by editor | Sep 20, 2013 | K-12 Classroom Resources

What is your current job title?

What is your current job title?

I am self-employed as an environmental education and research consultant – my company is Staniforth & Associates, so I guess I am the principal!

How did you get into this field?

I worked as a field biologist for years, researching large mammals, particularly whales off the east coast, the Gulf of Mexico, and Galapagos. The work was fascinating, and much of it involved working with local people and resource conflict issues with the whales (e.g. humpbacks getting caught in fishing gear, dolphins and seals perceived to be eating “all the fish”). I felt somewhat frustrated that our findings were not getting out to the public at all – the main audience for being more aware of, interested in and acting for these animals and their habitat. Public awareness and education seemed to me to be the most important tool for raising awareness and deepening connections to the natural world, to foster conservation efforts, so I went back to school to complete an MSc in Environmental Education.

What are you working on right now?

I have been doing quite a bit of evaluation work of late, both with education programs for non-profits as well as larger scale programs – and recently finished a province-wide evaluation of BC’s idle reduction programs, for municipalities, governments, corporate fleets, schools and communities.

What did the evaluation of the idle reduction program show?

Very interesting results: we surveyed many stakeholders and analyzed a wide range of idle reduction programs, including municipalities, corporations, NGO’s, provincial and federal initiatives, school programs and fleet projects. Generally programs have been successful, particularly ones involving fleets of vehicles, were significant reduction gains were recorded. Ones targeting urban audiences were also effective. Idle reduction initiatives were seen to be “gateway” programs: an easy first step or starting point to beginning more substantive sustainable transportation efforts. Programs showing the most success had a combined approach: involving policies such as bylaws (the “stick” approach”), combined with community-based awareness, education, incentives and technology components.

What is your favorite part of your job?

The great and somewhat unpredictable variety of consulting work – and the wonderful educators, scientists and students I get to meet and be inspired by/learn from!

Has there been an incident during your work that stands out as particularly memorable or that reaffirmed your belief in what you are doing?

Hmmm – that’s a good question – working with young people in nature is always rewarding – you get those precious “ah ha” moments when you get to witness their wonder, excitement, delight , in a discovery. This happens of course with adults as well. I guess also there have been some reaffirming times when long hours of conservation and awareness work have shown good results in a policy change or areas protected – not enough of these alas, but they are significant and need celebrating!

If you could change anything about your work, what would it be?

I would love to see the critical stewardship, conservation and public engagement work out there that so many of us do as volunteers with non-profits prioritized by governments and corporations, and funded accordingly. More and more critical stewardship, research and restoration work is being off-loaded onto community volunteer groups, due to funding cuts – a serious situation.

Where do you find inspiration for the work you do?

From the environment itself: my passion for the natural world – and from working with young people – children have such an innate connection to nature, and their curiosity, playfulness, compassion and openness is inspiring and rejuvenating.

What is your favorite resource or tool for teaching about the environment?

That is a hard question! I have so many – but probably just being outside – getting people of all ages outdoors and awakening their senses, re-connecting us all to the natural world.

Where do you go when you want to recharge your batteries?

I take my dog for a walk by the ocean – just being by the sea, breathing in the salt air and hearing the waves breaking is incredibly therapeutic.

What is your favorite place to visit in the Pacific Northwest?

Another very hard question…! I love the glaciated peaks of Strathcona Park on Vancouver Island and of course, the vastness of Long Beach National Park … and so many other places!

What is your favorite nature/environment book?

Hmmmmm ……..I love anything by Loren Eiseley, Rachel Carson’s A Sense of Wonder, all Mary Oliver’s poems, …. lots more!

Who do you consider your environmental hero?

I have a few, but Rachel Carson is probably my main hero and inspiration – both for her excellent research as a scientist, her determination to put forward her research against huge obstacles, and her wonderful writing and love of nature.

Thanks for your time. Do you have any final thoughts about your work in environmental education, or words of advice to those following in your footsteps?

Just do it, if education calls to you. For many people involved in conservation and stewardship work, the stress and grief and powerlessness of experiencing special places, ecosystems, endangered habitats, species – being lost or degraded is devastating, and often leads to burnout and despair. Working in education and public awareness I believe is the only real tool we have that will effect long term changes for the planet – it is what keeps me and many educators going, and brings many benefits. (Income…?? not so much !)

by editor | Sep 3, 2013 | K-12 Classroom Resources

Plants and People

Three service learning teams from the University of Oregon Environmental Leadership Program tackle teaching children about the ecological and cultural importance of native plants.

