scales for the outer ring, let’s begin here with a year of seasons and months.

Courtesy Anne Forbes.

1. Draw a set of nested circles on a large piece of paper. You can do this by tracing around large plates or pizza pans, by using an artist’s compass or by making your own compass out of a pencil, pin, and string. You may also purchase a kit of print Wheels or a set of digital PDF Wheels online.

2. If you are making your own Wheel, write the names of the seasons and months on the outer rings.

3. Select an image for the center to represent the place or theme you have selected and to anchor your practice of observation in time and space.

Maps for the Center: If you choose a map, will it be geographically accurate or symbolic? Will it be traced or cut and pasted from an existing map, or will it be a map of your own creation?

Tip: Use a web-based mapping system such as Google Maps to print a map and use it to trace selected features as a base map for your Wheel.

A Centering Image: If you choose an image other than a map, will you create your own image or use one that you find already in print material? Will you use a photo, make a collage, or choose a found object, like a leaf or feather?

Tip: Children often enjoy a picture of themselves at their “sit spot” or other place they have chosen to track their observations.

4. Establish a Routine: Observe → Investigate and Reflect → Record

OBSERVE: What do I notice in this moment? What is extraordinary about seemingly ordinary things? What surprises me as unexpected or dramatic?

then

INVESTIGATE: What more do I want to know about what I observe? What questions will I seek to answer through my own continued observation? What information will I search for in books or from mentors or websites?

and

REFLECT: What does my observation mean to me? How is it changing me? How does it help me explore my values and beliefs?

then

RECORD: A routine of frequent observation provides the raw material to transform your blank Wheel into a circular journal as you record images, symbols, or words as you observe the passing of the seasons in your home place.

Tip: An interactive diagram of this process can be found under the Observe & Record tab here.

5. Share and Celebrate: Use your Wheel to report or tell stories about what you learn from and value about Earth observation in your home place.

Like a wheel on a cart, time turns around the hub of your home place;

the metaphor is a journey taken through a day, a month, a year,

or a lifetime of curiosity and appreciation.

Of course, you don’t have to keep a journal to explore and appreciate your home place on earth and the home place in your heart. What are the dimensions of your home place in this moment? What marks of time’s passing do you observe? The more playful you are with these questions, the more you may feel a part of your home place and committed to co-creating its well-being with others in your community.

Courtesy The Yahara Watershed Journal.

Welcome home.

Example #1: The Yahara Watershed Wheel

About twelve years ago, a group of like-minded friends gathered by my fireside to reflect upon what it means to live in this place we call home in Dane County, Wisconsin, USA. We chose to think of the Yahara Watershed as our common home place, and the series of seasonal events that occur in a typical year as the time scale to track. We put a map of the watershed in the center of a large Wheel of the Year, with units of time going around the outside rim, much like a clock, but using seasons and months instead of hours. We then went around our own circle, each speaking of the defining moments in the natural world and in the lives of people enjoying it throughout the months of a typical year. The artist among us sketched the images onto the Yahara Watershed Wheel that you see here. The detail in the enlarged image represents the unique happenings in March and April: pasque flowers in bloom, the return of redwing blackbirds and sandhill cranes, woodcock mating dances, first dandelions, and spring peepers in chorus.

Courtesy Anne Forbes.

Example #2: Poems of Place

In reporting on this Wheel filled with seasonal poems by 4th and 5th graders about the large school woods, just outside an elementary school “backdoor” in Cambridge, Wisconsin, teacher Georgia Gomez-Ibanez writes, “Because the woods is so accessible, the children spend quite a lot of time there developing a deep sense of place, including keen observational skills and a heightened imagination, all enhanced by the affection they have gained by years of exploring, learning and stewardship.” This selection of student poems illustrates how Phenology Wheels can be used to enhance language arts as well as science curriculum.

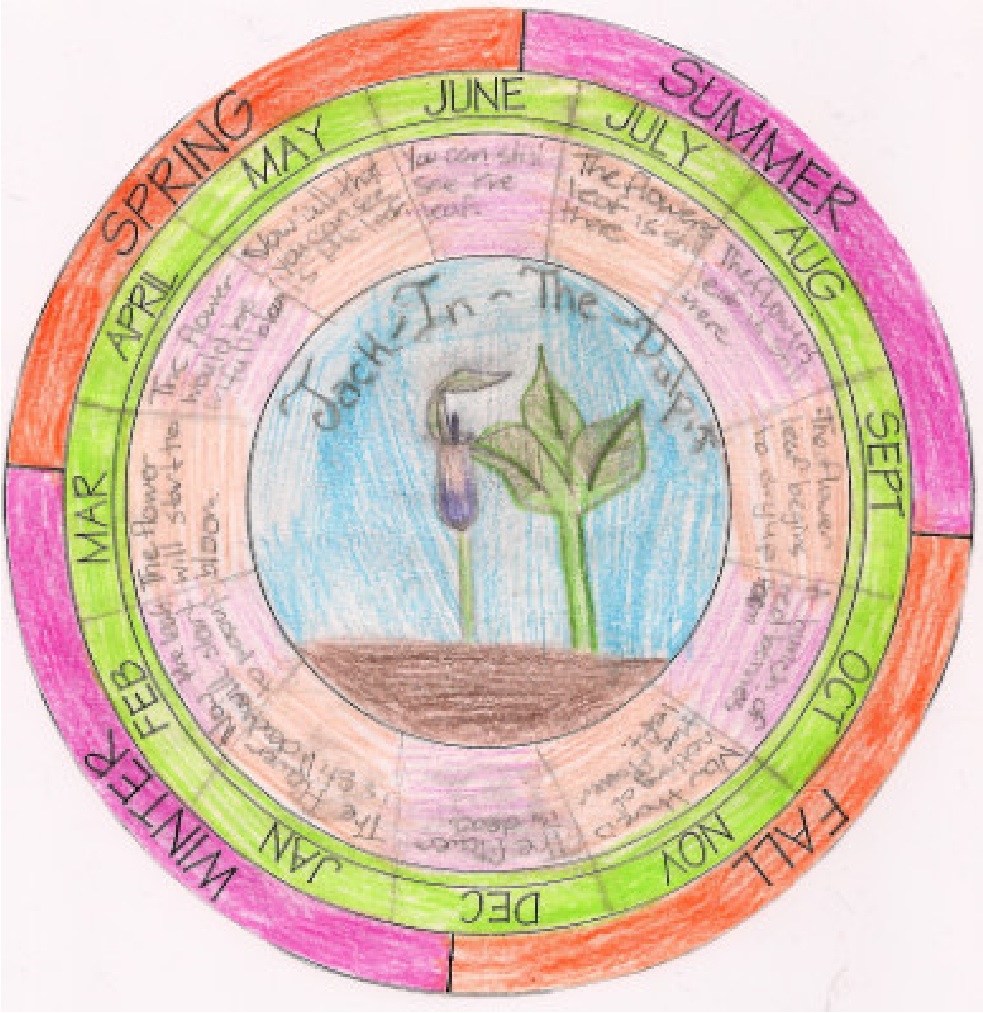

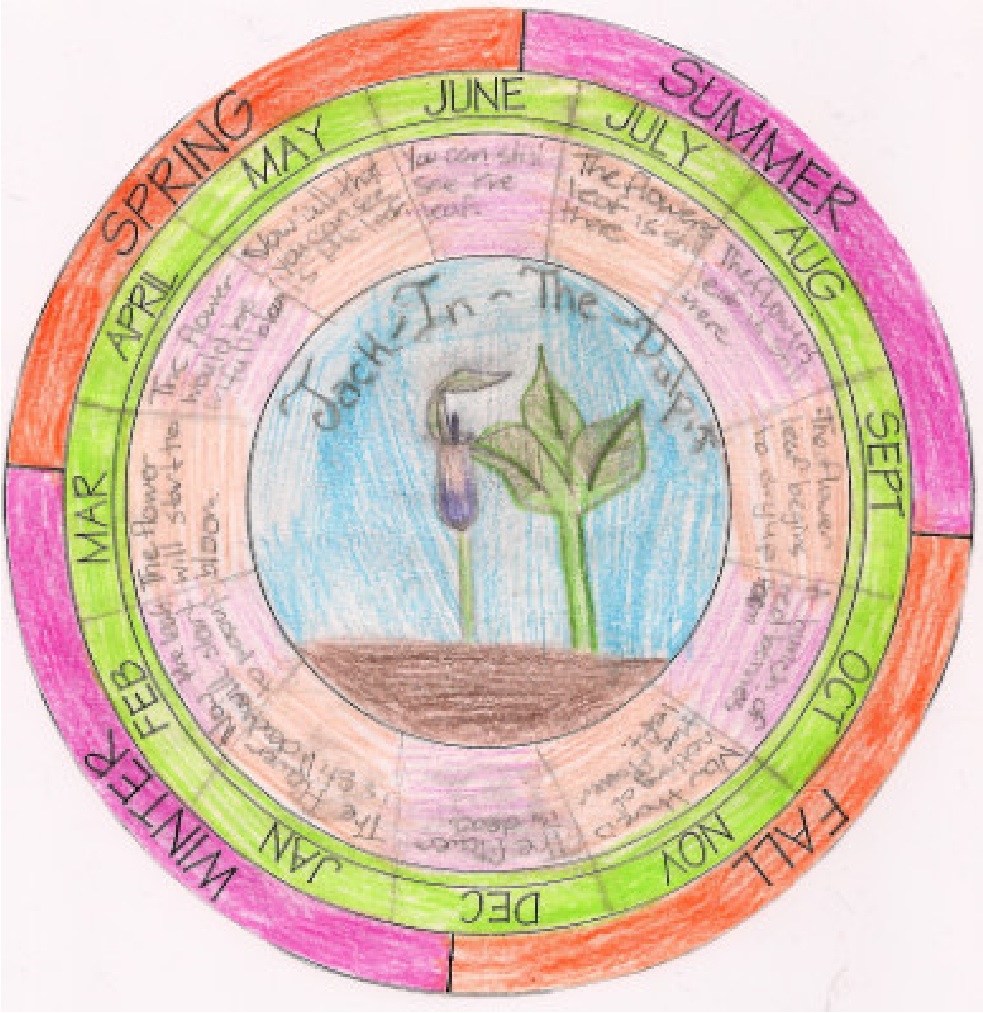

Example #3: Local Biodiversity

In another example from Cambridge Elementary School in Wisconsin, teacher Georgia Gomez-Ibanez reports that a classroom studied the biodiversity of the area where they live. Each student picked a different animal or plant from their adjacent woods or prairie for the center of an 11-inch Wheel and then did research to tell the full story of the life cycle in words. The example here shows the work of one student who studied the Jack-in-the-Pulpit wildflower.

The next step would be for the students to combine their information for single species onto one large 32-inch Wheel and use it to explore the dynamics of the ecosystem that appear through food webs, habitat use, seed dispersal mechanisms, and so on.

Frequently Asked Questions

Courtesy Anne Forbes.

1. Where do I get more information?

If you are ready to start a Phenology Wheel for yourself, family, classroom or youth program, or any other interest group:

• Visit the Wheels of Time and Place website for instructions, resources, and a gallery of examples.

• Download a curriculum for youth developed in partnership with Georgia Gomez-Ibanez, an elementary school teacher, and Cheryl Bauer-Armstrong, Earth Partnership for Schools, UW-Madison Arboretum.

2. Where do I order pre-made Wheels?

Order the blank Wheel templates as a digital download of PDF files or as a complete toolkit, Wheels of Time and Place: Journals for the Cycles and Seasons of Life. The latter includes a set of print Wheels in 11-inch and 24-inch sizes, a code to download the PDF files, and an instruction booklet – all in a recycled chipboard carrying case.

3. What size should my Wheels be?

Some people prefer 11-inch Wheels because they are compact, portable, and can be easily duplicated in a copy machine on 11 x 17-inch paper. You can trim them down to 11-inch square if you would like.

When people share the 24-inch Wheels, their faces often light up with excitement. This size, or larger, works well if you have a large clip board or a place to keep it posted for frequent use or when people are working on one Wheel in a group.

Of course, if you make your Wheels by hand, you can make them any size you like. If you purchase the PDF files, you can enlarge them up to 32-36 inches at a copy or blueprint shop.

4. What if I’m already a journal-keeper?

Some people who already keep a written journal use the Wheels to review their journals periodically and pull out observations to further explore and put on a Wheel. It’s amazing what patterns and stories can emerge.

5. Can the Wheels be created from databases?

Frank Nelson of the Missouri Department of Conservation has used wheels called Ring Maps, A Useful Way to Visualize Temporal Data to show trends and reveal patterns in a complex set of data.

________________________________

Anne Forbes of Partners in Place, LLC is an ecologist who seeks to integrate her scientific and spiritual ways of knowing. For over 35 years, she worked on biodiversity policy as a natural resource manager and supported environmental and community collaborations as a facilitator and consultant. Her years of spiritual practice in varied traditions, most recently the Bon Buddhist tradition of Tibet, inspire her commitment to engaged action on behalf of present and future generations. She failed her first attempt at retirement and instead created the Wheels of Time and Place: Journals for the Cycles and Seasons of Life.

Contact: anne@partnersinplace.com.

by editor | Oct 13, 2014 | Place-based Education, Service learning

To view this article in .pdf format, click here: MyMcKenzie

An environmental education professional development program using

place-based service-learning

by Kathryn Lynch

University of Oregon Environmental Leadership Program

here does your drinking water come from? It is a simple question, and given that humans can survive only a few days without water, a critical one. Yet, too many people cannot answer this most basic question. In Eugene, this lack of connection is often compounded by the transient nature of a large sector of the population (university students) who are often just passing through on their way to careers elsewhere.

here does your drinking water come from? It is a simple question, and given that humans can survive only a few days without water, a critical one. Yet, too many people cannot answer this most basic question. In Eugene, this lack of connection is often compounded by the transient nature of a large sector of the population (university students) who are often just passing through on their way to careers elsewhere.