.

.

by Kathryn Lynch

Environmental Leadership Program

University of Oregon

Read the article here:PlantsandPeople

by editor | Aug 28, 2013 | K-12 Classroom Resources

Ralph Harrison is the 2013 winner of the EPA’s Presidential Award for Innovation in Environmental Education. We caught up to him as he was heading for Alaska and managed to get some insight into his personal perspectives and motivations as a teacher of environmental science.

What is your current job title?

I’m the Science Department head at the Science and Math Institute in Tacoma Public Schools.

How did you get into this field?

I hold Bachelor’s degree in Science Education Central Washington University and Masters in Biology from Washington State University. I’ve been an active member of the Washington State Science Teachers Association Board for ten plus years. I advocate for high quality science teaching, experiential learning, and inquiry-based learning.

And how did your current position come about?

I worked as a founding teacher of Tacoma School of the Arts (SOTA), and focused my time to develop a quality science and math program in an arts-focused highschool. I believe strongly in the importance of high quality science instruction for all students 9-12th grades and integration with the arts. From work with my colleagues at SOTA, we hatched the idea for SAMI, another community partnership school at Point Defiance Park, where the 702-acre park setting became the classroom. I worked with a team as one of the founding teachers of Science and Math Institute high school.

The natural beauty of the park inspired an environmental science focus for the school. From there, I developed a full outdoor education science program that included phenology of plants and animals.

What is your motivation for this work?

I’m passionate about making a difference in science and environmental education for students and creating schools where students and teachers capitalize on community assets. Students find their passion through relevant learning; their success is the focal point.

What are you working on right now?

I’m working to develop partnerships with local and national organizations. One I’m particularly excited about is with the USA National Phenology Network. SAMI students in outdoor education classes will be integrating their phenology gathering fieldwork into the national database. I’m also working to integrate our school’s robotics program into field gathering instruments. The students and I are building a hexacopter to act as a data gathering platform to research 150-foot tall Douglas Fir tree snags in the park.

What is your favorite part of your job?

Being able to be outside with students researching and actively learning in the park’s forests.

If you could change anything about your work, what would it be?

I’m passionate about students participating in relevant, active, learning, research and science. As technology and the advancement of science continues at a lightning pace, I want the students to have access to the most current instruments and protocols so that they’re learning is relevant and timely. I struggle to provide these materials with limited resources. That’s why I consistently seek partnerships.

How do you feel about the Next Generation Science Standards?

I’m all in on standards based teaching as well as Professional Learning Communities (PLC’s). PLC’s bring the old and new together, and form common strategies, voice, and collegiality. The SOTA and SAMI staff work hand-in-hand to bring the NGSS and the Washington State Standards in a common voice to the students. I cite a 30% jump of test scores in the Washington Biology End of Course exam this past year as evidence that standards based teaching as well as PLC’s have a dramatic impact.

Where do you find inspiration for the work you do?

I have the great privilege of living near Point Defiance Park on Salmon Beach (Google earth it and you’ll see what I mean), an old community built on pilings 100 years ago right below the park I work at. I want to share with the students the natural resources that I’ve come to know love.

What is your favorite resource or tool for teaching about the environment?

My collection of various field guides from all over the Pacific Northwest, like my favorite, Pojar& MacKinnon’s Plants of the Pacific Northwest Coast.

Where do you go to recharge your batteries?

I’m an avid fly-fishermen and enjoy travelling throughout the Northwest enjoying the environments I visit as I fish.

What is your favorite Nature / Environment book?

Trees, Truffles and Beasts by; Chris Maser, Andrew Claridge, and James Trappe.

Who do you consider your environmental hero?

My colleague and friend Ken Luthy, who I’ve worked with for twenty three years, teaching together and starting schools. I’m inspired by his passion for the environment, his time spent as a National Park Ranger during the summer months, and his dedication to teaching high school and learning.

What words of encouragement would you give a new science teacher just entering the classroom?