To respond to this serious disconnect with nature, the Environmental Leadership Program (ELP) launched a set of new EE projects in 2012 focused on helping students develop a connection to the sole source of their drinking water, the McKenzie River. This stunning 90-mile long river provides many gifts: clean drinking water, fish and wildlife habitat, recreation, hydropower, and inspiration. The watershed offers fascinating and complex geology and geomorphology, multi-faceted and controversial land use issues, and a strong sense of community and history tied to place. Many organizations are doing work in the watershed, which provides opportunities for students to directly engage in conservation issues. In sum, the watershed provides a great laboratory for interdisciplinary, place-based education and service learning.

The two main goals of the new EE effort were to: 1) create a year-long program for UO students interested in EE careers (that would provide them with the knowledge, skills and confidence to develop and implement place-based, experiential programs) and 2) develop age-appropriate, engaging MyMcKenzie curricula for local youth, grades 1-8, that promotes the stewardship of the McKenzie River.

The two main goals of the new EE effort were to: 1) create a year-long program for UO students interested in EE careers (that would provide them with the knowledge, skills and confidence to develop and implement place-based, experiential programs) and 2) develop age-appropriate, engaging MyMcKenzie curricula for local youth, grades 1-8, that promotes the stewardship of the McKenzie River.

To prepare the undergraduates for their service projects, we offered a new fall course called Understanding Place: the McKenzie Watershed. The goal was to provide the necessary foundation for them to become effective place-based educators. During the 10-week course, we examined the geological, ecological, historical, social, and political influences that shape the McKenzie watershed. Six field trips took us from the headwaters to the confluence, where we explored lava flows, springs, hiking trails, dams, hatcheries, restoration projects, historical sites and more. Guest speakers provided diverse perspectives on Kalapuya culture, salmon restoration, water quality and management, and sustainable agriculture, among other topics. We wanted students to hear directly from the farmers, anglers, residents, scientists, policymakers and regulatory agencies that shape the watershed’s past, present, and future. Through diverse hands-on, student-led activities, the class gained a spatial and temporal understanding of the McKenzie, and contemplated the meaning of “place,” what contributes to a sense of place, and how it influences people’s worldviews and choices.

In the subsequent winter course, Environmental Education in Theory & Practice, UO students learned how to transform their new knowledge of the McKenzie River into engaging place-based educational programs. Participants gained a working knowledge of best practices in EE through readings, guest lectures, field trips, and most importantly, their service-learning project in which they developed educational materials for their community partners. The “Critters and Currents” team worked in partnership with Adams Elementary School to develop two classroom lessons and one field trip for each grade level. The “Canopy Connections” team developed and facilitated field trips for middle-schoolers that included a canopy climb, building watershed models, and mapping, among other activities. All the activities used the McKenzie River as the integrating context, and placed particular emphasis on systems thinking, and how the health of the river directly affects us, as the river provides our drinking water.

While the specifics of the curricula were left up to the teams to determine, all teams were required to: 1) incorporate an interdisciplinary approach, 2) include multicultural perspectives, 3) use experiential, inquiry-based methods, 4) promote civic engagement, and 5) articulate assessment strategies. Their materials were pilot-tested at the end of winter term, and then the teams worked with their community partners to implement their EE programs throughout spring term. Each UO student completed approximately 120 hours of service, which entailed facilitating field trips, classroom visits and developing supplemental educational materials (e.g. websites, presentations). What follows next are descriptions of the two 2013-2014 projects, written by the team members themselves.

Case Study 1:

Case Study 1:

Critters and Currents

By Leilani Aldana, Leah Greenspan, Courtney Jarvis, Claire Mallen, Anna Morgan, Trevor Norman, Makenzie Shepherd, Tony Spiroski, Britney VanCitters, Cheyenne Whisenhunt, Alicia Kirsten (graduate project manager).

iking along the McKenzie River trail is unlike anything else in its breathtaking beauty and awe. The trees tower above, the firs paint the horizon green, and the moss blankets the forest floor. Squirrels dart back and forth, winged insects buzz through the misty air, and regal ospreys circle above the river, spying on possible prey below. All these organisms work together in the carefully orchestrated equilibrium that is a Pacific Northwest forest. And although the forest can be serene, delicate, and quiet, it also tells a bold and enduring story to those who are willing to listen and fortunate enough to hear.

iking along the McKenzie River trail is unlike anything else in its breathtaking beauty and awe. The trees tower above, the firs paint the horizon green, and the moss blankets the forest floor. Squirrels dart back and forth, winged insects buzz through the misty air, and regal ospreys circle above the river, spying on possible prey below. All these organisms work together in the carefully orchestrated equilibrium that is a Pacific Northwest forest. And although the forest can be serene, delicate, and quiet, it also tells a bold and enduring story to those who are willing to listen and fortunate enough to hear.

The forest’s tale is told by the many plants, fungi, animals, and humans that call it home. At one point, the entire McKenzie watershed told this story; the indigenous Kalapuya and Molalla people lived closely with their varied and unique plant and animal neighbors, constructing a narrative out of the reciprocity that encouraged a long-lasting relationship. Eventually the plot of this story was thrust in another direction, as the influx of newcomers would alter the face of this territory through extensive land management techniques and exploitation of natural resources. Today, the story of the McKenzie River watershed illustrates the growing disconnection between forests and our society brought by global urbanization. But the story is not yet over, and we have the unique opportunity to transform it.

The prominence of technology and urbanization in the 21st century has established an obvious distinction between the urban and natural worlds. Younger generations, increasingly disengaged and separated from their local natural environments, exhibit symptoms of what is colloquially called “nature-deficit disorder” (Louv 2008). Marked by rising levels of ADD/ADHD, obesity, depression, and muted creativity, nature-deficit disorder will accelerate if not immediately and holistically addressed.

Nature has the ability to inspire us, teach us, and transform our lives. By giving children the chance to explore the natural world, we allow them to experience the story nature has to tell. Utilizing place-based lessons and hands-on activities, environmental education helps students gain an ecological awareness and an understanding of natural processes. Infusing curricula with environmental themes and concepts has proven to foster stewardship and improve support for conservation (Jacobson 2006).Communities need to work collaboratively to ensure that children are provided with the awareness, knowledge, attitudes, and skills necessary to tackle future environmental problems. As environmental educators, we have enthusiastically decided to face this task; we are working to encourage deep and meaningful connections between students and nature, with the goal of nurturing responsible and active citizens.

The 2014 Critters and Currents team worked to help students connect to and build kinship with the McKenzie watershed.Our team of ten undergraduate students and project manager collaborated for six months with Adams Elementary School to bring children to visit the Delta Old-Growth Forest, the H.J. Andrews Experimental Forest, and Green Island which is managed by the McKenzie River Trust. We created curricula that promotes environmental awareness, inspires respect and compassion for the natural world, and encourages positive environmental action now and in the future.

Building connections and gaining understanding is crucial to implementing environmental education. David Sobel, whose work focuses on place-based education, states, “If we want children to flourish, to feel truly empowered, let us allow them to love the earth before we ask them to save it.” (Sobel 1996:39). By encouraging children to experience and explore the McKenzie River, students will become empathetic and compassionate toward their local ecosystems.