It takes years to truly get the hang of teaching science. Work with your colleagues to make science instruction the highest quality and relevant to your students and community. Seek out what your communities assets are and use them. Bring your class outside of the walls that define your school, especially with regards to Environmental Education.

by editor | Aug 24, 2013 | K-12 Classroom Resources

by Kevin Beals & Craig Strang

magine a residential outdoor science program where instructors—all of them—routinely combine their passion for the natural world with a deep understanding of research-based teaching approaches that are based on all we know about how people learn. BEETLES (Better Environmental Education, Teaching, Learning, Expertise & Sharing), funded by the S.D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, is a new project at Lawrence Hall of Science, University of California, Berkeley that designs professional development experiences for program leaders to use with their teaching staffs.

magine a residential outdoor science program where instructors—all of them—routinely combine their passion for the natural world with a deep understanding of research-based teaching approaches that are based on all we know about how people learn. BEETLES (Better Environmental Education, Teaching, Learning, Expertise & Sharing), funded by the S.D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, is a new project at Lawrence Hall of Science, University of California, Berkeley that designs professional development experiences for program leaders to use with their teaching staffs.

A group of 15 sixth grade students and their classroom teacher are on a hike led by a field instructor at a residential outdoor program. They come across a bracket fungus on the ground. The instructor, who has participated in BEETLES, calls out, “NSI,” a routine the students now recognize as Nature Scene Investigators. Quickly half the group kneels around the fungus in a tight circle. The other half stands in a circle around the inner circle.

(note: the discussions in this article are actual transcripts taken from trail hikes)

Instructor: OK, let’s hear some observations from the inner circle.

Student: It’s light.

Student: it looks charred.

Student: It looks like it’s broken off something.

Student: It looks like wood.

Student: It looks like it’s from a tree.

Instructor: Now let’s hear some questions from the outer circle.

Student: What does it feel like?

Instructor: OK, someone from the inner circle, can you say what it feels like?

Student: It’s rough here but smooth here.

Student: It feels smooth on the outside and rough on the inside.

Instructor: So, Kendra and Amir, would you agree that it’s smooth on the outside and rough on the inside?

They both examine it closely.

Student: Yep.

Student: I agree.

The students share more observations and questions, and continue to do so after the two circles have switched places and roles.

Instructor: OK, now I want you all to come up with explanations about it. Don’t forget to use evidence in your explanations.

Student: I think it was on a tree that got burned and it fell off and my evidence is because it’s black.

Instructor: Hey, did you all notice that Jared said, “I think…?” In science discussions, it’s good to use language of uncertainty, like “I think…” or “I wonder if…” because in science, you always need to be open-minded to other explanations and ideas if you find new evidence.

The students come up with several other explanations.

Instructor: Now does anyone have something to share about this that they’ve heard or read about somewhere else? But be sure to tell us your source of information.

Student: I think it’s a fungus, because we learned about fungi with our gardening teacher at school, and it looks like some of the fungi we studied.

Student: I’ve heard that they’re decomposers, and they turn dead things into dirt. I heard that from my teacher.

Instructor: This is a fungus. I’ve read that these are a type of fungus that grows on trees called bracket fungus or shelf fungus. I’ve also read that they are just the “fruit” of the fungus, and that most of the fungus looks like white threads and is spread out inside the wood. My source is a book written by a fungus expert. The book is called Mushrooms Demystified. We’re going to be checking out mysteries like this all day. We’ll be finding cool stuff, making observations, asking questions and trying to explain what we find.

Classroom Teacher: I just want to say, the more stuff you all pointed out the more I looked. You got me to look at it differently.

Instructor: Yeah that’s a great point and that’s one reason scientists often work in teams.

Student: Hey look, there’s one of those things on this tree.

Students excitedly swarm around a nearby tall stump with a few small bracket fungi on it.

Instructor: So what do you guys think now that you have this new evidence?

Student: It does grow on trees! It’s not burned because this tree isn’t burned and it’s still black.

Instructor: Is this tree alive or dead?

Student: Alive. No, wait. It’s just a big stump.

Instructor: As we hike, let’s keep our eyes out for more of these fungi and see what we find. Let’s see if we find any on living trees, or if they’re just on dead trees, like this one.

Classroom Teacher: (aside to instructor) I had no idea when I got on this hike it was going to be like this, because other hikes I’ve been on have been more about just delivering information. I want to learn as much from you as I can today about how I can do this with my students back at school.

What’s significant about this actual account, compared to many other outdoor science activities? Is any learning taking place? Why were so many student questions left unanswered?

We like NSI precisely because so much learning (and engagement) is going on. It sets a tone of inquiry, exploration, figuring things out and discussion of ideas. We want students’ minds to be at least as active as their feet. We want the students, not the instructor, to be making discoveries, asking questions, and trying to explain what they find. The instructor guides, but most of what happens is student-driven. This may look like the instructor isn’t doing much, but it is actually far more nuanced than blurting out three facts and a chant about bracket fungi.

Student (shown in photo): I feel like a scientist today.

Student: I know, I’ve never done this before.

Student: Yeah, I’ve been to the woods before, but not discovering and stuff like this.

Student: I didn’t even know I could do this.

Student: I’m gonna do this at the park near my house!

Activities like NSI taught by instructors who know how to look for evidence in the minds of learners as well as for evidence on the trail, engage students in the scientific practices called for in the soon to be published Next Generation Science Standards (National Research Council 2012) that are certain to be adopted by nearly every state in the US: asking questions, carrying out investigations, constructing explanations, engaging in argument from evidence, and obtaining, evaluating, and communicating information. Those are tricky things to teach in a classroom, but in a rich outdoor setting, students are surrounded by opportunities to explore and investigate with these practices. Instructors have opportunities, if they know how to take advantage of them, to help students make careful observations, work together, communicate their ideas, disagree politely, remember to base their explanations on evidence, use language of appropriate uncertainty, and cite their sources of information. These thinking skills lead directly to meaning making—a very different outcome compared to memorizing the names of trees or the three different types of decomposers. And there is an added benefit. When students are talking, instructors get to hear and understand their ideas about science topics. Effective instructors build their teaching on student’s ideas, but they can only find out what those ideas are by letting students express them!

Outdoor science schools are perfectly situated to help indoor schools by focusing their teaching on scientific practices. In a rich outdoor environment with long days, myriad inquiry opportunities and a skilled instructor, students can accomplish more in a few days than they might be able to in months in a classroom.

BEETLES is designing professional development experiences that help instructors to become expert users of approaches and tools like NSI that:

• are more student-centered, less instructor-centered.

• are less about an instructor telling students information, and more about instructors giving students chances to explore, investigate and figure things out themselves.

• are less about convincing students their instructor is ”awesome,” and more about making students feel smart and capable, moved more by what nature has revealed to them than by what their instructor has revealed to them..

• empower students with skills to use when they no longer have a field instructor leading them.

• facilitate student meaning-making.

• increase students’ wonder and curiosity about the natural world.

• are less about games or activities that can be done on a playground, and more about engaging students with investigating the natural world.

Historically, investments have not been made in the development of research-based professional development and curriculum for outdoor science programs. Unlike in K-12 schools, field instructors often rely on word-of-mouth “traditions,” and tattered copies of activity outlines passed around in bruised binders. BEETLES is designing, field testing, documenting and evaluating a series of professional development sessions, each of which presents instructors with a lens through which to view and improve outdoor science instruction.

BEETLES is also creating content sessions to help field instructors grapple with their own understanding of foundational concepts basic to many outdoor science schools: cycling of matter, flow of energy, adaptation and evolution. Finally, BEETLES is designing and collecting activities, like NSI, that reflect research-based approaches and accurate science, for use in the field with children. All these materials will be available, free, via a website.

BEETLES is hosting a 5-day California Leadership Institute during Summer 2013. Pairs of leaders will be invited from 12 different outdoor science schools throughout the state. The leaders will experience the professional development sessions, activities and hikes, share their own expertise, and plan out staff training for their own staffs. We hope to empower program leaders with new materials and perspectives, but also to benefit ourselves by capturing improvements and adaptations made by the leaders.

In 2014 & 2015, BEETLES will offer a National Leadership Institute, open to program leaders around the country. Eventually the BEETLES web site will offer supporting videos that show how the activities and professional development sessions are actually led with students and staffs.