Throughout the spring, students at Adams Elementary School in Eugene, Oregon were able to participate directly in the narrative of the McKenzie River watershed. By constructing and decorating fabric bird wings that they can wear, our students were able to become the birds that live in the McKenzie River watershed; by developing proper habitats for real life decomposers such as pill bugs, sow bugs, and earthworms, our students were directly responsible for the lives of those who prolong McKenzie River ecosystems; by intimately learning about a particular McKenzie River critter through storytelling and haiku writing, our students became empowered to protect and defend that critter and its home. Providing our students with activities that nourish empathy for the McKenzie River watershed and its inhabitants inspires a sense of love and awe that lasts, like the narrative itself, a lifetime.

As adults, we often overlook the joys of simply being in the natural world. A childlike sense of wonder allows us to tap into long-forgotten natural connections that help foster a symbiotic relationship with nature once again, one that not only takes our breath away but also fills us with life. We stand in awe of the towering pines and vibrant mosses that carpet the old-growth forest floor; we are struck with silence as the wings of the great osprey beat the air above us and the tiny patterns of a water skimmer are drawn across a serene pond. These subtle, yet profound, experiences allow us to narrate our own story about the environment that surrounds us and how we as a community will care for it.

As adults, we often overlook the joys of simply being in the natural world. A childlike sense of wonder allows us to tap into long-forgotten natural connections that help foster a symbiotic relationship with nature once again, one that not only takes our breath away but also fills us with life. We stand in awe of the towering pines and vibrant mosses that carpet the old-growth forest floor; we are struck with silence as the wings of the great osprey beat the air above us and the tiny patterns of a water skimmer are drawn across a serene pond. These subtle, yet profound, experiences allow us to narrate our own story about the environment that surrounds us and how we as a community will care for it.

Let us persist with our place-based environmental education movement, where classrooms shift from hard desks and chalkboards to engaging the senses and producing first-hand experiences; where students can form intimate relationships with the story told by an old-growth forest or the wetlands of a floodplain forest, rather than reading about it in a textbook. Let us begin the shift to the great outdoors, where we can learn from the greatest storyteller of all: nature itself.

Case Study 2:

Canopy Connections

By Justin Arios, Brandon Aye, Jen Beard, Cassie Hahn, Megan Hanson, Tanner Laiche, Hannah Mitchel, Christine Potter, Meghan Quinn, Christy Stumbo, Jenny Crayne (graduate project manager).

he 90-foot tall Douglas-fir swayed gently in the wind. Multiple ropes hung from the top, waiting to be climbed. The students buzzed with excitement and nervousness as Rob and Jason from the Pacific Tree Climbing Institute prepared them to climb. On their own effort, most students ascended to the top of the tree, swaying with the tree and seeing the forest with a bird’s-eye view.

he 90-foot tall Douglas-fir swayed gently in the wind. Multiple ropes hung from the top, waiting to be climbed. The students buzzed with excitement and nervousness as Rob and Jason from the Pacific Tree Climbing Institute prepared them to climb. On their own effort, most students ascended to the top of the tree, swaying with the tree and seeing the forest with a bird’s-eye view.

Canopy Connections 2014 was developed and facilitated by 10 undergraduate students and included a 50-minute pre-trip classroom lesson and an all-day field trip to HJ Andrews Experimental Forest. Through our field trip, we sought to immerse students in nature, foster a connection to place, and teach students about the processes and biology of an old growth forest. Connecting to nature at an early age combats Richard Louv’s theory of “nature-deficit disorder” and instills a culture of respect and awe for the natural world and hopefully, the long-term protection of natural places.

Canopy Connections 2014 was developed and facilitated by 10 undergraduate students and included a 50-minute pre-trip classroom lesson and an all-day field trip to HJ Andrews Experimental Forest. Through our field trip, we sought to immerse students in nature, foster a connection to place, and teach students about the processes and biology of an old growth forest. Connecting to nature at an early age combats Richard Louv’s theory of “nature-deficit disorder” and instills a culture of respect and awe for the natural world and hopefully, the long-term protection of natural places.

We built our field trip around the theme of “Students as Scientists,” integrating both science and the humanities. In addition to ascending into the canopy of a Douglas-fir, participating students collected scientific data, sketched native plant species, creatively expressed their observations through journaling, and built a debris shelter. Each lesson incorporated activities of various disciplines and catered to different learning styles. This rationale is supported by Howard Gardner’s multiple intelligences theory which argues that students learn and process information many different ways. We used this reasoning to construct activities that engaged students’ learning habits via kinesthetic, linguistic, visual, inter- and intrapersonal, naturalist, and logical learning methods.

Our first interaction with the students was during the pre-trip lesson. We built upon their knowledge of geography to construct a map of Oregon, highlighting cities, mountain ranges, and rivers connected with the McKenzie River. At Fern Ridge Middle School, the students were eager to add other features to the map as well, including the Long Tom, the small river flowing behind their school. Once complete, half the class was given a term relevant to the field trip such as “geomorphic” and “species richness” while the other half was given definitions. The students mingled in the class, helping each other to match the terms with the definitions.

On the morning of their field trip, the students arrived at HJ Andrews, armed with the knowledge gained from the pre-trip lesson. As they filed off the bus, we were there to greet and guide them to the staging area. After an introduction to HJ Andrews, the community partners, and the field trip agenda, each group journeyed into the forest to the first of their four stations.

Nestled at the end of the Discovery Trail was the River Reflections station. Here students learned about the complex interactions and disturbances that occur in a riparian zone through scientific observation and personal reflection. This station reflected the essence of the ongoing work at HJ Andrews by focusing on the Long Term Ecological Research and Long Term Ecological Reflections programs, highlighting the value of using both scientific and artistic lenses to understand the natural world. As scientists, the students compared the temperature, humidity, canopy cover, and species composition between two plots, one adjacent to the river and another 10-15 meters from the river. From our position on the creek bed, students saw a gravel bar in the middle of the river that provided a perfect example of the species found in newly disturbed areas. The students then journaled quietly by the river. To our surprise, students were so engaged in the journaling activity, they did not want to leave the station! Every student filled his or her own page in journals dedicated to collecting Canopy Connection’s Ecological Reflections.

Nestled at the end of the Discovery Trail was the River Reflections station. Here students learned about the complex interactions and disturbances that occur in a riparian zone through scientific observation and personal reflection. This station reflected the essence of the ongoing work at HJ Andrews by focusing on the Long Term Ecological Research and Long Term Ecological Reflections programs, highlighting the value of using both scientific and artistic lenses to understand the natural world. As scientists, the students compared the temperature, humidity, canopy cover, and species composition between two plots, one adjacent to the river and another 10-15 meters from the river. From our position on the creek bed, students saw a gravel bar in the middle of the river that provided a perfect example of the species found in newly disturbed areas. The students then journaled quietly by the river. To our surprise, students were so engaged in the journaling activity, they did not want to leave the station! Every student filled his or her own page in journals dedicated to collecting Canopy Connection’s Ecological Reflections.