The following is from an email sent to us by a field instructor a week after she participated in a 3-day BEETLES professional development workshop:

I wanted to relay a small snippet of some kid feedback I got this week on trail. The teachers had the kids write us all notes thanking us for their week, and it was interesting the things that popped up, besides the usual “You’re the coolest everrrrrrr” messages. One note included the following: “…We learned a lot from you, because, unlike other teachers, you go in-depth on everything we learn instead of going like ‘Here’s this’ and ‘This is that.’” I know I’ve been a “Here’s this” naturalist in the past, and throughout this week was really conscious of letting kids discover and asking them broad questions, and what a cool thing to hear back the first week testing it out! Several kids mentioned NSI in their notes, and as someone who has been a naturalist for 5+ years, it was a wonderful experience this week having a new lens to look through and launch the year with. It is wonderful to continue the learning process myself, and have new tools, and test them out, and watch some of them be wildly successful. Those kids were on the edge of their seats by the end of the week after we’d noticed, wondered, and built new frames of reference and pieced together evidence for what it reminded us of for days as to what the green lacy stuff on twigs really was. Never have I had children so excited about lichen and figuring out what it was! I just wanted to share with you, because I am excited to continue experimenting with what we learned, and pass the results on.

# # #

BEETLES invites outdoor science school instructors and leaders to participate in the development of our materials and program, and to participate in our leadership institutes. Kevin Beals (kbeals@berkeley.edu) & Craig Strang (cstrang@berkeley.edu) are the founders of BEETLES. Please visit www.lawrencehallofscience.org/beetles.

by editor | Aug 23, 2013 | K-12 Classroom Resources

Dr. Peter McInerney et al. review the literature related to the theoretical foundations of place-based education (PBE). They propose that the main task of PBE in schools is “creating opportunities for young people to learn about and care for the ecological and social wellbeing of the community they inhabit and the need to connect schools with communities as part of a concerted effort to improve student engagement and participation.” Further, they argue that a critical perspective in PBE “encourages young people to connect local issues to global environmental, financial and social concerns, such as climate change, water scarcity, poverty and trade. At the end of the article the authors propose several approaches to facilitate critically engaged forms of learning:

Give students a say in what and how they learn;

Encourage young people to engage with the big question confronting the global community;

Build relational trust within schools and communities;

Develop a sense of student ownership, identity and belongingness;

Create space for dialogue, reflection and political action;

Establish an ethical commitment to justice.

McInerney, P., Smyth, J., & Down, B. (2011). Coming to a place near you? The politics and possibilities of a critical pedagogy of place-based education. Asia-Pacific journal of teacher education, 39(1), 3-16. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2010.540894

From NAAEE website Posted By Alex Kudryavtsev

by editor | Aug 21, 2013 | K-12 Classroom Resources

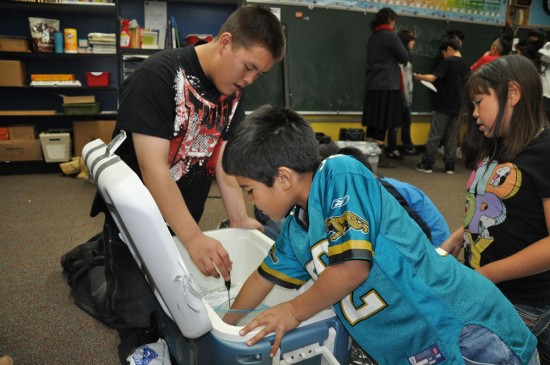

Middle school students from St. Paul School, Alaska, discuss a timeline of the northern fur seal’s annual cycle, moving plastic animals to show how the fur seal rookery structure changes over the year.

by Lisa Hiruki-Raring

AFSC Education Coordinator

Alaska Fisheries Science Center

National Marine Fisheries Service, NOAA

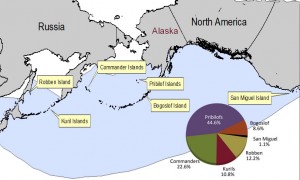

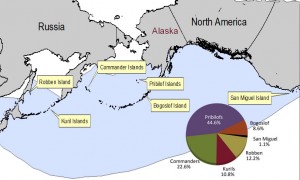

n a small group of islands in the middle of Alaska’s Bering Sea, half of the world’s population of northern fur seals gathers each summer to breed on crowded rookeries, alive with the calls of mother fur seals, their pups, and adult males defending territories. The Pribilof Islands, legendary to the Russians of the 1700s for their wealth of seal pelts, were the central location of the commercial harvest of fur seals from the mid-1700s until 1984. The northern fur seal has always been an integral part of the history, culture and ecosystem of the Unangam (Aleut)

n a small group of islands in the middle of Alaska’s Bering Sea, half of the world’s population of northern fur seals gathers each summer to breed on crowded rookeries, alive with the calls of mother fur seals, their pups, and adult males defending territories. The Pribilof Islands, legendary to the Russians of the 1700s for their wealth of seal pelts, were the central location of the commercial harvest of fur seals from the mid-1700s until 1984. The northern fur seal has always been an integral part of the history, culture and ecosystem of the Unangam (Aleut)

community in the Pribilof Islands. Although the Unangan knew of the Pribilof Islands, there were no settlements there until Russian fur hunters moved the Unangan from the Aleutian Islands to the Pribilof Islands to harvest fur seals for them in the mid-1700s.

A female northern fur seal calls to her pup on the rookery.

Because of the northern fur seal’s significance to the people of the Pribilofs, the Aleut Community of St. Paul Island-Tribal Government (TGSPI) and the Pribilof School District wanted to develop a comprehensive northern fur seal curriculum to address northern fur seal natural history, the cultural importance of northern fur seals to the Unangan, the history of the fur seal commercial and subsistence harvest, and research, conservation, and sustainability of the northern fur seal population.

A Collaborative Effort

Educators from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Alaska Fisheries Science Center (NOAA/AFSC) in Seattle, WA worked closely with the Pribilof School District and TGSPI to develop “Laaqudax, the Northern Fur Seal,” a curriculum integrating science, math, language arts, culture, history and art into an engaging course on northern fur seals. With funding to develop the curriculum provided by NOAA and the Central Bering Sea Fishermen’s Association (CBSFA) of St. Paul Island, the curriculum was truly a community effort.

Local Relevance

AFSC educators are in a unique position to create this curriculum. Federal government scientists have been studying fur seals on St. Paul and St. George Islands in the Pribilof Islands for over 100 years, with data extending back to government counts of fur seals in the 1920s, and commercial harvest records extending back to 1867. AFSC educators worked directly with NOAA Fisheries researchers and TGSPI staff to incorporate current research and traditional ecological knowledge into the Pribilof School District science curriculum while encouraging stewardship of the natural environment.

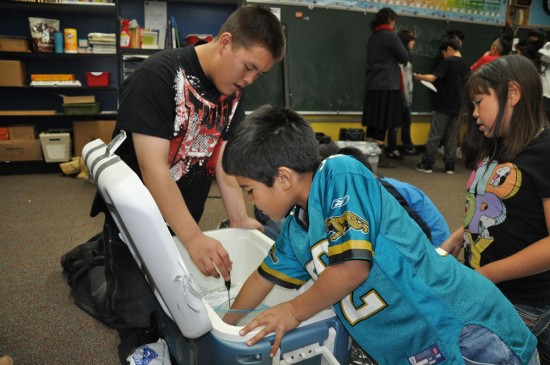

7th grade students help 4th grade students investigate adaptations to diving.

A challenge in creating the curriculum was that rural schools in Alaska often have high educator turnover, and most new teachers from outside Alaska are unfamiliar with local ecosystems and Alaska history. Additionally, even teachers who have worked in rural Alaska for many years may not have any basic knowledge about the animals closest to their schools. To address this need, the northern fur seal curriculum provides information and activities that can be taught by teachers without background knowledge of the Bering Sea ecosystem and Unangam culture. The curriculum also incorporates traditional ecological knowledge and cultural perspectives and provides activities across several subjects so that teachers can meet educational standards in a variety of areas while focusing on northern fur seals. For example, Lesson 1 (“What is a fur seal?”) includes activities on taxonomy and classification (science and math), graphing (science, math), a Venn diagram (science, math, language arts), a diagram of seals labeled in Unangan (science, culture), a writing exercise to describe a seal (science, language arts), and a physical activity about how seals and sea lions walk and swim (science, physical education).