At another station, students discovered the diversity found in old-growth forests, both in terms of composition and structure. They did this by identifying plants as tall as a western redcedar and as small as stairstep moss. Each student sketched and learned about a different plant and reported back to their group. After getting a close up view of forest biodiversity, the students embarked on a riddle quest to discover what makes an old-growth forest different from other forests. Every hidden riddle led them to a location on the trail identifying snags, woody debris, old trees, and canopy layers, which are the 4 main features of an old-growth forest. The students gathered in a circle to discuss how to mitigate threats to biodiversity through conservation measures.

At the “Stewardship in Action” station, the students reflected on the importance of taking care of nature by learning about and applying the Leave No Trace principles. Each student described their favorite place in the outdoors and how they felt there. This led to a discussion about the Leave No Trace principles. Students creatively expressed the principles through a short rap, poem or skit. The highlight of this station was applying the Leave No Trace principles by constructing and deconstructing a survival shelter using only debris found in the forest. The students were excited to get their hands on the branches and debris to build a shelter and crawl in for a picture!

At the “Stewardship in Action” station, the students reflected on the importance of taking care of nature by learning about and applying the Leave No Trace principles. Each student described their favorite place in the outdoors and how they felt there. This led to a discussion about the Leave No Trace principles. Students creatively expressed the principles through a short rap, poem or skit. The highlight of this station was applying the Leave No Trace principles by constructing and deconstructing a survival shelter using only debris found in the forest. The students were excited to get their hands on the branches and debris to build a shelter and crawl in for a picture!

The most profound experience was the tree climbe at the “To Affinity with Nature and Beyond” station. Each student had the opportunity to climb into the canopy of a 90-foot tall Douglas-fir tree using a system of ropes. Ascending the tree was a unique experience because students had to overcome any fears they might have had to get to the top of the tree. While climbing, students observed the change in temperature in the canopy layers and were surprised to discover that (on sunny days) it was 10 degrees F warmer at the top. While this station incorporates scientific observation, what most students will remember for the rest of their lives is the sheer wonder of viewing the old-growth forest from the canopy.

Between each station, the students found a compass bearingwritten on a slip of paper and hanging on a tree. This bearing led them to a riddle hidden 20-30 feet down the trail. The riddle related to the previous station the students had left not long before. This activity was a fun way to keep students engaged during the transition time between stations, while helping them reflect on what they learned at each station. The students learned how to read and use a compass, a valuable skill, while we were able to quickly assess if we met our learning objectives.

All in all, the Canopy Connections team spent over 1,800 hours to create and facilitate field trips for 6 middle schools and 230 students. While each field trip held the same content, every student left with his or her own distinct experience.

One student from Roosevelt Middle School said, “I learned a lot about old growth forests that I did not know before, and I think I am more likely to participate in activities taking place there.”

One student from Roosevelt Middle School said, “I learned a lot about old growth forests that I did not know before, and I think I am more likely to participate in activities taking place there.”

Throughout this program, our team and our students gained a great deal of knowledge, while fostering a connection to place and respect of old-growth forests. We have inspired our students to be curious, and want to learn more, about old-growth forests and the natural world. Ultimately, we hope these students will be more environmentally aware and will continue to care about the forest and natural environments as much as we do. As much as we hope to have touched their lives, the overall experience of working with these students has motivated us to continue pursuing careers in environmental education and work to nurture a healthier environment in the future.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Luvaas Family Foundation of the Oregon Community Foundation and Steve Ellis for their generous contributions that made these projects possible. Special thanks also to our community partners: the children, teachers and staff at Adams Elementary School, the McKenzie River Trust, Kathy Keable and Mark Schulze from HJ Andrews Experimental Forest, who hosted the field trip, and Rob Miron and Jason Seppa from the Pacific Tree Climbing Institute (PTCI), who facilitated the tree climb.

Works Cited

Jacobson, Susan Kay, Mallory D. McDuff, and Martha C. Monroe. Conservation Education and Outreach Techniques. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2006. Print

Louv, Richard. Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature-deficit Disorder. Chapel Hill, NC: Algonquin of Chapel Hill, 2008. Print

Sobel, David. Beyond Ecophobia: Reclaiming the Heart in Nature Education. Great Barrington, MA: Orion Society, 1996. Print

Kathryn Lynch is Co-Director of the Environmental Leadership Program. Katie is an environmental anthropologist who has a strong commitment to participatory, collaborative and interdisciplinary approaches in both her research and teaching. She has worked in Peru, Ecuador, Indonesia and the United States examining issues of community-based natural resource management. This has included examining the role of medicinal plants in Amazonian conservation efforts and the potential for engaged environmental education to promote conservation. Before joining UO she was a researcher at the Institute for Culture and Ecology, where her research focused on the relationships between forest policy and management, conservation of biodiversity, and nontimber forest products. She has also facilitated various courses and workshops that examine the nexus between environmental and cultural issues.

Kathryn Lynch is Co-Director of the Environmental Leadership Program. Katie is an environmental anthropologist who has a strong commitment to participatory, collaborative and interdisciplinary approaches in both her research and teaching. She has worked in Peru, Ecuador, Indonesia and the United States examining issues of community-based natural resource management. This has included examining the role of medicinal plants in Amazonian conservation efforts and the potential for engaged environmental education to promote conservation. Before joining UO she was a researcher at the Institute for Culture and Ecology, where her research focused on the relationships between forest policy and management, conservation of biodiversity, and nontimber forest products. She has also facilitated various courses and workshops that examine the nexus between environmental and cultural issues.

by editor | Jul 17, 2014 | Place-based Education

Place-based Education:

Listening to the Language of the Land and the People

By Clifford E. Knapp,

Professor Emeritus, Northern Illinois University

Introduction

Introduction

The intersection of place and education has occupied much of my teaching even though this field has not always been called place-based education. I began my career in 1961 as a high school science teacher. When I took my students outside to plant and identify trees, build nature trails, and predict weather, I described what we did as outdoor education. In 1972 when I taught seventh grade science we took field trips to the local water and sewage treatment plant, a geology museum, and a forest to study tree management practices. I described this as environmental education. Before I retired from teaching in 2001 as a professor in the Teaching and Learning Department of Northern Illinois University, I took my graduate students to a local bookstore to learn about its role in the community, on a walk in the business district to study architectural styles, and to an arboretum to observe tree damage from pollution. Only then, did I describe this way of teaching as place-based education.

In all three of these examples, I used the place and people in the community as living textbooks to teach parts of the curriculum that were best learned in context through direct experiences. I did this because I believed in experiential education and knew these people and places were the best teachers. The places in these communities were strong factors in my choices of what and how to teach. I viewed the curriculum through a lens that magnified opportunities to involve my students in authentic and engaging interactions with a more expansive classroom. Place-based education is an old idea and at the same time it is a new term and movement that evolved from its predecessors. This modern approach to teaching incorporates the best of the best practices, as educators understand them today.

David Sobel (2004) a pioneer in the field, described the term as “the pedagogy of community, the reintegration of the individual into her homeground and the restoration of the essential links between a person and her place” (p. ii). The first time the term was used in the United States was in his book and on a cover designed by The Orion Society (1998). Over time, place/education approaches have sported different names. This idea of teaching about the local environment has been called nature study (Wilson, 1916), bioregional education (Traina & Darley-Hill, 1995), ecological education (Smith & Williams, 1999), environment as an integrating context for learning (EIC) (Lieberman & Hoody, 1998), a pedagogy of place (Hutchison, 2004), and community-based education (Smith & Sobel, 2010). More recent names include contextual teaching and learning (Sears, 2002), watershed education (Michael, 2003) and life-place education (Berg, 2004). Another emerging synonym is environment-based learning.

All of these terms describe programs demonstrating how local places contribute to curriculum and instruction in schools and other educational institutions. Sometimes other descriptors are used to explain why extending education into the community is simply a good teaching technique. For example, in an article appearing in the Harvard Educational Review in 1967 the authors labeled their plan for school reform “a proposal for education in community” (Newmann and Oliver, 1967, pp. 95-101). The school building was where teachers planned, set objectives, and taught basic literacy skills to students. They went into the community to visit factories, art studios, hospitals, libraries and other laboratories to generate learning. The third part of their proposal was the in-school seminar where local “experts” helped students reflect on and apply what they learned in the community laboratories. In that same year the National Council for the Social Studies (Collings, 1967) issued a publication titled, How To Utilize Community Resources. It was designed to help teachers learn from their communities. In 1970 the National Science Foundation funded a curriculum project titled, Environmental Studies for Urban Youth (ES). “The student determines and investigates whatever is of interest to him within the available learning environment, both inside and outside the classroom” (Romey, 1972, p. 322).

Naming or labeling a teaching method or philosophy may make the idea easier to communicate to others, although it sometimes creates confusion about what that term really means. Jonathan Sime cautions: “The concept of place is reaching the early stages of academic maturity. Undoubtedly, there are confusions in the way the concept is used at present” (In Hutchinson, 2004, p. 12). This article defines place-based education, pedagogy of place, and sense of place. It gives examples of different types of educational programs having common characteristics at their core and explains why place-based education is an important educational reform. To provide historical perspective, I describe the Progressive Education reform movement in the United States, Great Britain, and other countries about 100 years ago. Finally, I compare that movement with the place-based education movement of today. My hope is to provide useful information, but mostly I want to stimulate your curiosity by raising questions. Niels Bohr, atomic physicist, told his students, “Every sentence that I utter should be regarded by you not as an assertion but as a question” (In Klose, 2009, p. 768). My hope is that my words will help you connect to places through a greater understanding of their educational potential.

Looking Back at Place-based Learning

Long ago, before schools were invented to educate the young, children learned from their families and from others in their communities. If they wanted to learn a trade, they apprenticed and were taught by a skilled master. If they wanted to cook, sew, and clean, they gained these skills from their parents. Comenius (1592-1670), an educational reformer, wrote: “We should learn as much as possible, not from books, but from the great book of Nature, from heaven and earth, from oaks and beeches” (In Quick, 1890, p. 77). Rousseau (1712-1778), a Swiss/French philosopher, believed: “His [the ideal boy’s] ideas are confined, but clear; he knows nothing by rote, but a great deal by experience. If he reads less well than another child in our books, he reads better in the book of nature” (In Quick, 1890, p. 118). Pestalozzi (1746-1827), a teacher from Zurich Switzerland stated, “nature offers the succession of impressions to the child’s senses without any regular order” (In Quick, 1890, p. 184). Throughout the history of schooling many educational reformers advocated for direct experiences in the community as a way to improve how students learned important knowledge. Later, when schools were established, instruction became more separated from the community and less experiential and practical educators today continue to offer school reform proposals in hopes of finding better ways to teach and learn.

The Progressive Education Movement

Public education has long been a contested arena in societies around the world. People continue to hold different views about how to educate students and what is important for them to know. When people become discontented with how schooling is conducted, they suggest educational reform. In the United States, beginning as early as the 1870s (Pinar, Reynolds, Slattery, & Taubman, 1995), a new progressive movement challenged the way students were educated. Critics did not like the way meaningless routines, rote memory, long recitations, regimentation, and passive learning characterized traditional education. There is no agreement on the exact dates of the progressive reform movement in the United States, but most historians agree that it flourished from the 1890s to the 1930s (Hines, in Squire, 1972). The Progressive Education Association was founded in 1919 and disbanded in 1955. Progressive Education was not a unified movement. At least three types were identified: 1) “child-centered, or children’s interest and needs approach”, 2) “the creative values approach”, and 3) “the social-reconstructionist approach” (Hines in Squire, 1972, p. 118).

John Dewey was one of the leading proponents of the child-centered approach in the United States. He also was known outside the country through his books, articles, and lectures. He promoted experiential education: “Experience [outside the school] has its geographical aspect, its artistic and its literary, its scientific and its historical sides. All studies arise from aspects of the one earth and the one life lived upon it” (1915, p. 91). He also wrote, “The teacher should become intimately acquainted with the conditions of the local community, physical, historical, economic, occupational, etc., in order to utilize them as educational resources” (1938, p. 40). Dewey outlined some common principles found in progressive schools: 1) promoting expression and cultivation of individuality (as opposed to imposition from above), 2) nurturing freedom of activity (as opposed to external discipline), 3) learning mainly through experience (as opposed to texts and teachers), 4) acquiring meaningful skills (as opposed to drill), 5) using the learning opportunities of present life (as opposed to preparation for a remote future), and 6) adapting to a changing world (as opposed to static aims and materials) (Macdonald, in Squire, 1972, p. 2). Progressive educators viewed the curriculum as ecological and linked to the broader community. Therefore it included what happened there as well as in the school building.

Whenever theoretical principles of a movement are briefly outlined like this, opportunities for misinterpretations are likely. This was true in the case of Dewey’s message and in much of the Progressive Education movement. Advocates for this movement point out how Dewey and other progressive educators were misunderstood (Squire, 1972; Wang, 2007; Tanner, 1997; Lauderdale, 1981). Because many educators interpreted Progressive Education differently and they discovered that implementing the theory and practice took hard work, the movement eventually lost power in the mainstream and was replaced by more traditional and abstract ways – mostly by transmitting knowledge through lectures and the written word. Progressivism never died out completely; it moved outside in the form of outdoor and experiential education (Knapp, 1994). In some cases, it re-emerged in schools (especially some private and charter schools) and nature centers. Some educators continue to implement progressive educational methods because they recognize that their students respond well to them. Do you know teachers and schools that could be called progressive today?

A Crisis of Place?