8th grade students count seals…

A Curriculum with a Multi-grade Structure

The curriculum was developed as a spiraling curriculum, a curriculum that uses the same subject area for all grades but goes into deeper levels for older students. For example, kindergarteners learn that fur seals eat fish,

while middle schoolers use reference keys to identify fish bones from fur seal diet samples, and high schoolers analyze actual data to compare what fish are eaten at different fur seal rookeries on the Pribilof Islands. The curriculum is structured so that the first three lessons introduce students

…and a 6th grade student records observations at the rookery.

to fur seals, the Unangam people and culture, and fur seal rookeries. Subsequent lessons tackle what fur seals eat, adaptations to diving, and winter migrations. Middle and high school students have more complex and data-driven exercises, including lessons on the commercial harvest of fur seals, population management, and the Marine Mammal Protection Act. All lessons and activities have been aligned to Alaska State Educational Standards and Ocean Literacy Principles, and will be aligned to the new Common Core Standards and the upcoming 2013 Next Generation Science Standards.

Testing the Curriculum

In September of 2011 and 2012, AFSC educators worked with students and teachers from St. Paul School to test activities from the northern fur seal curriculum. Whenever possible, teachers are encouraged to collaborate and teach across subject areas, to promote interactions between students from different grades. In 2012, high school students studying Russian read Rudyard Kipling’s story “The White Seal,” talked about the origins of the names of the characters in the story, wrote the names in Cyrillic script, and discussed whether events depicted in the story were accurate or fictional. Language arts students in 10th -12th grades compared a timeline of events (1700s to the present) from a St. Paul Island community perspective to a more general historical timeline, then joined the 9th grade math class, who had graphed fur seal commercial and subsistence harvest numbers from 1860-2010. Together, the students looked at how the historical events coincided with fluctuations in commercial fur seal harvest numbers and discussed subsistence harvest from the 1980s-2010.

Students and parents investigated fur seal activities during the parent-teacher conference day.

Highlights of the curriculum testing included:

• middle school students helping younger students learn about adaptations of fur seals for diving

• high school students creating rubber stamps of fur seals and helping first, second and third grade students make murals of a fur seal rookery with the stamps

• field trips for seven classes (K-12) to visit the observation blind at a fur seal rookery near the school, where students observed fur seal behavior and discussed the difficulties scientists have to accurately count seals at the rookery

• community outreach during parent-teacher conference day, where fur seal activities were set up in the school lobby to engage parents

• presenting an overview of the curriculum to all teachers from St. Paul and St. George schools during a school inservice day

• teaching students from St. George School (10 students, 1st-10th grade) by videoconference

• an impromptu lesson by students on how to use an Aleut yoyo (a fur seal rib bone, twirled around the index finger)

Students and educators learned a great deal from one another: educators learned about the process for stretching and drying the fur seal throats (esophagus) to make traditional Unangam clothing, and high schoolers engaged in a spirited discussion of the subsistence harvest and the role it still plays in their lives. Through the 2 ½ years of development of this curriculum, NOAA fur seal scientists have also taken part in educational and summer camp events with the school and community on St. Paul Island, using fur seal activities for informal education. The success of this project is due to the collaboration of its partners, each of whom brought different skills and perspectives to the development of the curriculum.

Access and availability

Once the curriculum is complete, it will be available free of charge on the AFSC education website (http://www.afsc.noaa.gov/education/), in two grade bands (K-6 and 7-12). The elementary curriculum will be available in early 2013; the middle/high school curriculum’s estimated date of completion is fall 2013.

_____________________

SIDEBAR: Evaluation and Assessment

Because the curriculum is in the final stages of development, a formal evaluation and assessment framework has not been completed. Short-term evaluation of material is conducted by individual teachers (e.g., writing assignments and quizzes), and most activities have some aspect of assessment in the form of worksheets and maps. The AFSC educators have been evaluating the effectiveness of specific activities through focal group discussions with teachers and individual feedback from students and teachers. The structure of each class is unique every year in small rural schools, depending on the number of students in each grade. For example, at St. Paul School (K-12 population 88 students), the elementary classes in 2011 were K-1, 2-3-4, 5-6, while in 2012 the elementary classes were K, 1-2-3, 4-5, 6. In small schools with multi-grade classes, it is more flexible to have teachers conduct short-term evaluation of results rather than to have a program-developed assessment. AFSC educators will work closely with Pribilof School District educators to develop a long-term evaluation plan to track knowledge retention of students from one year to the next.

What is your current job title?

What is your current job title?