Why is a pedagogy of place important for educators to understand and implement? Some believe that today’s youth, especially in Western societies, are missing important connections to their surroundings. Phillip Sheldrake (2001) refers to this problem as a crisis of place characterized by “a sense of rootlessness, dislocation or displacement” (p. 2). Bill McKibben (1993) called this alienation from nature, rapid globalization, and loss of skills needed for self-sufficiency “a moment of deep ignorance, when vital knowledge that humans have always possessed about who we are and where we live seems beyond our reach. An Unenlightenment. An age of missing information” (p. 9). Laurie Lane-Zucker (as cited in Sobel, 2004) calls for a “fundamental reimagining of the ethical, economic, political, and spiritual foundations upon which society is based, and . . . this process needs to occur within the context of a deep local knowledge of place” (pp. i-ii). In a study of primary school children’s knowledge of natural and non-natural objects in the United Kingdom, the researchers found that after age 8, children could recognize more Pokemon characters than common local wildlife (Senauer, p. 7). “Few American schoolchildren can name more than a few of the plants or birds in their own neighborhoods, yet studies have shown the average American child can identify over one thousand corporate logos” (Michael, 2003, p. xii). Another indicator of “missing information” from today’s student knowledge base is that a recent edition of the Oxford Junior dictionary omitted many words related to nature. The following words have disappeared from the pages: dandelion, stork, otter, magpie, beaver, doe, minnow, wren and porcupine. They have been removed to make room for new words such as blog, broadband, and chatroom (River of Words personal e-mail communication, 2009). If you believe that today’s youth are in crisis by lacking connections to their local community, you may want to implement a pedagogy of place in your schools. One response to this crisis of place was the formation of the Children & Nature Network in 2006. Co-founders Richard Louv, author of Last Child in the Woods, (2008) and Cheryl Charles, former director of two leading environmental curriculum supplements (Project Learning Tree and Project WILD), led the way. Now the network is a strong force in promoting nature activities to combat “nature-deficit disorder” in the United States and Canada. I have attended the group’s national gatherings and find great energy and enthusiasm there.

A Pedagogy of Place

David Orr (1992) gives four reasons to integrate place into the educational curriculum. First, the study of a place requires teaching through “direct observation, investigation, experimentation, and application of knowledge” (p. 128). Experiential learning capitalizes on the rich content found in specific places. Problem-based learning in the context of place investigations has been shown to engage students actively and increase their understanding of required concepts. “Second, the study of place is relevant to the problems of overspecialization, which has been called a terminal disease of contemporary civilization” (Orr, 1992, p. 129). In other words, place involves the study of many interrelated disciplines. Place-based education demonstrates how knowledge from various content areas is needed to understand place at an ecological level. This is how learning originally occurred before educators divided up knowledge into separate and often unrelated compartments. Third, the study of place gives rise to many significant projects that serves to improve policy and practice in communities. These activities leading to more sustainable community practices can promote policy change related to “food, energy, architecture, and waste” (Orr, 1992, p. 129). Fourth, some view the destruction of local community life as a “source of the instability, disintegration and restlessness which characterize the present epoch” (Orr, 1992, p. 130). The study of place can serve to reeducate people in the art of living well where they are. To be an inhabitant there means a person who dwells “in an intimate, organic, and mutually nurturing relationship with a place” (Orr, 1992, p. 130). Do you know students who have a close relationship to where they live? Implementing a pedagogy of place enables educators to plan the instructional programs that spring from within the contexts of local areas.

A Sense of Place

My earliest contact with the concept of a sense of place came in the early 1970s from the artist Alan Gussow speaking at a conference. He described a place as a piece of the whole environment that was claimed by feelings (1974). This made sense because I learned best when I felt attracted to the content and saw it as meaningful to my life. I can remember special places from my childhood – the sandy beaches at the Atlantic Ocean, school athletic fields, a children’s camp, and the lakes and streams where I fished. I had feelings of excitement, joy, satisfaction, and security there. These places shaped my sense of self and eventually led to my career as a place-based educator. I agree with Hug’s (1998) definition that a “sense of place is the meaning, attachment, and affinity (conscious or unconscious) that individuals or groups create for a particular geographic space through their lived experiences associated with that space” (p. 79). Albert Camus described it this way: “Sense of place is not just something that people know and feel, it is something people do” (In Basso, 1996, p. 143). In order to have a strong sense of place a person has to been actively engaged in those places doing something important. This “doing” needs to raise a person’s level of awareness to a point that changes a person’s view of the place. How has your personal identity been influenced by the places you’ve been?

The idea of a sense of place is difficult to quantify, just like a sense of joy, sense of community, or sense of wonder are. However, this does not mean that the concept is not important. My sense of place is strong if I experience many positive feelings somewhere and it is weak if I feel disconnected to that place. However, there is a downside to being closely attuned to a place. If you move away or that place is harmed or destroyed you might feel sad or angry. When I was a child, I walked to school on a familiar path through a vacant lot of trees. I came to love some of the plants growing there, especially a plant called skunk cabbage. When that land was sold and a house built there, I felt a deep sense of loss and sadness. My special plant and path were gone. Losing a special place happened to me again as an adult. I live along a tree-lined river in my town. For years, I walked there to find peace and relaxation. I even built a trail and invited the community to share nature with me. I had fallen in love with that place because of the good feelings I found there. When the park district bulldozed the trees, leveled the land, and placed stone riprap on the shore, I felt another sense of loss of landscape. Whenever I go there I know my sense of place is violated. Have you ever lost a special place that had claimed your feelings?

Place and the Disciplines of Study

Disciplinary content in the study of place extends beyond art and education. According to Philip Sheldrake (2001) “place has become a significant theme in a wide range of writing including philosophy, cultural history, anthropology, human geography, architectural theory and contemporary literature” (p. 2). To this list Hutchinson (2004) added psychology and urban planning. Because place-based education includes many disciplines, it is well suited to being incorporated into much of the school curriculum. Gregory Smith (2002) described five different thematic patterns or models of place-based education in American schools. The first model, Cultural Studies, focuses on collecting information about the people living in an area. Students can interview these people and then write about their lives. The Foxfire program, begun in Georgia in 1966 by a high school English teacher, is one example of this model (Hatton, 2005). Many of these interviews and photographs became part of the Foxfire book series published by a major New York publishing company.

The second model, Nature Studies, emphasizes investigations of local natural phenomena. These studies lead to conservation and restoration projects to improve the local environment. Whenever one or more teachers in a school plan to teach students about their ecological addresses as well as their home addresses, they create a more knowledgeable citizenry. One example of this model is River of Words in Moraga, California (Michael, 2003). One project of this non-profit organization is promoting an international poetry and art contest for youth each year.

The third model, Real-world Problem Solving, involves the identification of community problems and issues. These problems and issues result from the clash between culture and nature. The student projects include learning about biology, physics, psychology, mathematics, economics, politics, and other subjects. One example of this model is promoted by Harold Hungerford and his colleagues at Southern Illinois University (Hungerford, Litherland, Peyton, Ramsey, & Volk 1996). Designed for middle school students (ages 10-14), this program helps students learn the steps for dealing with controversial place-based topics in the region.

The fourth model, Internships and Entrepreneurial Opportunities, explores the economic options available to students. Students examine various vocational possibilities by shadowing employees in local businesses or by taking on service learning assignments. The fifth model, Induction into Community Processes, allows students to become more involved in the life of the community’s decision-making processes by learning how local government works. By partnering with those agencies responsible for the day-to-day operations of a community, students become more engaged and responsible citizens. Smith’s five models show that place-based curricular reform takes several different forms. He identified some common elements in all models: 1) surrounding phenomena are the foundation for developing the curriculum; 2) students become creators of knowledge more than consumers of knowledge created by others; 3) students’ questions and concerns play a central role in what is studied; 4) teachers act primarily as “brokers” for connecting students to learning possibilities in the community; 5) separation between the community and school is minimized; and 6) assessment is based on how student work contributes to the well-being and sustainability of the community.

Implementing Place-based Education

It may be useful to envision what might happen if teachers or entire school staffs decide to implement place-based education. What might that look like in the lives of students, teachers, and administrators? All of these projections are based on some empirical studies, anecdotal evidence and my experience, but clearly more research is needed. For more information about the benefits of place-based education, I recommend reading Andrew Kemp’s (2006) chapter, “Engaging the environment: A case for a place-based curriculum” (pp. 125-142). Another reference is fact sheet #2 available from the University of Colorado at Denver (www.cudenver.edu/cye). Smith and Sobel’s book, Place- and Community-based Education in Schools (2010) gives a powerful rational for implementing this approach in schools.

The most obvious outcome of a well-taught place-based curriculum is that students develop a strong sense of place for where they live. They feel rooted and connected there. They know the history of their place and discover where to find beauty as well as blight. They have a better sense of their personal identities because there is a positive relationship between knowing your place and knowing yourself. Students grasp how the community officials make decisions affecting their daily lives. They also know more about the critical issues facing the local government and may get involved in some of them. Students become aware of their own ecological ethic and want to take steps to maintain the community’s sustainability into the future. They demonstrate a reverence for life and a love of nature and are motivated to care for local ecosystems. They want to learn more about their place because they experience the joy and satisfaction of learning relevant concepts, skills, and values. They find many opportunities to apply the concepts, skills and values learned at school. Students improve as team members as more and more community projects are completed cooperatively. They are able to move between the school building and the rest of the community with greater ease and confidence.

Because of the students’ enthusiastic responses to learning, teachers look forward to going to school each day. Teachers notice that their classroom climate has improved as a result of a curriculum that engages students. Teachers realize that the students are retaining information learned in meaningful contexts and scores on certain tests and other indicators are slowly rising. Teachers look better in the eyes of their administrators and receive more acknowledgements. They realize that students are learning about their place through a variety of disciplines, including mathematics, science, history, government, language, art, music, and physical education. Teachers are able to teach their students about higher order executive functions (habits of mind) such as asking better questions, critically analyzing, problem solving, and evaluating their own thinking processes through lessons about place. They set textbooks aside in favor of learning through direct experiences and new information found in the community. They lecture less and let the places and the residents do more of the teaching. Their main role is to facilitate learning more than transmit knowledge. Teachers gain confidence in their ability to build challenging curriculum from the rich contexts in their community and surrounding region. They feel like creative and innovative educators and not mere technicians of a scripted curriculum.

If all of these transformations became visible in students and teachers, school administrators will be deeply satisfied. They will receive frequent praise from parents and other members of the community for running a successful school. They will boast to their fellow administrators about a school reform that works. The positive school climate will reflect a healthy place to be. Place-based education will have contributed to helping the school fulfill its critical role in the community.

Theologian and geologian, Thomas Berry (2006) wrote: “Two things are needed to guide our judgment and sustain our psychic energies for the challenges ahead: a certain alarm at what is happening at present and a fascination with the future available to us if only we respond creatively to the urgencies of the present” (p. 17). I hope that you share some of the alarm I feel about today’s youth becoming alienated from their local natural and cultural worlds and will respond to the urgencies of the present with plans to teach more about your local places.

References

Basso, K. H. (1996). Wisdom sits in places: Landscape and language among the Western Apache. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press.

Berg, P. (2004). Learning to partner with a life-place. (Reprint first appearing in Ecuador Dispatch #1, June 12, 2004).

Berry, T. (2006) Evening thoughts: Reflecting on earth as sacred community. San Francisco, CA: Sierra Club Books.

Collings, M. R. (1967). How to utilize community resources. Washington, D.C.: National Council for the Social Studies. (How To Do It Series—No.13).

Dewey, J. (1915). The school and society (Rev. ed.). Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience & education. New York: Collier Books.

Gussow, A. (1974). A sense of place. New York: Seabury Press.

Hatton, S. D. (2005). Teaching by heart: The Foxfire interviews. New York: Teachers College Press.

Hines, V. A. (1972). Progressivism in practice. (Pp. 118-164). In J. R. Squire, (Ed.). A new look at progressive education. (Pp. 1-13). Washington, D.C.: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Hug, J. W. (1998). Learning and teaching for an ecological sense of place: Toward environmental/science education praxis. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Pennsylvania State University, State College.

Hungerford, H. R., Litherland, R. A., Peyton, R. B., Ramsey, J. M., & Volk, T. (1996). Investigating and evaluating environmental issues and actions: Skill development program. Champaign, IL: Stipes Publishing.

Hutchison, D. (2004). A natural history of place in education. New York: Teachers College Press.

Kemp, A. T. (2006). Engaging the environment: A case for a place-based curriculum. In B. S. Stern (Ed.), Curriculum and teaching dialogue: Volume 8. (pp. 125-142). Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

Klose, R. (2009). Atoms vs. a three-legged woman. Phi Delta Kappan 90(10). Pp. 767-769.

Knapp, C. E. (1994). Progressivism never died—it just moved outside: What can experiential education learn from the past? The Journal of Experiential Education, 17(2), 8-12.

Lauderdale, W. B. (1981). Progressive education: Lessons from three schools. Bloomington, IN: Phi Delta Kappa Educational Foundation.

Lieberman, G. A., & Hoody, L. L. (1998). Closing the achievement gap: Using the environment as an integrating context for learning. San Diego, CA: State Education and Environmental Roundtable.

Louv, R. (2008). Last child in the woods: Saving our children from nature-deficit disorder. Chapel Hill, NC: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill.

Mary Baldwin College. (n.d.). Taking natural teaching to a higher level. (Flier available at twillis@mbc.edu)

Macdonald, J. B. (1972) Introduction. In J. R. Squire, (Ed.). A new look at progressive education. Washington, D.C.: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

McKibben, B. (1993). The age of missing information. New York: A Plume Book.

Michael, P. (Ed.). (2003). River of words: Images and poetry in praise of water. Berkeley, CA: Heyday Books.

Newmann, F. M., & Oliver, D. W. (1967). Education and community. Harvard Educational Review, 37(1), 61-106.

Orr, D. W. (1992). Ecological literacy: Education and the transition to a postmodern world. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Pinar, W. F., Reynolds, W. M., Slattery, P., & Taubman, P. M. (1995). Understanding curriculum: An introduction to the study of historical and contemporary curriculum discourses. New York: Peter Lang.

Quick, R. H. (1890). Essays on educational reformers. New York: E. L. Kellogg & Company.

River of Words e-mail. info@riverofwords.org retrieved July 17, 2009.

Romey, W. D. (1972). Environmental studies (ES) Project Brings Openness to Biology Classrooms. The American Biology Teacher, 34(6): 322-328.

Sears, S. (2002). Contextual teaching and learning: A primer for effective instruction. Bloomington, IN: Phi Delta Kappa Educational Foundation.

Senauer, A. (2007). Children & Nature Network Research and Studies, Volume Two. Santa Fe, NM: Children & Nature Network. Retrieved September 6, 2009, from http://www.childrenandnature.org/research/volumes/C42/42

Sheldrake, P. (2001). Spaces for the sacred: Place, memory, and identity. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press.